Approach & Landing

Approach and landing procedures enable an aircraft's transition from the en route to the terminal phase of flight.

Approach & Landing Introduction

- Approach and landings begin with appropriate descent planning

- More austere and even urban airport environments require unique confined area approaches and landing procedures

- Faced with unimproved surfaces, pilots may elect to perform soft-field approach and landing procedures so as to maximize aircraft performance

- No matter the landing type performance, every good landing starts with a stabilized approach

- Occasionally, to correct for atmospherics or errors in procedure, pilots can perform forward slips to landing to reestablish proper position

- Think you've got a solid understanding of approach and landing? Don't miss the approach and landing quiz below, and topic summary

Descent Planning, Briefing, and Descent Flow/Checklist

- Descent planning sets the pilot up for success and occurs long before the descent by gathering any relevant information or documents before landing

- Descent briefing enables the pilot to prepare for landing to mitigate one of the most dangerous phases of flight

- Finally, the descent flow/checklist is performed to ensure the aircraft is configured appropriately for the type of landing to be performed

-

Descent Planning:

- Perform descent planning calculations, if desired, and if not already completed before flight.

- Listen to ATIS/AWOS/ASOS to:

- Determine weather conditions at the airfield.

- Determine the active runway.

- Gather relevant documents you want ready during the approach and immediately after landing:

- Airport diagrams

-

Descent Briefing:

- Review each step to be performed, including but not limited to:

- Frequencies needed and information required for radio calls (i.e., ATIS information, requests)

- Type of landing to be performed

- Key airspeeds to hit

- Roll-out and runway exit plan

- Taxi plan/request (pending ATC instructions)

- Parking plan

- Review each step to be performed, including but not limited to:

-

Descent/Flow Checklist:

- Check that the mixture is full rich

- Turn on the fuel pump

- Put on shoulder harnesses

- This should include a quick briefing of the airport (i.e., runway vs. taxiway orientation to avoid a wrong surface landing) where an approach and landing procedure being conducted

-

Gust Factor:

- On all approaches, but especially crosswind approaches, you'll want to determine the gust factor

- Gust factors are agnostic to the wind direction

- To calculate, take your gusts and subtract them from the sustained wind

- If your wind is 10 knots and the gusts are 20, then we can subtract 20 from 10 to get 10 as our gust factor (half the gust)

- On approach, we'll want to add half of the gust factor to our approach speed to create a margin of safety within a gusty environment

Initial Contact

- Remember, when flying an instrument approach, approach control may clear you for an approach, but the tower clears you to land

- To provide controllers with the information they need to clear you to land, pilots must declare their intentions

- Intentions may be to conduct touch and go's, low approaches, or landing, and to where you will taxi to park

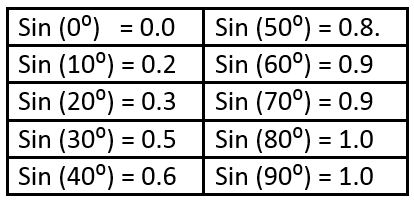

Normal Approach & Landing

- Normal approaches and landings are the building blocks from which all other landings build

- While this procedure is for normal landing, assuming the wind is blowing right down the runway, that will rarely be the case

-

Normal Approach & Landing Procedure:

- Complete the Descent Flows/Checklists

- This should include a quick briefing of the airport (i.e., runway vs. taxiway orientation to avoid a wrong surface landing) where an approach and landing procedure being conducted

- Gather any documents you may want to have ready during the approach or immediately after landing

- Talk to the tower as appropriate to the airspace you're operating within

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions]"

- Example: "Palms tower, Cessna One Seven Two Seven Victor, fives miles to the west for touch and go's"

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions], [Facility Name]"

- Example: "Palms tower, Cessna one seven two seven victor, five miles to the west for touch and goes, palms tower"

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions]"

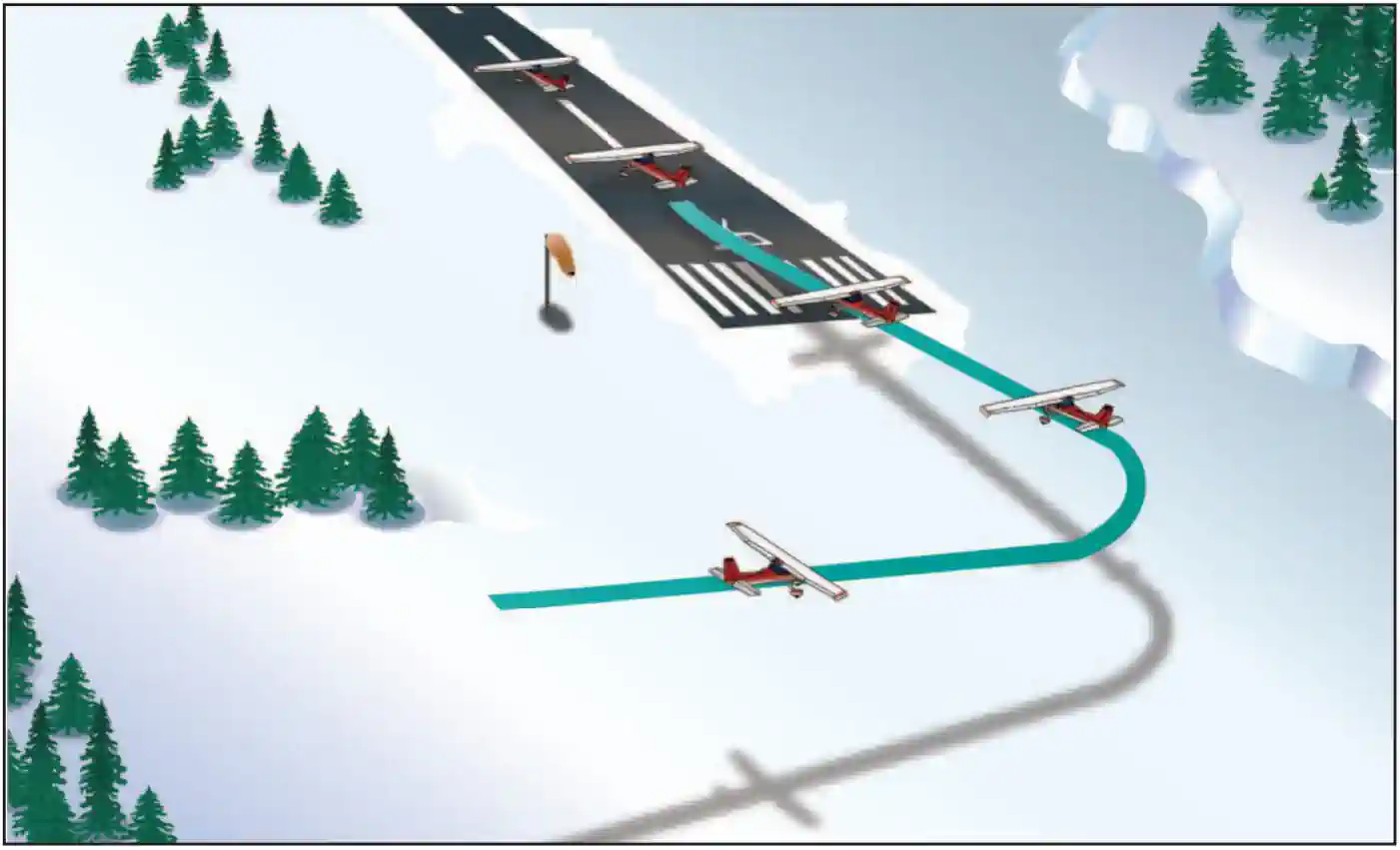

- Abide by the tower's instructions and plan to enter the traffic pattern at Traffic Pattern Altitude (TPA) on a 45° entry to the downwind, maintaining a one-half mile distance from the runway on the downwind leg

- Alternatively, if approved, you may enter the pattern through the overhead approach maneuver

- Set power to establish and maintain traffic pattern speed

- Trim as necessary

- Abeam the point of intended landing, reduce power, lower the landing gear, set the flaps, and begin a gentle descent and call

- Keeping your hand on the landing gear until given the down and locked indication will prevent forgetting

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign] abeam, gear 3 down and locked, [Landing Type]"

- ATC: "[Callsign], [Winds], cleared for [Runway], [Landing Type]"

- ATC: Cessna 1727V, wind 130 at 5 knots, runway 12, cleared to land

- Uncontrolled: None

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- At the 45° point to the intended touchdown point, commence a turn to the base leg

- ICS: "Cleared left, forward, clear right, turning [Left/Right]"

- Controlled: None

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], turning base for [Runway], [Facility Name]"

- The wind is now at your side, so depending on its strength, you will need to compensate for drift with a crab angle

- Set the flaps, then establish and maintain base leg airspeed

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- Visually verify that the final approach (including the extended final and the opposite base leg) is clear, and turn final

- ICS: "Cleared left, forward, clear right, turning [Left/Right]"

- Controlled: None

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], turning base for [Runway], [Facility Name]"

- Check your heading indicator against the runway heading to ensure you're lined up with the correct runway

- Avoid bank angles in excess of 15°

- Be mindful of wake turbulence considerations

- That is look for larger, slower, heavier aircraft and offset your flight path higher & upwind)

- ATC will generally include "caution wake turbulence" before giving winds when clearing an aircraft to land

- If landing to an airport with pilot-controlled lighting, refresh the light timer

- Remember pitch for airspeed, power for altitude.

