Maneuvers & Procedures

Much of aviation is procedural, requiring pilots to know and practice all maneuvers related to their aircraft operation.

Introduction

- Every maneuver has a purpose, so it is equally important to understand why and not just how.

- Maneuvers are diverse, and the applicability of many depends on your operation; however, they always follow a general pattern.

- Ground operations proceed with all flight operations, the careful observance of which sets the stage for an entire flight.

- Once ready, pilots execute takeoff procedures and transition to the enroute environment.

- While airborne, pilots may elect to practice maneuvers to hone their skills.

- These include ground reference maneuvers and other airborne maneuvers, stalls, formation flight, and even aerobatics.

- A dedicated set of instrument procedures procedures applies to operations within instrument meteorological conditions.

- Once complete, pilots return to the terminal area to complete the approach and landing procedures.

- Not every flight will be perfect, and emergencies may arise that require immediate pilot intervention.

Ground Operations

- All flights start and end with ground operations.

- Pilots determine airworthiness, starting with a thorough preflight to proceed with the flight.

- With a determination made, pilots conduct starting procedures to verify the operation of the powerplant and aircraft systems.

- With ground checks nearly complete, pilots must taxi across the airport surface area to conduct the run-up and prepare for takeoff.

- As mentioned, all flights will end with ground operations, necessitating a specified set of post-flight procedures.

Takeoff & Landing

- Takeoffs and landings are straightforward concepts, but their execution under various conditions can make them complex.

- Depending on wind direction, runway alignment, and other variables, pilots may be required to execute different takeoff maneuvers to get airborne and recover safely.

-

Takeoffs and Climbs:

- Takeoffs and climbs transition the pilot and aircraft from the ground to the flight environment.

- However, not all takeoffs are equal, as the environment and terminal area may require specific considerations.

- Although conditions rarely favor using a Normal Takeoff and Climb, the procedures provide a baseline.

- One such example is variable wind direction relative to a static runway direction.

- Despite some airports having several runways aligned to the prevailing winds, the wind is rarely straight down the runway, which requires pilots to execute Crosswind Takeoff and Climb procedures.

- Shorter, often remote airfields require Short Field Takeoff and Climb procedures to remain within the aircraft's limitations while pushing spacial limitations.

- Unimproved airfields require Soft Field Takeoff and Climb procedures to mitigate the ground conditions.

-

Approach and Landings:

- Under some conditions, a Normal Approach and Landing may suffice.

- As with takeoff, however, conditions will vary, which may call for using a Crosswind Approach and Landing to compensate for winds.

- Short Field Approach and Landing procedures allow pilots to maximize energy management to land the aircraft in the minimum space.

- Unprepared surfaces carry special considerations necessitating a Soft Field Approach and Landing procedures to mitigate.

- A stabilized approach is the key to a good landing, regardless of the procedure flown.

- When pilots fail to establish a stabilized approach or an unexpected condition develops, like a fouled runway, pilots execute the rejected landing/go-around

- Approaches to landing are all based in the principles of energy management.

- Applying the principles learned in the different approaches to landing procedures, pilots must demonstrate no-flap approach and landings, with the most advanced pilots demonstrating power-off 180 approach and landing proficiency.

- The no-flap and power-off-180 approach and landing require pilot judgment based on standard procedures flown under non-standard circumstances.

-

Traffic Pattern Operations:

- Pilots practice takeoffs and landings by conducting touch and go operations

- Standardized procedures allow pilots to train in the statistically most dangerous and challenging phase of flight.

Ground Reference Maneuvers

- Ground reference maneuvers and their related objectives develop a high degree of pilot skill.

