Wake Turbulence

Wake Turbulence is a disturbance created by aircraft (lift) that can produce undesirable flight characteristics to any who encounters the wake.

Introduction to Wake Turbulence

- Every aircraft generates a wake while in flight.

- Wake turbulence is a function of an aircraft producing lift, creating a vortex that forms two counter-rotating vortices trailing behind the aircraft.

- Wake turbulence from the generating aircraft can affect encountering aircraft due to the strength and behavior of the vortices.

- Vortices can impose rolling moments that exceed the roll-control authority of the encountering aircraft, potentially causing injury to occupants and damage to the aircraft.

- In a slow hover taxi or stationary hover near the surface, the helicopter's main rotor(s) generate downwash, producing high velocity outwash vortices to a distance approximately three times the diameter of the rotor.

- Pilots must learn to envision the location of the vortex wake generated by larger aircraft and adjust the flight path accordingly.

Vortex Formation

- The creation of a pressure differential over the wing surface generates lift.

- The lowest pressure occurs over the upper wing surface, and the highest pressure occurs under the wing.

- This pressure differential triggers the roll-up of the airflow at the rear of the wing, resulting in swirling air masses trailing downstream of the wingtips.

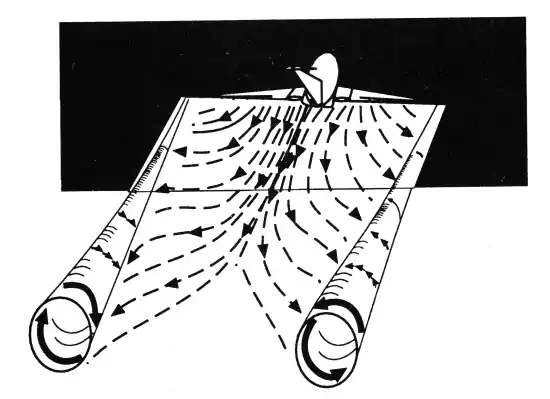

- After the roll-up, the wake consists of two counter-rotating cylindrical vortices. [Figure 1]

- The wake vortex forms with most of the energy concentrated within a few feet of the vortex core.

- Most of the energy is within a few feet of the center of each vortex, but pilots should avoid a region within about 100' of the vortex core.

- More aircraft are being manufactured or retrofitted with winglets to increase fuel efficiency (by improving the lift-to-drag ratio).

- Studies have shown, however, that winglets have a negligible effect on wake turbulence generation, particularly with the slower speeds involved during departures and arrivals.

-

Vortex Strength:

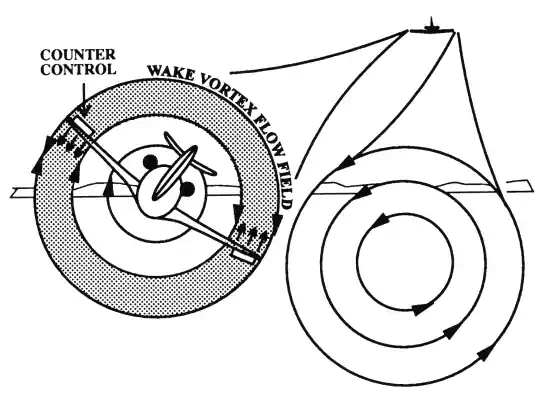

- The strength of the vortex depends on the weight, speed, wingspan, and shape of the generating aircraft's wing. [Figure 2]

- The vortex strength from an aircraft increases proportionately to an increase in operating weight or a decrease in aircraft speed.

- Characteristics change with the extension of flaps or other wing-configuring devices.

- Peak vortex tangential speeds have been exceeding 300' per second.

- An aircraft creates the greatest vortex strength when:

- Heavy.

- Clean.

- Slow.

- High wing loading amplifies the effects of vortex strength.

- Except for when landing gear and flaps are down, which actually tend to disrupt wake turbulence, you can see that it is primarily the terminal area, when you are low to the ground, that you may expect to see this phenomenon.

Induced Roll:

- In rare instances, a wake encounter could cause catastrophic in-flight structural damage to an aircraft.

- However, the usual hazard is associated with induced rolling moments that can exceed the roll-control authority of the encountering aircraft.

- Induced roll is especially dangerous during takeoff and landing when there is little altitude for recovery.