- When landing is assured, set the flaps for landing and establish approach speed

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- Shift your scan to the glideslope indicators, if available, runway alignment, airspeed, and VSI

- By 300' above landing, complete a GUMP check

- GUMP Check:

- Gas: Fuel Selector and Pumps - SET

- Undercarriage: Gear - DOWN AND LOCKED (if applicable)

- Mixture: Mixture - FULL FORWARD

- Prop: Prop - FULL FORWARD (if applicable)

- If the approach is stabilized, call out, "300 feet, stabilized, continuing"

- If the approach is not stabilized, callout (over the ICS), "300 feet, not stabilized, going around," and execute a go-around

- When descending beneath area obstructions like buildings, trees, or otherwise, be prepared for wind shifts

- GUMP Check:

- Approaching the runway threshold, verify the runway number (heading) matches your clearance

- You are checking to verify you are landing on the correct runway as this is your last opportunity to wave off

- As you cross the threshold, begin reducing power as necessary to "roundout" and transitioning to the flare, holding the airplane 1-2 feet off the surface in ground effect, now at idle, as long as possible (to gradually dissipate forward speed)

- When within 10-20 feet, about the height of a hangar, begin the roundout

- Don't focus on the runway, but instead look long (at least a few hundred feet) to flare

- You will see the horizon flatten as if you're sitting on the ground

- Avoid closing the throttle so rapidly that an immediate increase in the rate of descent leads to a hard landing

- Touch down at minimum controllable airspeed with a power-off stall pitch attitude on the main wheels first (minimum float) and with the throttle at the idle (closed) position

- Hold the nose wheel off with back pressure throughout the roll-out; allowing settling gently

- Increase aileron deflection into the wind if present or has shifted from expected

- Maintain directional control throughout the roll-out with the rudder, slowing sufficiently before turning on a taxiway

- Exit the runway without delay at the first available taxiway or on a taxiway as instructed by ATC

- An aircraft is considered clear of the runway when all parts of the aircraft are past the runway edge and there are no restrictions to its continued movement beyond the runway holding position markings

- Proceed with taxi procedures

- Complete the Descent Flows/Checklists

-

Normal Approach and Landing Common Errors:

- Inadequate wind drift correction on the base leg

- Overshooting or undershooting the turn onto the final approach, resulting in too steep or too shallow a turn onto the final approach

- Flat or skidding turns from base leg to final approach as a result of overshooting/inadequate wind drift correction

- Poor coordination during the turn from base to final approach

- Failure to complete the landing checklist in a timely manner

- Un-stabilized approach

- Failure to adequately compensate for flap extension

- Poor trim technique on the final approach

- Attempting to maintain altitude or reach the runway using the elevator alone

- Focusing too close to the airplane, resulting in too high a round-out

- Focusing too far from the airplane, resulting in too low a round-out

- Touching down before attaining a proper landing attitude

- Failure to hold sufficient back-elevator pressure after touchdown

- Excessive braking after touchdown

-

Private Pilot (Airplane) Normal Takeoff and Climb Airman Certification Standards:

.- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with normal approach and landing with emphasis on proper use and coordination of flight controls

- Note: If a crosswind condition does not exist, the applicant’s knowledge of crosswind elements must be evaluated through oral testing

- References: AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8083-23 (Seaplane, Skiplane, and Float/Ski Equipped Helicopter Operations Handbook), FAA-H-8083-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge); POH/AFM

- Private Pilot (Airplane) Normal Approach and Landing Lesson Plan.

Normal Approach and Landing Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

PA.IV.B.K1:

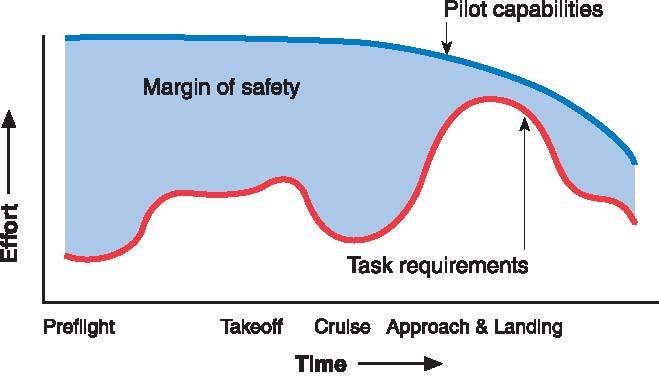

A stabilized approach, including energy management concepts. -

PA.IV.B.K2:

Effects of atmospheric conditions, including wind, on approach and landing performance. -

PA.IV.B.K3:

Wind correction techniques on approach and landing.

Normal Approach and Landing Risk Management:

The applicant is able to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with:-

PA.IV.B.R1:

Selection of runway/landing surface, approach path, and touchdown area based on pilot capability, aircraft performance and limitations, available distance, and wind. -

PA.IV.B.R2:

Effects of:-

PA.IV.B.R2a:

Crosswind. -

PA.IV.B.R2b:

Windshear. -

PA.IV.B.R2c:

Tailwind. -

PA.IV.B.R2d:

Wake turbulence. -

PA.IV.B.R2e:

Runway surface/condition.

-

-

PA.IV.B.R3:

Planning for:-

PA.IV.B.R3a:

Rejected landing and go-around. -

PA.IV.B.R3b:

Land and hold short operations (LAHSO).

-

-

PA.IV.B.R4:

Collision hazards. -

PA.IV.B.R5:

Low altitude maneuvering, including stall, spin, or controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). -

PA.IV.B.R6:

Distractions, task prioritization, loss of situational awareness, or disorientation.

Normal Approach and Landing Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

PA.IV.B.S1:

Complete the appropriate checklist(s). -

PA.IV.B.S2:

Make radio calls as appropriate. -

PA.IV.B.S3:

Ensure the airplane is aligned with the correct/assigned runway or landing surface. -

PA.IV.B.S4:

Scan the runway or landing surface and adjoining area for traffic and obstructions. -

PA.IV.B.S5:

Select and aim for a suitable touchdown point considering the wind, landing surface, and obstructions. -

PA.IV.B.S6:

Establish the recommended approach and landing configuration, airspeed, and trim, and adjust pitch attitude and power as required to maintain a stabilized approach. -

PA.IV.B.S7:

Maintain manufacturer’s published approach airspeed or in its absence not more than 1.3 times the stalling speed or the minimum steady flight speed in the landing configuration (VSO), +10/-5 knots with gust factor applied. -

PA.IV.B.S8:

Maintain directional control and appropriate crosswind correction throughout the approach and landing. -

PA.IV.B.S9:

Make smooth, timely, and correct control application during round out and touchdown. -

PA.IV.B.S10:

Touch down at a proper pitch attitude, within 400 feet beyond or on the specified point, with no side drift, and with the airplane’s longitudinal axis aligned with and over the runway center/landing path. -

PA.IV.B.S11:

Execute a timely go-around if the approach cannot be made within the tolerances specified above or for any other condition that may result in an unsafe approach or landing. -

PA.IV.B.S12:

Utilize runway incursion avoidance procedures.

-

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Normal Approach and Landing Airman Certification Standards:

.- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with normal approach and landing with emphasis on proper use and coordination of flight controls

- Note: If a crosswind condition does not exist, the applicant’s knowledge of crosswind elements must be evaluated through oral testing

- References: AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8083-23 (Seaplane, Skiplane, and Float/Ski Equipped Helicopter Operations Handbook), FAA-H-8083-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge); POH/AFM

- Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Normal Approach and Landing Lesson Plan

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Normal Approach and Landing Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

CA.IV.B.K1:

A stabilized approach, including energy management concepts. -

CA.IV.B.K2:

Effects of atmospheric conditions, including wind, on approach and landing performance. -

CA.IV.B.K3:

Wind correction techniques on approach and landing.

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Normal Approach and Landing Risk Management:

The applicant is able to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with:-

CA.IV.B.R1:

Selection of runway/landing surface, approach path, and touchdown area based on pilot capability, aircraft performance and limitations, available distance, and wind. -

CA.IV.B.R2:

Effects of:-

CA.IV.B.R2a:

Crosswind. -

CA.IV.B.R2b:

Windshear. -

CA.IV.B.R2c:

Tailwind. -

CA.IV.B.R2d:

Wake turbulence. -

CA.IV.B.R2e:

Runway surface/condition.

-

-

CA.IV.B.R3:

Planning for:-

CA.IV.B.R3a:

Rejected landing and go-around. -

CA.IV.B.R3b:

Land and hold short operations (LAHSO).

-

-

CA.IV.B.R4:

Collision hazards. -

CA.IV.B.R5:

Low altitude maneuvering, including stall, spin, or controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). -

CA.IV.B.R6:

Distractions, task prioritization, loss of situational awareness, or disorientation.