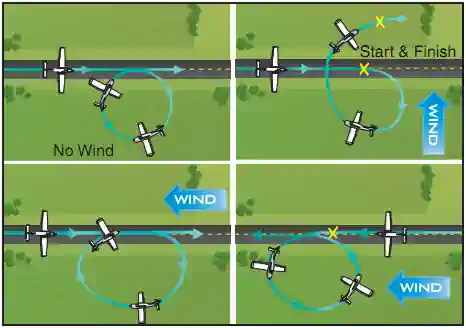

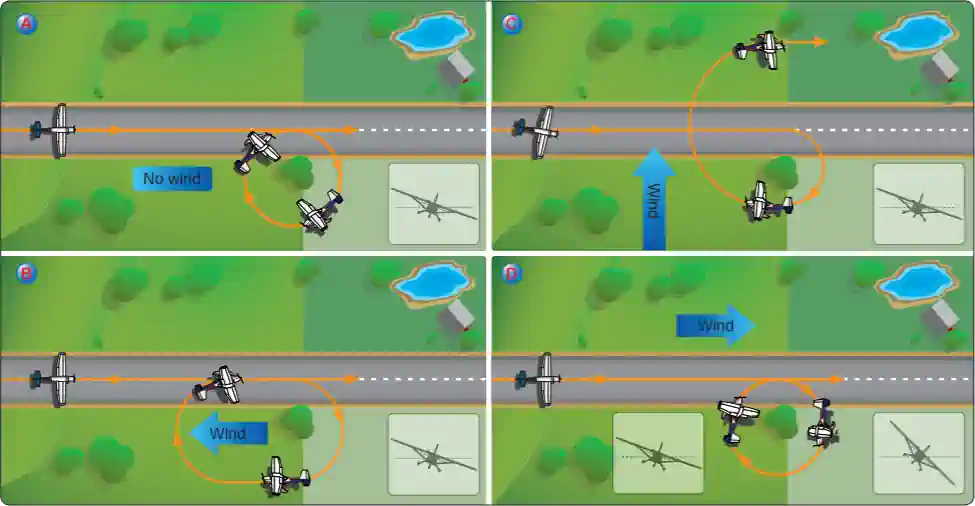

- Wind direction and velocity variations are the primary effects requiring flight path corrections during ground reference maneuvers. [Figure 1]

- Like a boat, wind directly influences the path the airplane travels about the ground.

- Whenever the aircraft is in flight, the movement of the air directly affects the aircraft's actual ground track.

- Although few perform ground reference maneuvers regularly, the elements and principles involved in each apply to many operations.

- They aid the pilot in analyzing the effect of wind and other forces acting on the airplane and developing a delicate control touch, coordination, and the division of attention necessary for accurate and safe airplane maneuvering.

-

Maneuvering by Reference to Ground Objects:

- Ground track or ground reference maneuvers are performed at a relatively low altitude while applying wind drift correction to follow a predetermined track or path over the ground.

- Ground reference maneuvers are generally flown at approximately 600 to 1,000' AGL, depending on the speed and type of airplane to a large extent.

- Consider the following:

- Drift should be easily discernible but not taxing the pilot to make corrections.

- Objects on the ground should appear in their proportion and size.

- The altitude should be low enough to make any gain or loss apparent to the student, but it should not be lower than 500' above the highest obstruction.

- During ground reference maneuvers, the instructor and the student should be alert for available forced-landing fields.

- The area chosen should be away from communities, livestock, and groups of people to prevent possible annoyance or hazards.

- The low maneuvering altitudes limit the time available to search for a suitable field for landing if the need arises.

-

Ground Reference Maneuver Procedures:

- To perform any ground reference maneuvers, the pilot must be familiar with the effects of wind drift

- Next, pilots will take these lessons learned to perform turns around a point and eventually s-turns accurately.

- These maneuvers build to the rectangular course,, preparing pilots to fly the traffic pattern to practice takeoffs and landings.

- "Eights" demonstrate the interactions between maneuvers while developing a pilot's fine motor skills for turns and altitude changes about a known point:

- Eights along a road develops the ability to maneuver the airplane accurately while dividing your attention between the flight path and the selected points on the ground.

- Eights across a road continues building the skills associated with eights along a road but adds precision as the airplane should cross an intersection of roads or a specific point on a straight road.

- Eights around pylons adds the requirement for moderate to steep turns.

- Eights on pylons completes the series by perfecting the knowledge of the effect of the angle of bank on the radius of turn and adding a vertical dimension as the pivotal altitude.

Cruise/Airborne Maneuvers

- Cruise starts with performing Straight-and-Level Flight, which, while less dynamic than the terminal phases of flight, requires a unique set of skills to manage efficiently.

- Turn procedures introduce a lateral dimension to straight and level flight that demonstrates the complicated interaction of forces on an aircraft.

- Maneuvering during slow flight allows pilots to feel the performance associated with minimum controllable airspeed and the margins that can lead to a stall, especially in turn.

- While turns illustrate the dynamic forces acting upon an aircraft, steep turns take those forces to the next level.

- Unusual Attitudes.

- In all phases of flight across climbs, descents, airspeed changes, etc., pilots must practice trimming the aircraft, removing control pressures, reducing pilot workload, and improving the smoothness of flight.

Commercial Certificate Maneuvers

Leaning Procedures

- Ground (high elevation):

- Ensure the mixture control is full forward (full rich).

- Lean the mixture by slowly moving the Mixture control back to the stop, but only enough to obtain smooth operation.

- Climb:

- Leave the mixture control in the full forward (full rich) position.

- As you climb (above 3000 ft Density Altitude in many trainers), leaning will improve engine performance.

- Cruise:

- Slowly move the mixture control back until noting a slight increase in airspeed and engine operation becomes rough.

- If the engine operation is rough, slowly move the mixture control forward to obtain smooth engine operation.

- If an Exhaust Gas Temperature (EGT) gauge is available, lean to peak (best power).

- Note that the best power does not account for climbs/descents.