- During in-flight testing, the aircraft intentionally flew directly through the trailing vortex cores of larger aircraft.

- These tests demonstrated that the ability of aircraft to counteract the roll imposed by wake vortex depends primarily on the wingspan and counter-control responsiveness of the encountering aircraft.

- These tests also demonstrated the difficulty for an aircraft to remain within a wake vortex.

- The natural tendency is for the circulation to eject aircraft from the vortex.

- Counter-control is usually effective and induces minimal roll in cases where the wingspan and ailerons of the encountering aircraft extend beyond the rotational flow field of the vortex.

- It is more difficult for aircraft with a short wingspan (relative to the generating aircraft) to counter the imposed roll induced by vortex flow.

- The wake of larger aircraft requires the respect of all pilots.

- Pilots of short-span aircraft, even of the high-performance type, must be especially alert to vortex encounters.

- In rare instances, a wake encounter could cause catastrophic in-flight structural damage to an aircraft.

- The strength of the vortex depends on the weight, speed, wingspan, and shape of the generating aircraft's wing. [Figure 2]

Vortex Behavior

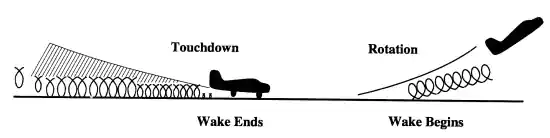

- Vortices begin to form from the moment the aircraft leaves the ground as a byproduct of lift. [Figure 3]

- Before takeoff or touchdown, pilots should note the rotation or touchdown point of the preceding aircraft.

- Circulation is outward, upward, and around the wing tips.

- Vortices remain spaced less than a wingspan apart, drifting with the wind at altitudes greater than a wingspan above the ground.

- Given this, if encountering persistent vortex turbulence, a slight change of altitude (upward) and lateral position (upwind) should provide a flight path clear of the turbulence.

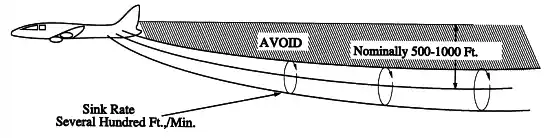

- Those from larger aircraft sink at a rate of several hundred feet per minute, slowing their descent and diminishing in strength with time and distance behind the generating aircraft. [Figure 4]

- When present, atmospheric turbulence hastens breakup.

- Pilots should fly at or above the preceding aircraft's flight path, altering course as necessary to avoid the area directly behind and below the generating aircraft.

- However, vertical separation of 1,000 feet may be considered safe.

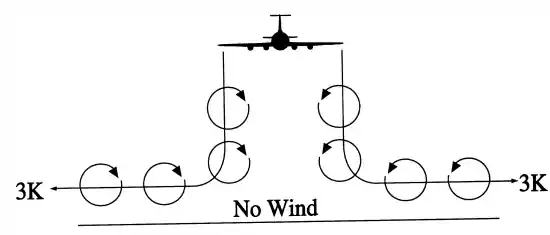

- When vortices sink close to the ground (within 1-200'), they tend to move laterally over the ground at a speed of 2 or 3 knots. [Figure 5/6/7]

- Pilots should remain alert at all times for possible wake vortex encounters during approach and landing operations.

- The pilot is ultimately responsible for maintaining an appropriate interval and should consider all available information in positioning the aircraft in the terminal area to avoid the wake turbulence created by a preceding aircraft.

- Test data show that vortices can rise with the air mass that contains them.

- The effects of wind shear can cause a vortex flow field "tilting."

- In addition, ambient thermal lifting, orographic effects (such as rising terrain or tree lines), can cause a vortex flow field to rise and possibly bounce.

- A crosswind will decrease the lateral movement of the upwind vortex and increase the movement of the downwind vortex.

- Thus, a light wind with a cross-runway component of 1 to 5 knots could result in the upwind vortex remaining in the touchdown zone for some time and hasten the drift of the downwind vortex toward another runway.

- A tailwind condition can cause the vortices to move forward into the touchdown zone.

- The light quartering tailwind requires maximum caution.

-

Operations Problem Areas:

- The probability of induced roll increases when the encountering aircraft's heading generally aligns with the flight path of the generating aircraft.

- A crosswind will decrease the lateral movement of the upwind vortex and increase the movement of the downwind vortex.

- Thus, a light wind with a cross runway component of 1 to 5 knots could result in the upwind vortex remaining in the touchdown zone for a period of time and hasten the drift of the downwind vortex toward another runway.

- Similarly, a tailwind condition can cause the vortices of the preceding aircraft to move forward into the touchdown zone.

- THE LIGHT QUARTERING TAILWIND REQUIRES MAXIMUM CAUTION.

- Pilots should be alert to large aircraft upwind from their approach and takeoff flight paths.

- Pilots should be vigilant in calm wind conditions and situations where the vortices could:

- Remain in the touchdown area.

- Drift from aircraft operating on a nearby runway.

- Sink into the takeoff or landing path from a crossing runway.

- Sink into the traffic pattern from other airport operations.

- Sink into the flight path of VFR aircraft operating on the hemispheric altitude 500' below.

- AVOID THE AREA BELOW AND BEHIND THE GENERATING AIRCRAFT, ESPECIALLY AT LOW ALTITUDES, WHERE EVEN A MOMENTARY WAKE ENCOUNTER COULD BE HAZARDOUS.

Avoidance Procedures

- Under certain conditions, airport traffic controllers apply procedures for separating IFR aircraft.

- If a pilot accepts a clearance to follow a preceding aircraft visually, they accept responsibility for ensuring separation and avoiding wake turbulence.

- The controllers will also provide to VFR aircraft, with whom they are in communication and which, in the tower's opinion, may be adversely affected by wake turbulence from a larger aircraft, the position, altitude, and direction of flight of larger aircraft, followed by the phrase "caution, wake turbulence."

- After being told "caution, wake turbulence," the controller generally does not provide additional information.

- Whether or not given a warning or information, the expectation is that the pilot adjusts aircraft operations and flight path as necessary to preclude serious wake encounters.

- When in doubt, ask.

-

Landing behind a larger aircraft - same runway:

- Stay at or above the larger aircraft's final approach flight path, note its touchdown point, and land beyond it.

- Incident data shows that the most significant potential for a wake vortex incident occurs when a light aircraft is turning from base to final behind a heavy aircraft flying a straight-in approach.

- Use extreme caution to intercept the final above or well behind the heavier aircraft.

- When a pilot accepts a visual approach to follow a preceding aircraft, the pilot must establish a safe landing interval behind the instructed aircraft.

- Pilots must not decrease the separation that existed when the visual approach was issued unless they can remain on or above the flight path of the preceding aircraft.

- Stay at or above the larger aircraft's final approach flight path, note its touchdown point, and land beyond it.

-

Landing behind a larger aircraft - when a parallel runway is closer than 2,500':

- Consider the possible drift to your runway.

- Stay at or above the larger aircraft's final approach flight path- note its touchdown point.

-

Landing behind a larger aircraft - crossing runway:

- Cross above the larger aircraft's flight path.

-

Landing behind a departing larger aircraft - same runway:

- Note the larger aircraft's rotation point, and land well before it.

-

Landing behind a departing larger aircraft - crossing runway:

- Note the larger aircraft's rotation point, and if past the intersection, continue the approach to land before the intersection.

- If a larger aircraft rotates before the intersection, avoid flight below the larger aircraft's flight path.

- Abandon the approach unless a landing is ensured well before reaching the intersection.

-

Departing behind a larger aircraft:

- Note the larger aircraft's rotation point and rotate before it.

- Continue climbing above the larger aircraft's climb path until turning clear of the larger aircraft's wake.

- Avoid subsequent headings that will cross below and behind a larger aircraft.

- Be alert for any critical takeoff situation that could lead to a vortex encounter.

-

Intersection takeoffs - same runway:

- Be alert to the operations of adjacent larger aircraft, particularly those upwind of your runway.

- If intersection takeoff clearance is received, avoid subsequent headings that will cross below a larger aircraft's path.

-

Departing or landing after a larger aircraft executing a low approach, missed approach, or touch-and-go landing:

- Because vortices settle and move laterally near the ground, the vortex hazard may exist along the runway and in your flight path after a larger aircraft has executed a low approach, missed approach, or a touch-and-go landing, particularly in light quartering wind conditions.

- If you can, climb above the preceding aircraft's flight path.

- If you can't outclimb it, deviate slightly upwind and climb parallel to the prior aircraft's course.

- Avoid headings that cause you to cross behind and below the preceding aircraft.

- Ensure that an interval of at least 2 minutes has elapsed before taking off or landing.

-

En route VFR (thousand-foot altitude plus 500'):

- Avoid flying below and behind a large aircraft's path.

- If you must cross under, do so at least 1000' below.

- If a larger aircraft is observed above on the same track (meeting or overtaking), adjust your position laterally, preferably upwind.

- Guidance on Wake Turbulence:

Pilot Action to Mitigate Wake Turbulence Encounters:

Pilots should be alert for wake turbulence when operating:

- In the vicinity of aircraft climbing or descending through their altitude.

- Approximately 10-30 miles after passing 1,000' below opposite-direction traffic.

- Approximately 10-30 miles behind and 1,000' below same-direction traffic.

- Pilots encountering or anticipating wake turbulence in DRVSM airspace have the option of requesting a vector, FL change, or, if capable, a lateral offset.

- Offsets of approximately a wing span upwind generally can move the aircraft out of the immediate vicinity of another aircraft's wake vortex.

- In domestic U.S. airspace, pilots must request clearance to fly a lateral offset. Strategic lateral offsets flown in oceanic airspace do not apply.

Warning Signs

- Wakes may cause uncommanded aircraft movements (i.e., wing rocking).

- Maintaining situational awareness is so critical. Ordinary turbulence is not unusual, particularly in the approach phase.

- A pilot who suspects wake turbulence is affecting their aircraft should get away from the wake, execute a missed approach or go-around, and be prepared for a stronger wake encounter.

- The onset of wake can be insidious and even surprisingly gentle.

- There have been serious accidents where pilots have attempted to salvage a landing after encountering moderate wake, only to encounter severe wake vortices.

- Pilots should not rely solely on aerodynamic warnings; they should perform immediate evasive action if wake onset occurs.

Helicopter Specifics

- While the behavioral characteristics are similar to a fixed-wing aircraft, circulation is outward, upward, around, and away from the main rotor(s) in all directions.

- In fact, helicopter wakes may be of significantly greater strength than those from a fixed-wing aircraft of the same weight.

- Pilots of small aircraft should avoid operating within three rotor diameters of any helicopter in a slow hover taxi or stationary hover.

- In forward flight, departing or landing helicopters produce a pair of strong, high-speed trailing vortices, similar to those made by fixed-wing aircraft.

- The strongest wake can occur when the helicopter is operating at lower speeds (20 - 50 knots).

- Some mid-size or executive-class helicopters produce wake as strong as that of heavier helicopters.

- Two-blade main rotor systems, typical of lighter helicopters, produce stronger wakes than rotor systems with more blades.

- Pilots of small aircraft should use caution when operating behind or crossing behind landing and departing helicopters.

Wake Turbulence Responsibilities

-

Pilot Responsibilities:

- Although ATC is there to help, the flight disciplines necessary to ensure vortex avoidance during VFR operations must be exercised by the pilot, especially when operating under VFR conditions.

- When operating behind any aircraft, pilots acknowledge responsibility for ensuring safe takeoff and landing intervals and providing wake turbulence separation by accepting ATC instructions in the following situations.

- Traffic information.

- Instructions to follow an aircraft.

- The acceptance of a visual approach clearance.

- ATC will specify the word "super" or "heavy" as appropriate for operations conducted behind super or heavy aircraft when this information is known. Pilots of super or heavy aircraft should always use the word "super" or "heavy" in radio communications.

- Super, heavy, and large jet aircraft operators should follow the procedures outlined below during an approach to landing. These procedures establish a dependable baseline from which pilots of in-trail, lighter aircraft may reasonably expect to make effective flight path adjustments to avoid severe wake vortex turbulence.

- Pilots of aircraft that produce strong wake vortices should make every attempt to fly on the established glide-path, not above it; or, if glide-path guidance is not available, to fly as closely as possible to a "3-1" glide-path, not above it.

- Fly 3,000' at 10 miles from touchdown, 1,500' at 5 miles, 1,200' at 4 miles, and so on to touchdown.

- Pilots of aircraft that produce strong wake vortices should make every attempt to fly on the established glide-path, not above it; or, if glide-path guidance is not available, to fly as closely as possible to a "3-1" glide-path, not above it.

- Pilots of aircraft that produce strong wake vortices should fly as closely as possible to the approach course centerline or to the extended centerline of the runway of intended landing, as appropriate to conditions.

- Pilots operating lighter aircraft on visual approaches in-trail to aircraft producing strong wake vortices should use the following procedures to avoid wake turbulence. These procedures apply only to aircraft on visual approaches.

- Pilots of lighter aircraft should fly on or above the glide path. An ILS may furnish glide-path reference, a visual approach slope system, other ground-based approach slope guidance systems, or other means. In the absence of visible glide-path guidance, pilots may very nearly duplicate a 3-degree glide-slope by adhering to the "3 to 1" glide-path principle.

- Fly 3,000' at 10 miles from touchdown, 1,500' at 5 miles, 1,200' at 4 miles, and so on to touchdown.

- If the pilot of the lighter, following aircraft, has visual contact with the preceding heavier aircraft and also with the runway, the pilot may further adjust for possible wake vortex turbulence by following these practices:

- Pick a point of landing no less than 1,000' from the arrival end of the runway.

- Establish a line-of-sight to that landing point that is above and in front of the heavier preceding aircraft.

- Note the point of landing of the heavier preceding aircraft and adjust the point of intended landing as necessary.

- A puff of smoke may appear at 1,000' markings of the runway, indicating that touchdown occurred at that point; therefore, adjust the point of intended landing to the 1,500' markings.

- Maintain a line of sight to the point of intended landing above and ahead of the heavier preceding aircraft; maintain it until touchdown.

- Land beyond the point of landing of the preceding heavier aircraft, ensuring you have adequate runway remaining if conducting a touch-and-go landing, or adequate stopping distance available for a full-stop landing.

- During visual approaches, pilots may request updates from ATC on separation and ground speed with respect to heavier preceding aircraft, especially when there is any question of maintaining safe separation from wake turbulence.

- Pilots should notify ATC when they encounter a wake event.

- Be as descriptive as possible (i.e., bank angle, altitude deviations, intensity and duration of the event, etc.) when reporting the event.

- ATC will record the event through their reporting system. You are also encouraged to use the Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) to report wake events.

- Pilots may, if desired, waive separation due to wake turbulence by explicitly requesting one.

- If doing so, pilots are assuming the risk.

- Pilots should not waive separation for convenience unless they determine it is safe to do so.

- Pilots of lighter aircraft should fly on or above the glide path. An ILS may furnish glide-path reference, a visual approach slope system, other ground-based approach slope guidance systems, or other means. In the absence of visible glide-path guidance, pilots may very nearly duplicate a 3-degree glide-slope by adhering to the "3 to 1" glide-path principle.

-

Controller Responsibilities:

- Controllers, while providing radar vector service, are responsible for applying the wake-turbulence longitudinal separation distances between IFR aircraft and wake-turbulence advisories to VFR aircraft.

- Air traffic controllers are responsible for providing cautionary wake turbulence information to assist pilots in avoiding it before they assume visual flight rules (VFR) responsibilities.

- Controllers must issue wake-turbulence cautionary advisories and the position, altitude, if known, and direction of flight of heavy jets or B-757s to:

- VFR aircraft not under radar vectored, but are behind heavy jets or B757s.

- VFR arriving aircraft that have previously been radar vectored are no longer.

- IFR aircraft that accept a visual approach or visual separation.

- Air traffic controllers should also issue cautionary information to any aircraft if, in their opinion, wake turbulence may adversely affect it.

- Tower controllers are responsible for runway separation for aircraft arriving or departing the airport.

- Tower controllers do not provide visual wake turbulence separation to arriving aircraft; that is the pilot's responsibility.

- Air traffic controllers are responsible for applying the appropriate wake turbulence separation criteria for departing aircraft.

Wake Turbulence Separation

- Because of the possible effects of wake turbulence, controllers apply no less than the minimum required separation to all aircraft operating behind a "Super" or "Heavy," and to Small aircraft operating behind a B757, when aircraft are IFR, VFR, and receiving Class B, Class C, or TRSA airspace services; or VFR and being radar sequenced.

- Separation is applied to aircraft operating directly behind a super or heavy at the same altitude or less than 1,000 feet below, and to small aircraft operating directly behind a B757 at the same altitude or less than 500 feet below:

- Heavy behind super: 6 miles.

- Large behind super: 7 miles.

- Small behind super: 8 miles.

- Heavy behind heavy: 4 miles.

- Small/large behind heavy: 5 miles.

- Small behind B757: 4 miles.

- Also, separation, measured at the time the preceding aircraft is over the landing threshold, is provided to small aircraft:

- Small landing behind heavy - 6 miles.

- Small landing behind large, non-B757 - 4 miles.

- Separation is applied to aircraft operating directly behind a super or heavy at the same altitude or less than 1,000 feet below, and to small aircraft operating directly behind a B757 at the same altitude or less than 500 feet below:

- Additionally, appropriate time or distance intervals are provided to departing aircraft when the departure will be from the same threshold, a parallel runway separated by less than 2,500 feet with less than 500 feet threshold stagger, or on a crossing runway, and projected flight paths will cross:

- Three minutes or the appropriate radar separation when taking off will be behind a super aircraft.

- Two minutes or the appropriate radar separation is required when taking off behind a heavy aircraft.

- Two minutes or the appropriate radar separation when a small aircraft will take off behind a B757.

- NOTE: Controllers may not reduce or waive these intervals.

- A 3-minute interval is applied when a small aircraft takes off:

- From an intersection on the same runway (same or opposite direction) behind a departing B757, or.

- In the opposite direction on the same runway behind a B757 takeoff or low/missed approach.

- NOTE: ATC is not to waive the 3-minute interval, even at the pilot's request.

- Controllers apply a 4-minute interval for all aircraft taking off behind a super aircraft, and a 3-minute interval for all aircraft taking off behind a heavy aircraft when the operations are as described above, assuming operations are on the same or parallel runways separated by less than 2,500 feet. Controllers may not reduce or waive this interval.

- Pilots may request additional separation (i.e., 2 minutes instead of 4 or 5 miles) for wake turbulence avoidance. Make the request as soon as practical on ground control and at least before taxiing onto the runway.

- NOTE: 14 CFR Section 91.3(a) states: "The pilot-in-command of an aircraft is directly responsible for and is the final authority as to the operation of that aircraft."

- Controllers may anticipate separation and do not need to withhold a takeoff clearance for an aircraft departing behind a large, heavy, or super aircraft if there is reasonable assurance that the required separation will exist when the departing aircraft begins its takeoff roll.

- With the advent of new wake turbulence separation methodologies, known as Wake Turbulence Recategorization, some of the requirements listed above may vary at facilities authorized to operate in accordance with Wake Turbulence Recategorization directives.

- Note that, ultimately, when operating under VFR, it is the pilot's responsibility, not ATC's, to provide this separation.

Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum (RVSM) Considerations

- Wake turbulence can still exist at RVSM altitudes, but will generally be moderate or less in magnitude.

- Pilots should remain alert when operating:

- In the vicinity of aircraft climbing or descending through their altitude.

- Approximately 10-30 miles after passing 1,000' below the opposite direction traffic.

- Approximately 10-30 miles behind and 1,000' below the same direction traffic.

- Pilots may request a vector or a different altitude if they believe they are at risk of encountering wake turbulence.

- Before the implementation of DRVSM, the FAA established provisions for pilots to report wake turbulence events in RVSM airspace using the NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS). A "Safety Reporting" section has been established on the FAA RVSM Documentation webpage, providing contacts, forms, and reporting procedures.

- To date, wake turbulence is not a significant factor in DRVSM operations. European authorities also found that reports of wake turbulence encounters did not increase significantly after RVSM implementation (eight versus seven reports in the ten months following implementation). In addition, they found that reported wake turbulence was generally similar to moderate clear air turbulence.

- Report wake turbulence events using the NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) on the FAA RVSM Documentation web page under Safety Reporting.

Wake Turbulence Lessons & Case Studies

- Some accidents have occurred even though the pilot of the trailing aircraft had carefully noted that the aircraft in front was at a considerably lower altitude. Unfortunately, this does not ensure that the flight path of the lead aircraft will be below that of the trailing aircraft.

- A wake encounter can be catastrophic. In 1972, at Fort Worth, a DC-9 got too close to a DC-10 (two miles back), rolled, caught a wingtip, and cartwheeled, coming to rest in an inverted position on the runway, killing all on board. Serious and even fatal GA accidents induced by wake vortices are not uncommon. However, a wake encounter is not necessarily hazardous. It can be one or more jolts with varying severity depending upon the direction of the encounter, the generating aircraft's weight, the encountering aircraft's size, distance from the generating aircraft, and the point of vortex encounter. The probability of induced roll increases when the encountering aircraft's heading aligns with the flight path of the generating aircraft.