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Normal Approach and Landing Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

CA.IV.B.S1:

Complete the appropriate checklist(s). -

CA.IV.B.S2:

Make radio calls as appropriate. -

CA.IV.B.S3:

Ensure the airplane is aligned with the correct/assigned runway or landing surface. -

CA.IV.B.S4:

Scan the runway or landing surface and adjoining area for traffic and obstructions. -

CA.IV.B.S5:

Select and aim for a suitable touchdown point considering the wind, landing surface, and obstructions. -

CA.IV.B.S6:

Establish the recommended approach and landing configuration, airspeed, and trim, and adjust pitch attitude and power as required to maintain a stabilized approach. -

CA.IV.B.S7:

Maintain manufacturer’s published approach airspeed or in its absence not more than 1.3 times the stalling speed or the minimum steady flight speed in the landing configuration (VSO), ±5 knots with gust factor applied. -

CA.IV.B.S8:

Maintain directional control and appropriate crosswind correction throughout the approach and landing. -

CA.IV.B.S9:

Make smooth, timely, and correct control application during round out and touchdown. -

CA.IV.B.S10:

Touch down at a proper pitch attitude, within 200 feet beyond or on the specified point, with no side drift, and with the airplane’s longitudinal axis aligned with and over the runway center/landing path. -

CA.IV.B.S11:

Execute a timely go-around if the approach cannot be made within the tolerances specified above or for any other condition that may result in an unsafe approach or landing. -

CA.IV.B.S12:

Utilize runway incursion avoidance procedures.

Crosswind Approach & Landing

- The goal of a crosswind landing is to safely and accurately establish and maintain a stabilized approach to landing, correcting for a crosswind during the approach, touchdown, and roll-out

-

Determining Crosswind Component:

- Pilots calculate crosswinds through many methods that each serve a purpose, depending on the flight phase.

- When calculating the crosswind, always use the full gust component, meaning calculate crosswind as a "worst case" scenario

- Consider your source for winds (true vs. magnetic) and remember if it's written, it's true; if it's spoken, it's magnetic:

- ATC reports, a windsock, or ATIS are magnetic

- METARs provide winds in true, but pilots can convert to magnetic.

- Remember, winds are variable, too, so only bother converting if operating at significant deviations.

- When calculating the crosswind, always use the full gust component, meaning calculate crosswind as a "worst-case" scenario.

-

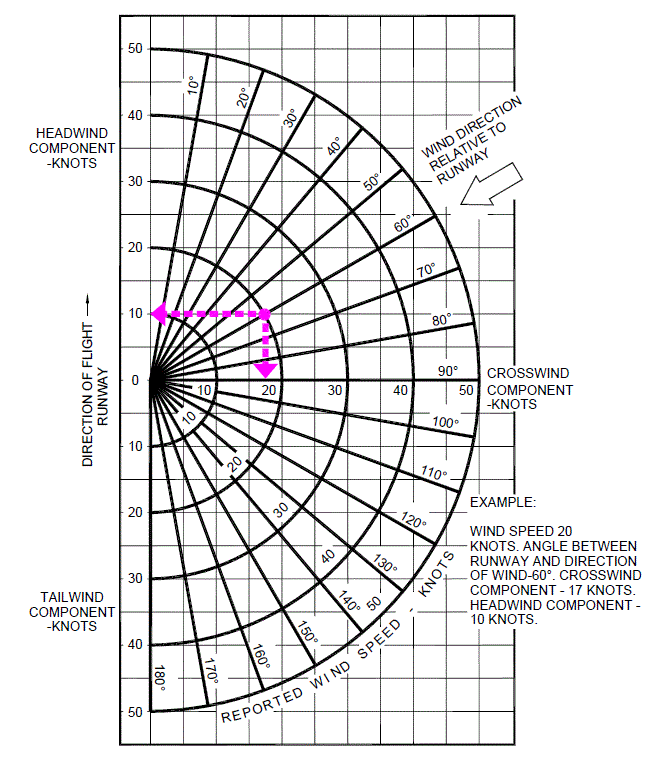

Chart Method:

- Crosswind charts are in nearly every POH/PIM, but are not aircraft-specific, so any will do.

- Using the example provided in [Figure 3], plot your point using the number of degrees off the runway heading, with the full gust component as strength.

- Let's say we're going to land at runway 360, and the wind is coming from 020 at 20 knots.

- We'll plot the wind strength at the 20° radial line (representing 20° off the runway) on the 20° point (representing the wind strength).

- From the plotted point, we move straight left for the headwind component: roughly 19 knots.

- We can also move straight down for the crosswind component: approximately 6 knots.

-

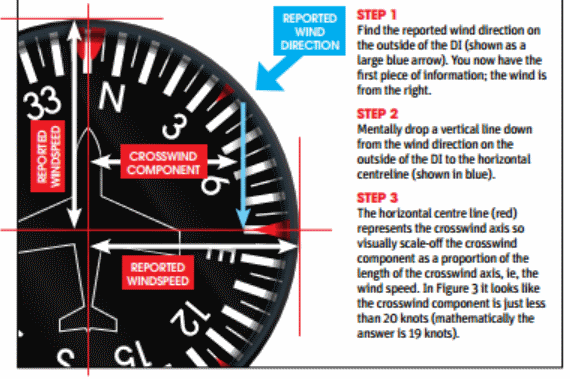

Heading Indicator Rule of Thumb:

- Find the reported wind direction on the outside of the DI (shown as a large blue arrow). You now have the first piece of information: the wind is from the right. [Figure 4]

- Mentally drop a vertical line down from the wind direction on the outside of the DI to the horizontal centerline (shown in blue).

- The horizontal center line (red) represents the crosswind axis, so visually scale off the crosswind component as a proportion of the length of the crosswind axis, i.e., the wind speed.

- Using our example, this means our crosswind component is just less than 20 knots (mathematically, the answer is 19 knots).

-

Sixths Rule of Thumb:

- If the angle is 10°, then the crosswind component equals 1/6 of the wind strength.

- If the angle is 20°, then the crosswind component equals 2/6 (1/3) of the wind strength.

- If the angle is 30°, then the crosswind component equals 3/6 (1/2) of the wind strength.

- If the angle is 40°, then the crosswind component equals 4/6 (2/3) of the wind strength.

- If the angle is 50°, then the crosswind component equals 5/6 of the wind strength.

- If the angle is 60° or greater, then the crosswind component equals the wind strength.

-

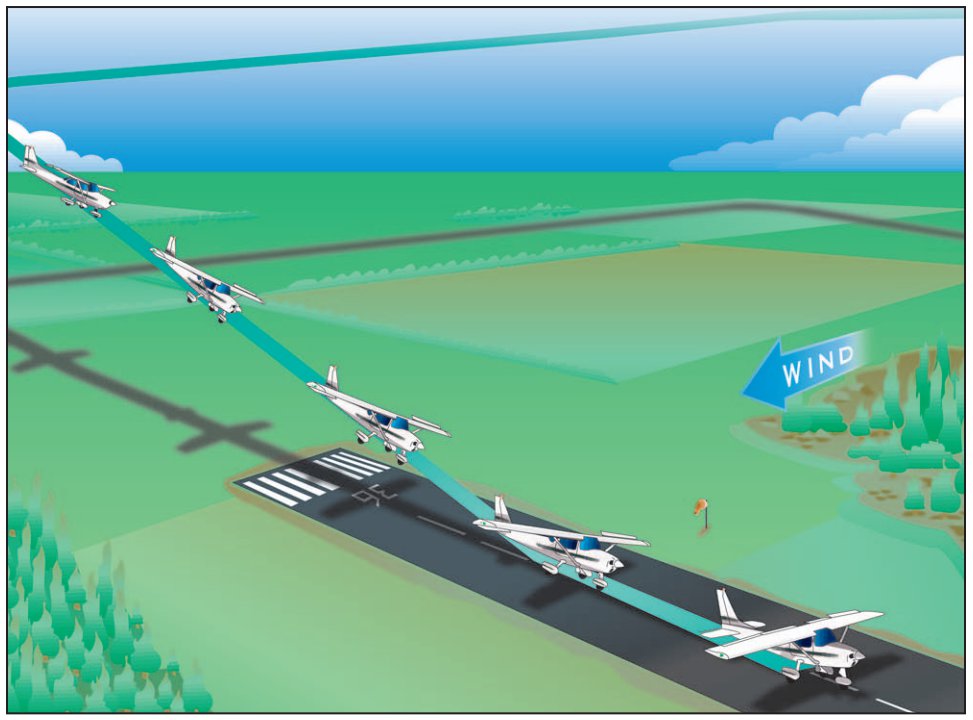

Mathematical Formula:

- The formula for crosswind component = Wind Speed x Sin (Wind Angle). [Figure 5]

- Example: If the wind is 310° at 17 knots and you line up to 330°, you can see you have a wind angle of 20°.

- Refer to the chart to find that the sine of 20° is 0.3. Then, multiply this value by the wind component of 17 knots to obtain a crosswind component of 5 knots.

-

Crosswind Compensation Techniques:

-

Slip:

- A slip is a cross-control procedure where you are using "wing-low, top-rudder" to track the aircraft straight for the purposes of altitude loss (forward-slip) or crosswind compensation (side-slip)

- In doing this, you will need to lower the nose as the increase in drag without an increase in thrust will cause a rapid loss of airspeed, risking a stall

- Simply stated, the higher the angle of bank, the lower the nose must be

- A forward-slip allows pilots to increase the aircraft's rate of descent without increasing airspeed in the process

- A side-slip, however, allows pilots to compensate for a crosswind on final approach

-

Side-slip:

- A side-slip is used to compensate for a crosswind on final approach

- First, you apply the aileron into the wind to compensate for the crosswind blowing you off centerline

- Next, you use the rudder to maintain alignment with the runway centerline

- Think: "Point your nose with your toes"

- The horizontal component of lift forces the airplane to move sideways toward the low-wing

- The aircraft's rudder is used to align to the center while the wings are dripped (toward the wind) to maintain track (drift)

- Held all the way to touchdown, this will result in the low side wheel touching down first, followed by the high wheel, and lastly, the nose/tail wheel

- Note that when performing a slip, the Pilot Operating Handbook may impose certain restrictions such as:

- Avoiding slips with full flaps

- Avoiding slips for prolonged periods, which may result in fuel ports becoming uncovered

- Airspeed indications may vary due to static ports receiving direct wind

- If your static port is located on the left side of the fuselage, a slip using the right rudder will cause the perceived static pressure to be higher than actual as ram air is forced into the static port, resulting in your indicated airspeed being less than actual. Therefore, it would normally be advisable to maintain an airspeed comfortably within the middle range of the white arc (flap operating range) to avoid being either too close to a cross-control stall or a flap over-speed condition

- Ensure to check POH for side-slip limitations, as some aircraft do not allow them with full flaps

- A slip is a cross-control procedure where you are using "wing-low, top-rudder" to track the aircraft straight for the purposes of altitude loss (forward-slip) or crosswind compensation (side-slip)

-

Crab:

- Coordinated flight whereby you are pointing the nose of the aircraft upwind enough to keep the airplane's ground track straight

- The angle by which the aircraft is flying relative to the runway is considered the crosswind correction

- It is most preferable, in general aviation, to fly a crab and transition to a slip for landing to avoid side-loading the landing gear

- At some point during the final approach, a transition from crab to side-slip for the landing flare and touchdown should be made

-

-

Crosswind Control Mechanics:

- Crab on a final and slip to the landing

- The aircraft will want to weathervane, pointing into the wind

- The rudder is necessary to maintain directional control

- As speed decreases, the control surfaces become less effective as you transition from flying to a taxi, thereby requiring more input to achieve the same effect, leading to increasing control inputs as you decelerate

- The crosswind effect will never completely disappear, meaning that some input will remain

- If, when taking out your inputs, the upwind wing is allowed to rise, it will expose more surface to the crosswind, and a side-skipping action may result

- This side-skipping imposes severe side stresses on the landing gear and could result in structural failure

- As both main wheels contact the runway, ground friction resists drifting

-

Crosswind Approach & Landing Procedure:

- Complete the Descent Flows/Checklists

- This should include a quick briefing of the airport (i.e., runway vs. taxiway orientation to avoid a wrong surface landing) where an approach and landing procedure being conducted

- Gather any documents you may want to have ready during the approach or immediately after landing

- Talk to the tower as appropriate to the airspace you're operating within

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions]"

- Example: "Palms tower, Cessna One Seven Two Seven Victor, fives miles to the west for touch and go's"

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions], [Facility Name]"

- Example: "Palms tower, Cessna one seven two seven victor, five miles to the west for touch and goes, palms tower"

- Abide by the tower's instructions and plan to enter the traffic pattern at Traffic Pattern Altitude (TPA) on a 45° entry to the downwind, maintaining a one-half mile distance from the runway on the downwind leg

- Alternatively, if approved, you may enter the pattern through the overhead approach maneuver

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions]"

- Set power to establish and maintain traffic pattern speed

- Trim as necessary

- Abeam the point of intended landing, reduce power, set the flaps, lower the landing gear, and begin a gentle descent and call

- Keeping your hand on the landing gear until given the down and locked indication will prevent forgetting

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign] abeam, gear 3 down and locked, [Landing Type]"

- ATC: "[Callsign], [Winds], cleared for [Runway], [Landing Type]"

- Uncontrolled: None

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- At the 45° point to the intended touchdown point (or as appropriate for wind conditions), commence a turn to the base leg

- ICS: "Cleared left, forward, clear right, turning [Left/Right]"

- Controlled: None

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], turning base for [Runway], [Facility Name]"

- The wind is now at your side, so depending on its strength, you will need to compensate for drift with a crab angle

- Set the flaps, then establish and maintain base leg airspeed

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- Visually verify that the final approach (including the extended final and the opposite base leg) is clear, and turn final

- ICS: "Cleared left, forward, clear right, turning [Left/Right]"

- Controlled: None

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], turning base for [Runway], [Facility Name]"

- Check your heading indicator against the runway heading to ensure you're lined up with the correct runway

- Avoid bank angles in excess of 15°

- Be mindful of wake turbulence considerations

- That is look for larger, slower, heavier aircraft and offset your flight path higher & upwind)

- If landing to an airport with pilot-controlled lighting, refresh the timer

- Remember pitch for airspeed, power for altitude.

- When landing is assured, set the flaps for landing and establish approach speed (+1/2 gust factor, if applicable)

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- Transition from a crab to a slip

- Shift your scan to the glideslope indicators, if available, runway alignment, airspeed, and VSI

- By 300' above landing, complete a GUMP check

- GUMP Check:

- Gas: Fuel Selector and Pumps - SET

- Undercarriage: Gear - DOWN AND LOCKED (if applicable)

- Mixture: Mixture - FULL FORWARD

- Prop: Prop - FULL FORWARD (if applicable)

- If the approach is stabilized, call out, "300 feet, stabilized, continuing"

- If the approach is not stabilized, callout (over the ICS), "300 feet, not stabilized, going around," and execute a go-around

- When descending beneath area obstructions like buildings, trees, or otherwise, be prepared for wind shifts

- GUMP Check:

- Approaching the runway threshold, verify the runway number (heading) matches your clearance

- You are checking to verify you are landing on the correct runway, as this is your last opportunity to go-around

- As you cross the threshold, begin reducing power as necessary to "roundout" and transitioning to the flare, holding the airplane 1-2 feet off the surface in ground effect, now at idle, as long as possible (to gradually dissipate forward speed)

- When within 10-20 feet, about the height of a hangar, begin the roundout

- Don't focus on the runway, but instead look long (at least a few hundred feet) to flare

- You will see the horizon flatten as if you're sitting on the ground

- Avoid closing the throttle so rapidly that an immediate increase in the rate of descent leads to a hard landing

- Touch down at minimum controllable airspeed with a power-off stall pitch attitude on the main wheels first (minimum float) and with the throttle at the idle (closed) position

- Hold the nose wheel off with back pressure throughout the roll-out; allowing settling gently

- Once the aircraft touches down, it will tend to find the centerline on its own; you need to be judicious with your inputs to avoid any induced oscillations

- Subsequent runway centerline tracking requires only small rudder inputs to initiate directional corrections

- Increase aileron deflection into the wind as you decelerate due to less airflow, decreasing aileron effectiveness

- Maintain directional control throughout the roll-out with the rudder, slowing sufficiently before turning on a taxiway

- Remember to maintain taxi control inputs for winds

- Exit the runway without delay at the first available taxiway or on a taxiway as instructed by ATC

- An aircraft is considered clear of the runway when all parts of the aircraft are past the runway edge, and there are no restrictions to its continued movement beyond the runway holding position markings

- Proceed with taxi procedures

- Complete the Descent Flows/Checklists

-

Crosswind Approach and Landing Common Errors:

- Attempting to land in crosswinds that exceed the airplane's maximum demonstrated crosswind component.

- Inadequate compensation for wind drift on the turn from base leg to final approach, resulting in under or shooting.

- Flat or skidding turns from base leg to final approach as a result of overshooting/inadequate wind drift correction.

- Poor coordination during the turn from base to final approach.

- Failure to complete the landing checklist in a timely manner.

- Un-stabilized approach.

- Inadequate compensation for wind drift on the final approach (allowing upwind wing to rise).

- Maintaining too much speed on the final approach to compensate for winds.

- Failure to adequately compensate for flap extension.

- Poor trim technique on the final approach.

- Failure to compensate for increased drag during side-slip, resulting in excessive sink rate and/or too low an airspeed.

- Attempting to maintain altitude or reach the runway using the elevator alone.

- Focusing too close to the airplane, resulting in too high a round out.

- Focusing too far from the airplane, resulting in too low a round out.

- Touching down before attaining a proper landing attitude.

- Failure to apply appropriate flight control inputs during roll-out, causing the aircraft to drift, weathervane, or lean (allowing upwind wing to rise).

- Failure to maintain directional control on roll-out.

- Touchdown while drifting (side-loading).

- Excessive airspeed on touchdown, resulting in a late touchdown.

- Excessive braking after touchdown.

- Slip:

- Failure to reduce power to idle.

- Failure to add or increase flaps when available.

- Failure to apply and maintain full rudder deflection.

- Failure to use appropriate rudder/aileron combination during a crosswind situation.

- Failure to reduce pitch to maintain proper safe gliding airspeed.