- Rich of peak provides the best economy.

- Ground Reference Maneuvers:

- Ensure the mixture is fully forward (fully rich) and the electric fuel pump (if equipped) is off.

- Other Maneuvers:

- Leave the mixture control in the leaned position, and the electric fuel pump (if equipped) is off.

- Descent:

- Slowly move the mixture control forward to enrich the mixture during descent.

- Landing:

- Slowly move the mixture control to the full forward (full rich) position.

- Turn the electric fuel pump on when descending through 1000 feet AGL.

Aerobatics

- Aerobatics, not to be confused with acrobatics, tests a pilots precision and performance skills and knowledge

- Maneuvers include:

Instrument Rating Maneuvers and Procedures

Stalls

- Stalls in aviation refer to the separation of airflow over the wings after the wing reaches the Critical Angle of Attack (AoA)

- The critical AoA is the AOA when reached, results in a stall

- Stalls can occur at any airspeed, at any flight attitude, or at any weight, as they are completely dependent on the AoA

-

Stall Recognition:

- Several methods are available to recognize stalls:

- Vision: noting the attitude of the airplane, however, not conducive to recognizing approaching stalls

- Hearing: RPM loss, more airflow noise around the cabin

- Kinesthesia: sensing in directions or speed of motion, which is the most important indicator you have

- Feel: control pressures and pressures exerted

- Aircraft Warnings: horns, rudder shakers, stick shakers

- Several methods are available to recognize stalls:

-

Stall Recovery:

- Reduce AoA!

- Reducing AoA is the only way to start the recovery process and may be done by lowering the nose or increasing power, however in most aircraft, lowering the nose is the only logical step you have

- Increase airspeed (lift)

- Maintain coordinated use of controls

- Reduce AoA!

-

Types of Stalls:

- Power-on (departure) stalls simulate insufficient airflow over the wing while configured for and flying the departure phase of flight

- Power-off (approach) stalls are the opposite of power-on stalls, simulating insufficient airflow over the wing while configured for and flying the approach phase of flight

- Related to stalling on approach is the risk of stalling when a go-around is initiated while the aircraft is configured for landing

- Elevator trim stall therefore simulate the rapid increase of power applied to an aircraft trimmed to favor/maintain a nose-up attitude, thereby stalling the aircraft on when going around

- Accelerated stalls can occur when the aircraft is under load, such as in a turn or high-performance maneuver that has the wing under load

- Recoveries are by their nature flown at operational limitations, but overly aggressive or improperly flown stall recoveries can lead into secondary stalls exacerbating the stall by stalling again

- In any case, stalling while not in coordinated flight risks a cross-control stall, leading to not only a loss of alttiude, but increased risk of a spin

Emergency

- When an emergency occurs, the pilot must remember to aviate, navigate, and communicate in that order

- Maintain aircraft control

- Analyze the situation and take corrective action

- Land as soon as possible/practicable

- The Pilot-in-Command during an emergency is the final authority

- This authority applies to extenuating circumstances

- Procedures, as written, are that way for a reason, and pilots should not blindly deviate without considering the entirety of the situation

- Steep Spirals

- Emergency Approach and Landing

- Spins

- Ditching

Formation

- Formation flights are efficient and expeditious ways of moving multiple aircraft in an orderly fashion, typically used by the military

- Formation flight can be the most challenging and rewarding experience in aviation, but it is not without its dangers

Control Transfer Procedures

- When transferring controls from one pilot to another, it is critical to be assertive and conscious of good Crew Resource Management practices

- Transfer controls using a "positive three-way" method:

- Pilot flying states, "You have the controls"

- The pilot flying continues to positively control the aircraft

- Pilot not flying states, "I have the controls"

- The pilot not flying puts their hands on the controls but is not yet the pilot flying

- The original pilot flying states, "You have the controls"

- At this point, the original pilot flying lets go of the controls while the new pilot flying assumes pilot responsibilities

- Pilot flying states, "You have the controls"

- There may be other variations of this to include shaking the stick, but the intent is there is always a pilot flying, and there can be no confusion to that fact

Conclusion

- Maneuvers are not flown for the sake of

- They are means to practice procedures applicable to common aircraft operations

- Less important than moving an aircraft to complete a maneuver, is the understanding the desired performance and outcome

- Remember: Pitch-Power-Configuration-Trim

- Flight maneuvers follow a set of procedures to demonstrate some aspect of the aircraft's performance

- Learn more about takeoff and landing performance in the aerodynamics and performance section

- Consistently sit in such a way that your sight picture remains constant, that is your view outside of the aircraft, by which you reference the aircraft to the horizon, should be consistent

- Remain mindful that performance calculations are usually more optimistic than actual performance

- Consider practicing maneuvers on a flight simulator to introduce yourself to maneuvers or knock off rust

- Still looking for something? Continue searching: