Fitness for Flight

Judging fitness for flight is a vital self-evaluation that every pilot (and their passengers) must conduct before any flight operation.

Introduction to Fitness for Flight

- Judging fitness for flight is a vital self-evaluation/assessment that every pilot (and their passengers) must conduct before any flight operation.

- Checklists such as the "IM SAFE" and "PAVE" checklists provide a self-check for a pilot's fitness to fly on any given day.

- Pilots must also consider the effects of perceived pressures, which lead to hazardous attitudes.

- While checklists help pilots stay safe and legal, everyone is different, emphasizing the importance of setting personal minimums.

- Think you've got a solid understanding of fitness for flight? Don't miss the fitness for flight quiz below and the topic summary.

Fitness for Flight Explained

- Fitness for flight is nothing more than a determination of readiness to fly.

- It is often subjective, but Tom Hoffmann boils it down to three fundamental questions in his FAA Safety Briefing article:

- Am I healthy?

- Am I legal?

- Am I proficient?

- Pilots have the responsibility to self-assess their abilities before each flight, made more manageable through checklists such as:

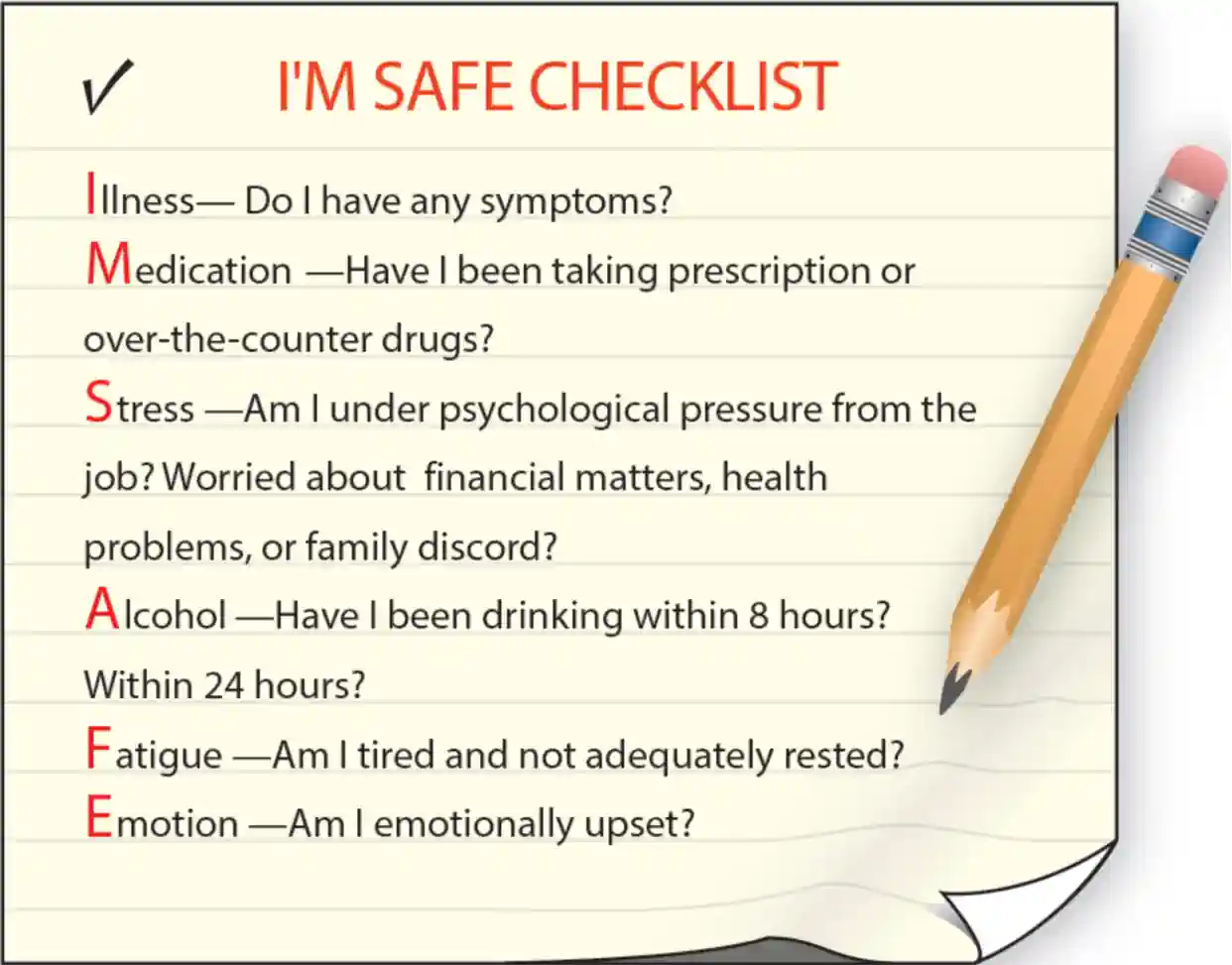

"IM SAFE" Checklist

- The IM-SAFE checklist requires pilots to assess themselves for any of these factors, individually or in combination, as they can significantly degrade decision-making and flying abilities.

- Illness: Do I have any symptoms?

- Medication: Have I been taking over-the-counter prescription drugs?

- Stress: Am I under psychological pressure from the job? Do I have money, health, or family problems?

- Alcohol: Have I been drinking within 8 hours? Within 24 hours?

- Fatigue: Am I tired and not getting enough rest?

- Eating/Emotion: Have I eaten enough of the proper foods to stay adequately nourished during the entire flight? Is my head in the right place?

-

Illness:

- Even a minor illness experienced in day-to-day living can significantly impair the performance of many piloting tasks vital to safe flight.

- Illness can produce fever and distracting symptoms that can impair judgment, memory, alertness, and the ability to make calculations.

- Although medication may control illness symptoms, it may also decrease pilot performance.

- Furthermore, FAR 61.53 prohibits a pilot from operating an aircraft if they are aware of a medical condition that would render them unable to meet the requirements for the medical certificate necessary for the pilot's operation, or, for those not requiring medical certification, make them unable to operate an aircraft safely.

- Sinus block can seriously damage the ears and nasal passages (and could lead to medical complications).