Short-Field Approach & Landing

- The goal of the short-field approach and landing is to maximize aircraft performance to safely and accurately land when runway distance is limited

- The approach is made with minimum engine power commensurate with flying towards the aiming point on the runway

- This will result in a steeper approach than otherwise flown with other landing procedures

- The speed must be reduced progressively as the aircraft's height reduces, and after reaching the airspeed for the final approach, it must be maintained accurately

- After touchdown, the pilot applies maximum wheel braking and maximum up-elevator to minimize distance traveled

- Wing-flaps are sometimes retracted to allow better braking performance

- Tips:

- Touchdown as close to the approach end as safely possible

- Utilize maximum braking available

- Keep tires on the ground to keep friction

- Land into a headwind

- Land as the lowest weight possible

-

Short-Field Approach & Landing Procedure:

- Complete the Descent Flows/Checklists

- This should include a quick briefing of the airport (i.e., runway vs. taxiway orientation to avoid a wrong surface landing) where, and approach and landing procedure being conducted

- Gather any documents you may want to have ready during the approach or immediately after landing

- Talk to the tower as appropriate to the airspace you're operating within

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions]"

- Example: "Palms tower, Cessna one seven two seven victor, fives miles to the west for touch and go's"

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions], [Facility Name]"

- Example: "Palms tower, Cessna One Seven Two Seven Victor, five miles to the west for touch and goes, palms tower"

- Abide by the tower's instructions and plan to enter the traffic pattern at Traffic Pattern Altitude (TPA) on a 45° entry to the downwind, maintaining a one-half mile distance from the runway on the downwind leg

- Alternatively, if approved, you may enter the pattern through the overhead approach maneuver

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions]"

- Set power to establish and maintain traffic pattern speed

- Trim as necessary

- Abeam the point of intended landing, reduce power, lower the landing gear, set the flaps, begin a gentle descent, and call

- Keeping your hand on the landing gear until given the down and locked indication will prevent forgetting

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign] abeam, gear 3 down and locked, [Landing Type]"

- ATC: "[Callsign], [Winds], cleared for [Runway], [Landing Type]"

- Uncontrolled: None

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- At the 45° point to the intended touchdown point (or as appropriate for wind conditions), commence a turn to the base leg

- ICS: "Cleared left, forward, clear right, turning [Left/Right]"

- Controlled: None

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], turning base for [Runway], [Facility Name]"

- The wind is now at your side, so depending on its strength, you will need to compensate for drift with a crab angle

- Set the flaps, then establish and maintain base leg airspeed

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- Visually verify that the final approach (including the extended final and the opposite base leg) is clear, and turn final

- ICS: "Cleared left, forward, clear right, turning [Left/Right]"

- Controlled: None

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], turning base for [Runway], [Facility Name]"

- Check your heading indicator against the runway heading to ensure you're lined up with the correct runway

- Avoid bank angles in excess of 15°

- Be mindful of wake turbulence considerations

- That is look for larger, slower, heavier aircraft and offset your flight path higher & upwind)

- If landing to an airport with pilot-controlled lighting, refresh the timer

- Remember pitch for airspeed, power for altitude.

- When landing is assured, set the flaps for landing and establish approach speed (+1/2 gust factor, if applicable)

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- Transition from a crab to a slip

- Shift your scan to the glideslope indicators, if available, runway alignment, airspeed, and VSI

- By 300' above landing, complete a GUMP check

- GUMP Check:

- Gas: Fuel Selector and Pumps - SET

- Undercarriage: Gear - DOWN AND LOCKED (if applicable)

- Mixture: Mixture - FULL FORWARD

- Prop: Prop - FULL FORWARD (if applicable)

- If the approach is stabilized, call out, "300 feet, stabilized, continuing"

- If the approach is not stabilized, callout (over the ICS), "300 feet, not stabilized, going around," and execute a go-around

- When descending beneath area obstructions like buildings, trees, or otherwise, be prepared for wind shifts

- GUMP Check:

- Approaching the runway threshold, verify the runway number (heading) matches your clearance

- You are checking to verify you are landing on the correct runway, as this is your last opportunity to go-around

- As you cross the threshold, begin reducing power as necessary to "round-out" and transitioning to the flare, holding the airplane 1-2 feet off the surface in ground effect, now at idle, as long as possible (to gradually dissipate forward speed)

- When within 10-20 feet, about the height of a hangar, begin the roundout

- Don't focus on the runway, but instead look long (at least a few hundred feet) to flare

- You will see the horizon flatten as if you're sitting on the ground

- Avoid closing the throttle so rapidly that an immediate increase in the rate of descent leads to a hard landing

- Touch down at minimum controllable airspeed with a power-off stall pitch attitude on the main wheels first (minimum float) and with the throttle at the idle (closed) position

- Hold the nose wheel off with back pressure throughout the roll-out, settling gently

- Increase aileron deflection into the wind if present or has shifted from expected

- Increase "up" elevator to increase braking effectiveness

- At nose wheel touch down:

- Callout (over the ICS), "flaps up, max braking"

- Retract the flaps to the up (0°) position (for maximum braking effectiveness)

- Hold the control wheel full back, and

- Apply braking as necessary to stop within the shortest distance possible, consistent with safety and controllability

- Maintain directional control throughout the roll-out with the rudder, slowing sufficiently before turning on a taxiway

- Reference board speeds: you should be traveling no faster than twice the distance remaining

- Example: at the 3 board, you should be traveling no more than 60 knots

- If required, raise the flaps, which decreases lift over the wings and, therefore, increase weight on the brakes

- Exit the runway without delay at the first available taxiway or on a taxiway as instructed by ATC

- An aircraft is considered clear of the runway when all parts of the aircraft are past the runway edge, and there are no restrictions to its continued movement beyond the runway holding position markings

- Proceed with taxi procedures

- Complete the Descent Flows/Checklists

-

Short-Field Approach & Landing Common Errors:

- Inadequate wind drift correction on the base leg

- Overshooting or undershooting the turn onto the final approach, resulting in too steep or too shallow a turn onto the final approach

- Flat or skidding turns from base leg to final approach as a result of overshooting/inadequate wind drift correction

- Poor coordination during the turn from base to final approach

- Failure to complete the landing checklist in a timely manner

- Un-stabilized approach

- Failure to adequately compensate for flap extension

- Poor trim technique on the final approach

- Attempting to maintain altitude or reach the runway using elevator control alone

- Focusing too close to the airplane, resulting in too high a round-out

- Focusing too far from the airplane, resulting in too low a round-out

- Touching down before attaining a proper landing attitude

- Failure to hold sufficient back-elevator pressure after touchdown

- Excessive and/or unnecessary braking after touchdown

- A final approach that necessitates an overly steep approach and high sink rate

- Undue delay in initiating glide path corrections

- Airspeed too low on final resulting in inability to flare properly and landing hard

- Too high an airspeed resulting in floating on round out

- Prematurely reducing power to idle on round out resulting in hard landing

- Touchdown with excessive airspeed

- Failure to maintain directional control

- Failure to recognize and abort a poor approach that cannot be completed safely

-

Private Pilot (Airplane) Short-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL):

.- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with short-field approach and landing with emphasis on proper use and coordination of flight controls

- References: AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8083-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge); POH/AFM

- Private Pilot (Airplane) Short-Field Approach and Landing Lesson Plan.

Short-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

PA.IV.F.K1:

A stabilized approach, including energy management concepts. -

PA.IV.F.K2:

Effects of atmospheric conditions, including wind, on approach and landing performance. -

PA.IV.F.K3:

Wind correction techniques on approach and landing.

Short-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Risk Management:

The applicant is able to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with:-

PA.IV.F.R1:

Selection of runway based on pilot capability, airplane performance and limitations, available distance, and wind. -

PA.IV.F.R2:

Effects of:-

PA.IV.F.R2a:

Crosswind. -

PA.IV.F.R2b:

Windshear. -

PA.IV.F.R2c:

Tailwind. -

PA.IV.F.R2d:

Wake turbulence. -

PA.IV.F.R2e:

Runway surface/condition.

-

-

PA.IV.F.R3:

Planning for:-

PA.IV.F.R3a:

Rejected landing and go-around. -

PA.IV.F.R3b:

Land and hold short operations (LAHSO).

-

-

PA.IV.F.R4:

Collision hazards. -

PA.IV.F.R5:

Low altitude maneuvering, including stall, spin, or controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). -

PA.IV.F.R6:

Distractions, task prioritization, loss of situational awareness, or disorientation.

Short-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

PA.IV.F.S1:

Complete the appropriate checklist(s). -

PA.IV.F.S2:

Make radio calls as appropriate. -

PA.IV.F.S3:

Ensure the airplane is aligned with the correct/assigned runway. -

PA.IV.F.S4:

Scan the landing runway and adjoining area for traffic and obstructions. -

PA.IV.F.S5:

Select and aim for a suitable touchdown point considering the wind conditions, landing surface, and obstructions. -

PA.IV.F.S6:

Establish the recommended approach and landing configuration, airspeed, and trim, and adjust pitch attitude and power as required to maintain a stabilized approach. -

PA.IV.F.S7:

Maintain manufacturer's published approach airspeed or in its absence not more than 1.3 VSO, +10/-5 knots with gust factor applied. -

PA.IV.F.S8:

Maintain directional control and appropriate crosswind correction throughout the approach and landing. -

PA.IV.F.S9:

Make smooth, timely, and correct control application before, during, and after touchdown. -

PA.IV.F.S10:

Touch down at a proper pitch attitude within 200 feet beyond or on the specified point, threshold markings, or runway numbers, with no side drift, minimum float, and with the airplane's longitudinal axis aligned with and over the runway centerline. -

PA.IV.F.S11:

Use manufacturer’s recommended procedures for airplane configuration and braking. -

PA.IV.F.S12:

Execute a timely go-around if the approach cannot be made within the tolerances specified above or for any other condition that may result in an unsafe approach or landing. -

PA.IV.F.S13:

Use runway incursion avoidance procedures, if applicable.

-

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Short-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL):

- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with short-field approach and landing with emphasis on proper use and coordination of flight controls

- References: AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8083-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge); POH/AFM

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Short-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

PA.IV.F.K1:

A stabilized approach, including energy management concepts. -

PA.IV.F.K2:

Effects of atmospheric conditions, including wind, on approach and landing performance. -

PA.IV.F.K3:

Wind correction techniques on approach and landing.