- A typical scenario for a wake encounter is in terminal airspace after accepting clearance for a visual approach behind landing traffic. Pilots must be aware of their position relative to the traffic and use all means of vertical guidance to ensure they do not fly below the flight path of the wake-generating aircraft.

Wake Turbulence Conclusion

- Aircraft may encounter wake turbulence both in flight and while operating in the airport movement area.

- A wake turbulence encounter can range from negligible to catastrophic.

- The impact of the encounter depends on several factors, including the weight, wingspan, and size of the generating aircraft, as well as the distance from the generating aircraft and the point of vortex encounter.

- Pilots, in all phases of flight, must remain vigilant of possible wake effects created by other aircraft.

- Studies have shown that atmospheric turbulence hastens wake breakup, while other atmospheric conditions can transport the wake horizontally and vertically.

- While ATC has required warnings that they must provide, the pilot has the ultimate responsibility for ensuring that appropriate separations and positioning of the aircraft in the terminal area are maintained to avoid the wake turbulence created by a preceding aircraft.

- Offsets of approximately a wing span upwind generally can move the aircraft out of the immediate vicinity of another aircraft's wake vortex.

- In domestic U.S. airspace, pilots must request clearance to fly a lateral offset. Strategic lateral offsets flown in oceanic airspace do not apply.

- Your most significant hazard from wake turbulence will be induced roll.

- In rare instances, a wake encounter could cause in-flight structural damage of catastrophic proportions.

- Pilots should attempt to visualize the vortex trail of aircraft whose projected flight path they may encounter. When possible, pilots of larger aircraft should adjust their flight paths to minimize the exposure of other aircraft to vortices.

- If unable, or to increase the safety margin, allowing time for the vortex to dissipate reduces risk.

- While it may be ATC's job, it is the pilot's responsibility for wake turbulence separation as Pilot-In-Command.

- Recognize that every single aircraft generates wake turbulence.

- Remember, the effects of wake turbulence will vary based on the big three: heavy, clean, and slow.

- Based on extensive analysis of wake vortex behavior, new procedures and separation standards are being developed and implemented in the U.S. and throughout the world.

- Wake research involves both the wake-generating aircraft and the wake tolerance of the trailing aircraft.

- The FAA and ICAO are leading initiatives in terminal environments to implement these next-generation wake turbulence procedures and separation standards.

- The FAA has undertaken an effort to recategorize the existing fleet of aircraft and modify associated wake turbulence separation minima. This initiative is known as Wake Turbulence Recategorization (RECAT). It replaces the current weight-based classes (Super, Heavy, B757, Large, Small+, and Small) with a wake-based categorical system that utilizes the aircraft's matrices of weight, wingspan, and approach speed. RECAT is currently in use at a limited number of airports in the National Airspace System.

- Terms like super, heavy, and large are in the Pilot/Controller Glossary Term - Aircraft Classes.

- See also: Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS).

- Still looking for something? Continue searching:

Wake Turbulence References

- Advisory Circular (90-23G) Aircraft Wake Turbulence.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (4-6-7) Guidance on Wake Turbulence.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-4-1) General.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-4-2) Vortex Generation.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-4-3) Vortex Strength.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-4-4) Vortex Behavior.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-4-5) Operations Problem Areas.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-4-6) Vortex Avoidance Procedures.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-4-7) Helicopters.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-4-8) Pilot Responsibility.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-4-9) Air Traffic Wake Turbulence Separations.

- Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association - FAA Seeks Wake Turbulence Encounter Reports.

- Federal Aviation Administration - Pilot and Air Traffic Controller Guide to Wake Turbulence.

- Federal Aviation Administration - Pilot/Controller Glossary.

- Federal Aviation Administration Order (JO 7110.659) Wake Turbulence Recategorization.

- Federal Aviation Administration Order (JO 7110.123) Wake Turbulence Recategorization - Phase II.

- Federal Aviation Administration Order (JO 7110.126) Consolidated Wake Turbulence.

- Pilot/Controller Glossary Term - Aircraft Classes.

- Pilot Workshops - Wake Turbulence?.