- Pilots should not fly until free from all illness.

- The pilot should contact an Aviation Medical Examiner for any further advice.

-

Motion Sickness:

- Both the FAA and AOPA offer several tips to minimize the effects of motion sickness:

- Before the flight, eat just a light meal a few hours before takeoff.

- Avoid smoking.

- If it's a training flight, be aware of the planned maneuvers for the lesson so you won't be surprised by "unusual attitude" training. If it's an aerobatics lesson, it's even more important to know the plan.

- Be relaxed with your instructor. Get it to a personal level so that there is a level of trust and good communication before you get to the airplane.

- During the flight, stay focused on the tasks, especially that of maintaining a straight and level attitude.

- If able to pass the controls to another pilot, focus on a point in the distance and avoid unnecessary head movements.

- Keep the vents open to allow fresh, cool outside air to circulate.

- Use supplemental oxygen if it is available.

- Both the FAA and AOPA offer several tips to minimize the effects of motion sickness:

-

Medications:

- Both prescribed and over-the-counter medications, along with the underlying medical condition, can significantly impair pilot performance.

- Many medications, such as tranquilizers, sedatives, strong pain relievers, and cough-suppressant preparations, have primary effects that may impair judgment, memory, alertness, coordination, vision, and the ability to make calculations.

- Other medications, such as antihistamines, blood pressure drugs, muscle relaxants, and agents for diarrhea or motion sickness, can impair the same critical functions through their side effects.

- Any medication that depresses the nervous system, such as a sedative, tranquilizer, or antihistamine, can make a pilot much more susceptible to hypoxia.

- For aviation safety, airmen should not fly following the last dose of any of the medications below until a period of time has elapsed equal to:

- 5 times the maximum pharmacologic half-life of the medication; or.

- 5 times the maximum hour dose interval if pharmacologic half-life information is not available. For example, there is a 30-hour wait time for a medication that is taken every 4 to 6 hours (5 times 6).

- FAR 91.17 prohibits pilots from performing crewmember duties while using any medication that affects the faculties in any way contrary to safety.

- The safest rule is not to fly as a crewmember while taking any medication unless approved to do so by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

- The pilot should contact an Aviation Medical Examiner for any further advice.

- The FDA offers an online label repository, and the FAA provides a guide for aviation medical examiners for reference.