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Short-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Risk Management:

The applicant is able to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with:-

PA.IV.F.R1:

Selection of runway based on pilot capability, airplane performance and limitations, available distance, and wind. -

PA.IV.F.R2:

Effects of:-

PA.IV.F.R2a:

Crosswind. -

PA.IV.F.R2b:

Windshear. -

PA.IV.F.R2c:

Tailwind. -

PA.IV.F.R2d:

Wake turbulence. -

PA.IV.F.R2e:

Runway surface/condition.

-

-

PA.IV.F.R3:

Planning for:-

PA.IV.F.R3a:

Rejected landing and go-around. -

PA.IV.F.R3b:

Land and holding short operations (LAHSO).

-

-

PA.IV.F.R4:

Collision hazards. -

PA.IV.F.R5:

Low altitude maneuvering, including stall, spin, or controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). -

PA.IV.F.R6:

Distractions, task prioritization, loss of situational awareness, or disorientation.

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Short-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

PA.IV.F.S1:

Complete the appropriate checklist(s). -

PA.IV.F.S2:

Make radio calls as appropriate. -

PA.IV.F.S3:

Ensure the airplane is aligned with the correct/assigned runway. -

PA.IV.F.S4:

Scan the landing runway and adjoining area for traffic and obstructions. -

PA.IV.F.S5:

Select and aim for a suitable touchdown point considering the wind conditions, landing surface, and obstructions. -

PA.IV.F.S6:

Establish the recommended approach and landing configuration, airspeed, and trim, and adjust pitch attitude and power as required to maintain a stabilized approach. -

PA.IV.F.S7:

Maintain manufacturer's published approach airspeed or in its absence not more than 1.3 VSO, ±5 knots with gust factor applied. -

PA.IV.F.S8:

Maintain directional control and appropriate crosswind correction throughout the approach and landing. -

PA.IV.F.S9:

Make smooth, timely, and correct control application before, during, and after touchdown. -

PA.IV.F.S10:

Touch down at a proper pitch attitude within 100 feet beyond or on the specified point, threshold markings, or runway numbers, with no side drift, minimum float, and with the airplane's longitudinal axis aligned with and over the runway centerline. -

PA.IV.F.S11:

Use manufacturer’s recommended procedures for airplane configuration and braking. -

PA.IV.F.S12:

Execute a timely go-around if the approach cannot be made within the tolerances specified above or for any other condition that may result in an unsafe approach or landing. -

PA.IV.F.S13:

Use runway incursion avoidance procedures, if applicable.

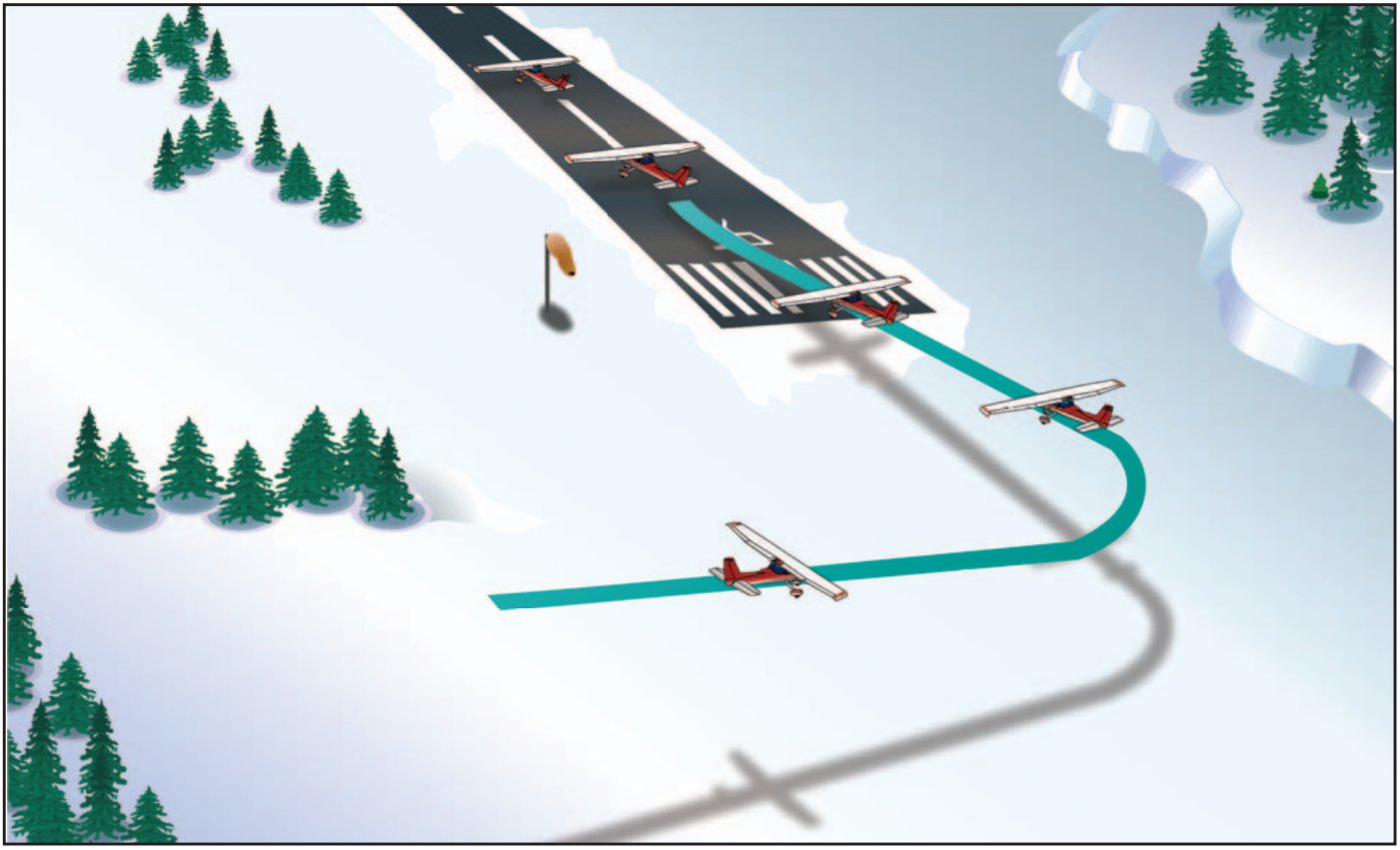

Soft/Rough-Field Approach & Landing

- The goal of the soft-field approach and landing is to maximize aircraft performance to safely and accurately land the airplane, obtaining maximum performance, by touching down at the slowest possible airspeed (energy).

- Soft/rough fields may or may not be suitable for landing based on their condition, recent weather, obstacles, etc.

- While in the pattern, pilots should pay attention to water spots, tall grass observed blowing, any markings or evidence of previous use.

- Remember any location on the map was at one point a runway, but may not be suitable now.

- Consider the risks of a low-pass in balancing the need for safety relative to careless and reckless operation (Trent Palmer Legal Case).

-

Soft/Rough-Field Approach & Landing Procedure:

- Complete the Descent Flows/Checklists

- This should include a quick briefing of the airport (i.e., runway vs. taxiway orientation to avoid a wrong surface landing) where an approach and landing procedure being conducted

- Gather any documents you may want to have ready during the approach or immediately after landing

- Talk to the tower as appropriate to the airspace you're operating within

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions]"

- Example: "Palms tower, Cessna one seven two seven victor, fives miles to the west for touch and go's"

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions], [Facility Name]"

- Example: "Palms tower, Cessna one seven two seven victor, five miles to the west for touch and goes, palms tower"

- Abide by the tower's instructions and plan to enter the traffic pattern at Traffic Pattern Altitude (TPA) on a 45° entry to the downwind, maintaining a one-half mile distance from the runway on the downwind leg

- Alternatively, if approved, you may enter the pattern through the overhead approach maneuver

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign], [Location], [Information], [Intentions]"

- Set power to establish and maintain traffic pattern speed

- Trim as necessary

- Abeam the point of intended landing, reduce power, lower the landing gear, set the flaps, and begin a gentle descent and call

- Keeping your hand on the landing gear until given the down and locked indication will prevent forgetting

- Controlled: "[Tower], [Callsign] abeam, gear 3 down and locked, [Landing Type]"

- ATC: "[Callsign], [Winds], cleared for [Runway], [Landing Type]"

- Uncontrolled: None

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- At the 45° point to the intended touchdown point (or as appropriate for wind conditions), commence a turn to the base leg

- ICS: "Cleared left, forward, clear right, turning [Left/Right]"

- Controlled: None

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], turning base for [Runway], [Facility Name]"

- The wind is now at your side, so depending on its strength, you will need to compensate for drift with a crab angle

- Set the flaps, then establish and maintain base leg airspeed

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- Visually verify that the final approach (including the extended final and the opposite base leg) is clear, and turn final

- ICS: "Cleared left, forward, clear right, turning [Left/Right]"

- Controlled: None

- Uncontrolled: "[Facility Name], [Callsign], turning base for [Runway], [Facility Name]"

- Check your heading indicator against the runway heading to ensure you're lined up with the correct runway

- Avoid bank angles in excess of 15°

- Be mindful of wake turbulence considerations

- That is, look for larger, slower, heavier aircraft and offset your flight path higher & upwind)

- If landing to an airport with pilot-controlled lighting, refresh the timer

- Remember pitch for airspeed, power for altitude.

- Maintain directional control and appropriate crosswind correction throughout the approach and landing.

- When landing is assured, set the flaps for landing and establish approach speed (+1/2 gust factor, if applicable)

- Anticipate the balloon effect when lowering the flaps

- Trim as necessary

- Transition from a crab to a slip

- Shift your scan to the glideslope indicators, if available, runway alignment, airspeed, and VSI

- By 300' above landing, complete a GUMP check

- GUMP Check:

- Gas: Fuel Selector and Pumps - SET

- Undercarriage: Gear - DOWN AND LOCKED (if applicable)

- Mixture: Mixture - FULL FORWARD

- Prop: Prop - FULL FORWARD (if applicable)

- If the approach is stabilized, callout (over the ICS), "300 feet, stabilized, continuing"

- If the approach is not stabilized, callout, "300 feet, not stabilized, going around," and execute a go-around

- When descending beneath area obstructions like buildings, trees, or otherwise, be prepared for wind shifts

- GUMP Check:

- Approaching the runway threshold, verify the runway number (heading) matches your clearance

- You are checking to verify you are landing on the correct runway, as this is your last opportunity to go-around

- As you cross the threshold, begin reducing power as necessary to "roundout" and transitioning to the flare, holding the airplane 1-2 feet off the surface in ground effect, now at idle, as long as possible (to gradually dissipate forward speed)

- Use power throughout the level-off and touchdown to ensure touching down at the slowest possible speed

- When within 10-20 feet, about the height of a hangar, begin the roundout

- Don't focus on the runway, but instead look long (at least a few hundred feet) to flare

- You will see the horizon flatten as if you're sitting on the ground

- Avoid closing the throttle so rapidly that an immediate increase in the rate of descent leads to a hard landing

- Touch down at minimum controllable airspeed with a power-off stall pitch attitude on the main wheels first (minimum float) and with the throttle at the idle (closed) position

- Hold the nose wheel off with back pressure throughout the roll-out, settling gently

- Touch down on the main wheels first, holding the nose wheel off with back pressure throughout the roll-out; allow settling gently

- Use power and control wheel back pressure (elevator deflection) to control the rate at which the airplane's weight is transferred to the main wheels

- Maintain directional control throughout the roll-out, slowing sufficiently before turning onto a taxiway

- Conduct all taxi operations with the control wheel fully aft

- On softer surfaces, additional power may be needed to maintain taxi speed and avoid becoming stuck

- Avoid the use of breaks to prevent imposing a heavy load on the nose gear, causing the nose gear to "dig" into the soft surface

- Complete the Descent Flows/Checklists

-

Soft/Rough-Field Approach & Landing Common Errors:

- Failure to review AFM/POH and performance charts before takeoff

- Failure to adequately clear the area

- Insufficient back-elevator pressure during initial takeoff roll resulting in inadequate AOA

- Failure to cross-check engine instruments for indications of proper operation after applying power

- Poor directional control

- Climbing too high after lift-off and not leveling off low enough to maintain ground effect attitude

- Abrupt and/or excessive elevator control while attempting to level off and accelerate after liftoff

- Allowing the airplane to "mush" or settle, resulting in an inadvertent touchdown after lift-off

- Attempting to climb out of ground effect area before attaining sufficient climb speed

- Failure to anticipate an increase in pitch attitude as the airplane climbs out of ground effect

-

Soft/Rough-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Airman Certification Standards:

.- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with soft-field approach and landing with emphasis on proper use and coordination of flight controls

- References: AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8083-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge); POH/AFM

- Soft/Rough-Field Approach and Landing Lesson Plan

Soft/Rough-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

PA.IV.D.K1:

A stabilized approach, to include energy management concepts. -

PA.IV.D.K2:

Effects of atmospheric conditions, including wind, on approach and landing performance. -

PA.IV.D.K3:

Wind correction techniques on approach and landing.

Soft/Rough-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Risk Management:

The applicant is able to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with:-

PA.IV.D.R1:

Selection of runway based on pilot capability, airplane performance and limitations, available distance, and wind. -

PA.IV.D.R2:

Effects of:-

PA.IV.D.R2a:

Crosswind. -

PA.IV.D.R2b:

Windshear. -

PA.IV.D.R2c:

Tailwind. -

PA.IV.D.R2d:

Wake turbulence. -

PA.IV.D.R2e:

Landing surface/condition.

-

-

PA.IV.D.R3:

Planning for:-

PA.IV.D.R3a:

Rejected landing and go-around. -

PA.IV.D.R3b:

Land and hold short operations (LAHSO).

-

-

PA.IV.D.R4:

Collision hazards. -

PA.IV.D.R5:

Low altitude maneuvering, including stall, spin, or controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). -

PA.IV.D.R6:

Distractions, task prioritization, loss of situational awareness, or disorientation.

Soft/Rough-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL) Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

PA.IV.D.S1:

Complete the appropriate checklist(s). -

PA.IV.D.S2:

Make radio calls as appropriate. -

PA.IV.D.S3:

Ensure the airplane is aligned with the correct/assigned runway. -

PA.IV.D.S4:

Scan the landing runway and adjoining area for traffic and obstructions. -

PA.IV.D.S5:

Select and aim for a suitable touchdown point considering the wind, landing surface, and obstructions. -

PA.IV.D.S6:

Establish the recommended approach and landing configuration, airspeed, and trim, and adjust pitch attitude and power as required to maintain a stabilized approach. -

PA.IV.D.S7:

Maintain manufacturer's published approach airspeed or in its absence not more than 1.3 VSO, +10/-5 knots with gust factor applied. -

PA.IV.D.S8:

Maintain directional control and appropriate crosswind correction throughout the approach and landing. -

PA.IV.D.S9:

Make smooth, timely, and correct control inputs during the round out and touchdown, and, for tricycle gear airplanes, keep the nose wheel off the surface until loss of elevator effectiveness. -

PA.IV.D.S10:

Touch down at a proper pitch attitude with minimum sink rate, no side drift, and with the airplane's longitudinal axis aligned with the center of the runway. -

PA.IV.D.S11:

Maintain elevator as recommended by manufacturer during rollout and exit the "soft" area at a speed that would preclude sinking into the surface. -

PA.IV.D.S12:

Execute a timely go-around if the approach cannot be made within the tolerances specified above or for any other condition that may result in an unsafe approach or landing. -

PA.IV.D.S13:

Maintain proper position of the flight controls and sufficient speed to taxi while on the soft surface.

Confined Area Approach and Landing (ASES, AMES) Airman Certification Standards

- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with confined area approach and landing

- References: AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8083-23 (Seaplane, Skiplane, and Float/Ski Equipped Helicopter Operations Handbook), FAA-H-8083-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge); POH/AFM

- Confined area approach and landing lesson plan

Confined Area Approach and Landing (ASES, AMES) Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

PA.IV.H.K1:

A stabilized approach, including energy management concepts. -

PA.IV.H.K2:

Effects of atmospheric conditions, including wind, on approach and landing performance.- Landing performance information

-

PA.IV.H.K3:

Wind correction techniques on approach and landing.

Confined Area Approach and Landing (ASES, AMES) Risk Management:

The applicant is able to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with:-

PA.IV.H.R1:

Selection of approach path and touchdown area based on pilot capability, airplane performance and limitations, available distance, and wind. -

PA.IV.H.R2:

Effects of:-

PA.IV.H.R2a:

Crosswind. -

PA.IV.H.R2b:

Windshear. -

PA.IV.H.R2c:

Tailwind. -

PA.IV.H.R2d:

Wake turbulence. -

PA.IV.H.R2e:

Runway surface/condition.

-

-

PA.IV.H.R3:

Planning for a go-around and rejected landing. -

PA.IV.H.R4:

Collision hazards, to include aircraft, terrain, obstacles, wires, vehicles, persons, and wildlife. -

PA.IV.H.R5:

Low altitude maneuvering, including stall, spin, or controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). -

PA.IV.H.R6:

Distractions, task prioritization, loss of situational awareness, or disorientation.

Confined Area Approach and Landing (ASES, AMES) Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

PA.IV.H.S1:

Complete the appropriate checklist. -

PA.IV.H.S2:

Make radio calls as appropriate. -

PA.IV.H.S3:

Ensure the airplane is aligned for an approach to the correct/assigned landing surface. -

PA.IV.H.S4:

Scan the landing area for traffic and obstructions. -

PA.IV.H.S5:

Select and aim for a suitable touchdown point considering the wind, landing surface, and obstructions. -

PA.IV.H.S6:

Establish the recommended approach and landing configuration, airspeed, and trim, and adjust pitch attitude and power as required to maintain a stabilized approach. -

PA.IV.H.S7:

Maintain manufacturer's published approach airspeed or in its absence not more than 1.3 VSO, +10/-5 knots with gust factor applied. -

PA.IV.H.S8:

Maintain directional control and appropriate crosswind correction throughout the approach and landing. -

PA.IV.H.S9:

Make smooth, timely, and correct control application before, during, and after touchdown. -

PA.IV.H.S10:

Contact the water at the recommended airspeed with a proper pitch attitude for the surface conditions. -

PA.IV.H.S11:

Touch down at a proper pitch attitude, within 200 feet beyond or on the specified point, with no side drift, minimum float, and with the airplane's longitudinal axis aligned with the projected landing path. -

PA.IV.H.S12:

Execute a timely go-around if the approach cannot be made within the tolerances specified above or for any other condition that may result in an unsafe approach or landing. -

PA.IV.H.S13:

Apply elevator control as necessary to stop in the shortest distance consistent with safety.

Rejected Landings and Go-Arounds

- The traffic pattern provides standardized flow of aircraft transitioning between the approach and landing phases of flight

- This standard flow allows for predictability in an otherwise extremely dangerous environment

- The traffic pattern is the ultimate goal which began with the rectangular course with many hazards

- During a rejected landing/go-around, you're low, slow, and configured for landing (high drag)

-

- Remember that flaps increase lift, and raising those flaps therefore reduce it, requiring flaps be raised slowly and in accordance with POH

- Follow procedures and do not cause the aircraft to stall

- Uncomfortable pilots (new airplane, new airport, new airspace) are especially vulnerable to the spike in blood pressure or stress when unexpected go-around instructions are received

- Consider not pushing in full power immediately to reduce performance surprises yet still be able to achieve a positive rate of climb

- Always give yourself a decision point whereby a go-around shall be executed, and past which you've conceded to a botched landing

- Do not fly on hopes you have the performance, your charts know the answer ahead of time

- Consider the left turning tendencies associated with adding full power

- Fly your airspeeds, resist the urge to pull away from the earth even if that means touching the runway briefly

- Avoid abrupt bank or pitch changes

- Manage flap and gear positions, do not immediately retract either, don't forget to retract them all together

-

Deciding When to Discontinue an Approach

- Pilots must always be in a position to make a safe landing

- When that is determined to no longer be the case, a go-around should be executed

- Go-arounds are always "free" and a stabilized approach is unlikely to be corrected on short final

-

Rejected Landings and Go-Arounds Procedure:

- When the decision to go around is made, the throttles should be advanced to takeoff power and pitch adjusted (sequentially) to arrest the sink rate.

- As you add power you're going to start accelerating.

- Acceleration takes some time as you've got a lot of drag to fight with a rate of descent to arrest and then reverse.

- Often times the addition of power and subsequent airspeed increase is necessary before pulling the nose up as the aircraft may be on the backside of the power curve and performance therefore slower to respond

- Slow airspeed and high power creates the greatest amount of left-turning tendencies

- Anticipate right rudder inputs

- Additionally, as engine power increases, since the aircraft is normally trimmed for approach speed, the nose will also increase in pitch, risking stall

- Expect forward elevator to be required to avoid an elevator stall.

- Focus on staying on centerline in case you touch down

- With adequate airspeed, pitch for Vy or Vx (if obstructions are present).

- With adequate airspeed, the flaps should be retracted from full to an intermediate position (not all at once).

- With adequate airspeed and a positive rate of climb, the landing gear should be retracted.

- Flaps should be retracted before the landing gear for two reasons:

- First, on most airplanes, full flaps produce more drag than the extended landing gear.

- Secondly, the airplane tends to settle somewhat with flap retraction, and the landing gear should be down in the event of an inadvertent, momentary touchdown.

- Flaps should be retracted before the landing gear for two reasons:

- If the go-around was initiated due to conflicting traffic on the ground or aloft, the pilot should consider maneuvering to the side to keep the conflicting traffic in sight.

- Follow air traffic control instructions and review checklist items as appropriate.

- If the pilot desires to return for a landing, it is essential to re-accomplish the entire before-landing checklist.

- An interruption to a pilot’s habit patterns, such as a go-around, is a classic scenario for a subsequent gear-up landing

- When the decision to go around is made, the throttles should be advanced to takeoff power and pitch adjusted (sequentially) to arrest the sink rate.

-

Multiengine Rejected Landings and Go-Around Considerations:

- Many multiengine airplanes have a landing gear retraction speed significantly less than the extension speed.

- Care should be exercised during the go-around not to exceed the retraction speed.

- Many multiengine airplanes have a landing gear retraction speed significantly less than the extension speed.

-

Private Pilot (Airplane) Rejected Landings and Go-Arounds Airman Certification Standards

- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with go-around/rejected landing with emphasis on factors that contribute to landing conditions that may require a go-around

- References: AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8083-23 (Seaplane, Skiplane, and Float/Ski Equipped Helicopter Operations Handbook), FAA-H-8083-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge); POH/AFM

Private Pilot (Airplane) Go-Around/Rejected Landing Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

PA.IV.N.K1:

A stabilized approach, including energy management concepts. -

PA.IV.N.K2:

Effects of atmospheric conditions, including wind and density altitude, on a go-around or rejected landing. -

PA.IV.N.K3:

Wind correction techniques on takeoff/departure and approach/landing.

Private Pilot (Airplane) Go-Around/Rejected Landing Risk Management:

The applicant is able to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with:-

PA.IV.N.R1:

Delayed recognition of the need for a go-around/rejected landing. -

PA.IV.N.R2:

Delayed performance of a go-around at low altitude. -

PA.IV.N.R3:

Power application. -

PA.IV.N.R4:

Configuring the airplane. -

PA.IV.N.R5:

Collision hazards. -

PA.IV.N.R6:

Low altitude maneuvering, including stall, spin, or controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). -

PA.IV.N.R7:

Distractions, task prioritization, loss of situational awareness, or disorientation. -

PA.IV.N.R8:

Runway incursion. -

PA.IV.N.R9:

Managing a go-around/rejected landing after accepting a LAHSO clearance.

Private Pilot (Airplane) Go-Around/Rejected Landing Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

PA.IV.N.S1:

Complete the appropriate checklist(s). -

PA.IV.N.S2:

Make radio calls as appropriate. -

PA.IV.N.S3:

Make a timely decision to discontinue the approach to landing. -

PA.IV.N.S4:

Apply takeoff power immediately and transition to climb pitch attitude for Vx or Vy as appropriate +10/-5 knots. -

PA.IV.N.S5:

Configure the airplane after a positive rate of climb has been verified or in accordance with airplane manufacturer’s instructions. -

PA.IV.N.S6:

Maneuver to the side of the runway/landing area when necessary to clear and avoid conflicting traffic. -

PA.IV.N.S7:

Maintain VY +10/-5 knots to a safe maneuvering altitude. -

PA.IV.N.S8:

Maintain directional control and proper wind-drift correction throughout the climb. -

PA.IV.N.S9:

Use runway incursion avoidance procedures, if applicable.

-

Go-Arounds and Rejected Landings Case Studies

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: SEA01LA069:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot's failure to maintain aircraft control during the aborted takeoff. A factor was gusty crosswinds

- National Transporation Safety Board Identification: NYC01FA189:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot's failure to maintain aircraft control while maneuvering during a go-around

- Pilot Workshops Breakdown

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: SEA01LA069:

Stabilized Approaches

- A good landing starts with a stabilized approach

- The definition of a stabilized approach may vary by viewpoint, but it's essentially on or trending in a controlled manner to hit your numbers in the appropriate configuration on final

- In essence, a stabilized approach results from proper energy management

- If carrying too much energy into the flare, it is easy to balloon and land far

- If carrying too little, it is possible to land short or stall

- In essence, a stabilized approach results from proper energy management

- Approach speed is not a static number and must be calculated

- First, start with applicable charts in the pilot operating handbook

- In gusty wind conditions, consider adding half of the gust factor (i.e., if gusts to 20, add 10 knots)

- A commonly referenced optimum glide-path follows a 3:1 principle or descent ratio

- This means that for every 3 nautical miles (nm) flown over the ground, the aircraft should descend 1,000 feet, simulating a 3-degree glideslope

- According to the FAA Safety Team, the probability of being unstable can double as you increasingly fly above a "3:1" flight path profile

- In some instances, this will be with the aid of a visual glide slope indicator, while other times, are flown with a good sight picture from experience

- Lateral alignment, that is, how far left or right from the runway centerline, is relatively easy to judge

- Vertical placement on the approach, often called slope, can be harder to judge

- When assessed high, pilots must increase their descent by reducing power and pitching down to maintain airspeed

- Pilots may assess they're high by watching the touchdown point "fall" in the windscreen

- When approaching glide-slope, simultaneously increasing power and pitching up to maintain airspeed reestablishes a pilot on glide-slope

- When assessed low, pilots must decrease their descent by adding power and pitching up to maintain approach speed

- Pilots may assess they're low by watching the touchdown point "rise" in the windscreen

- When approaching glide-slope, simultaneously reducing power and pitching down to maintain airspeed restablishes a pilot on glide-slope

- When a pilot is steady on a glide slope, the touchdown point will remain static and not move up or down in the windscreen

- When assessed high, pilots must increase their descent by reducing power and pitching down to maintain airspeed

- In general, maneuvers on final (such as S-Turns for spacing) are not recommended when low and slow (go-arounds are free!)

- In the end, a stabilized approach is when speed is stabilized at proper approach speed, the sink rate a stabilized at less than 1000 FPM, and the final flap configuration at a set altitude (likely 500' above touchdown)

-

Energy Management Concepts:

- Realize that power and pitch changes to intercept the appropriate glide slope must be anticipated to avoid creating the opposite situation (low to high, high to low)

- The closer to the runway, the more sensitive these corrections will be

- As such, it is best to make large corrections early so only small corrections are necessary approaching the runway

- If climbing above glideslope, the aircraft has too much energy

- A power reduction or increase in drag is required

- If descending below glideslope, the aircraft has too little energy

- A power addition or reduction in drag is required

- If low and fast, increasing the pitch may be sufficient to climb back onto glide-slope and slow to approach speed

- The reverse is true if high and fast

- Realize that power and pitch changes to intercept the appropriate glide slope must be anticipated to avoid creating the opposite situation (low to high, high to low)

-