-

Stress:

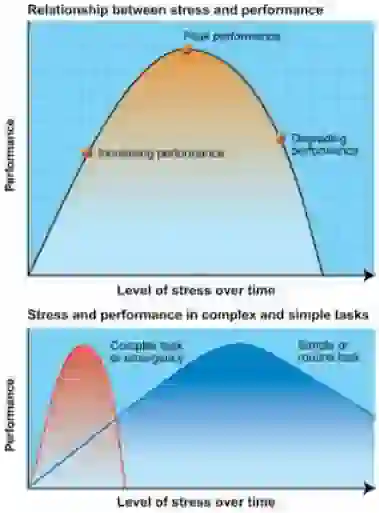

- Stress is the body's response to demands placed upon it. [Figure 1]

- The pressures of everyday living can occupy the thought process, subtly blocking alertness in the cockpit.

- Difficulties, particularly at work, can occupy one's thought processes to the extent that they markedly decrease alertness.

- Distraction can so interfere with a pilot's judgment that unwarranted risks are taken, for example, flying into deteriorating weather conditions to keep on schedule.

- Stress and fatigue (see below) can be an extremely hazardous combination.

- Initially, it can provide heightened awareness and an increase in performance.

- It is essential that when you reach your limit (which everyone has), you acknowledge it appropriately.

- Continuous stress additions will result in a decrease in performance, which interferes with a pilot's judgment and, therefore, leads to unwarranted risks.

- Most pilots carry stress into the cockpit, so when they face unusual difficulties, they should consider delaying the flight until they resolve those issues.

- Additionally, some in-flight occurrences can exacerbate the stress, creating an even more severe problem.

- Stress and fatigue can be a deadly combination.

- Indicators of excessive stress often show as:

- Emotional: denial, suspicion, paranoia, agitation, restlessness, or defensiveness.

- Physical: results in acute fatigue.

- Behavioral: sensitivity to criticism, tendency to be argumentative, arrogance, and hostility.

- Techniques that can help reduce stress:

- Become knowledgeable about stress.

- Take a realistic self-assessment (See the Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge).

- Take a systematic approach to problem-solving.

- Develop a lifestyle that buffers against the effects of stress (exercise and eating right are key).

- Practice behavior management techniques.

- Establish and maintain a strong support network.

- Good flight deck stress management begins with good life stress management:

- Avoid situations that distract from flying the aircraft.

- Reduce flight deck workload to reduce stress levels.

- If a problem occurs, remain calm.

- Become thoroughly familiar with the aircraft, its operation, and emergency procedures.

- Know and respect personal limits.

- If flying adds stress, consider either stopping flying or seeking professional help to manage stress within acceptable limits.

- Practice the 3Rs as outlined by Kenneth Stahl, MD, FACS, who writes in AOPA:

- First, resist the temptation to act on your first impulse and make a caveman response.

- Second, relax and take a huge, deep breath to utilize physiology in your favor and flush the acute stress chemicals from your bloodstream.

- Relax your muscles and roll your eyes back to induce slow beta-wave electrical activity.

- Third, reassess and refresh the decision-making process as the acute stress reaction clears and reassess options; use knowledge and training, not fight or flight reflexes, to solve the crisis."

-

Alcohol:

- Extensive research has provided several facts about the hazards of alcohol (and drugs) consumption and flying:

- As little as one ounce of liquor, one bottle of beer, or four ounces of wine can impair flying skills, with the alcohol consumed in these drinks being detectable in the breath and blood for at least 3 hours.

- Even after the body completely metabolizes a moderate amount of alcohol, a pilot can still be severely impaired for many hours by a hangover.

- There is no way to reduce the destruction of alcohol or alleviate a hangover.

- Alcohol renders a pilot much more susceptible to disorientation and hypoxia.

- A consistently high alcohol-related fatal aircraft accident rate serves to emphasize that alcohol and flying are a potentially lethal combination.

- FAR 91.17 prohibits pilots and remote pilots from performing crewmember duties:

- For at least 8 hrs after the last drink ("bottle to throttle").

- While under the influence of alcohol (possibly for more than 8 hours).

- While having an alcohol concentration of 0.04 or greater in the blood or breath specimen.

- Concentration means grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood or grams per 210 liters of breath.

- Therefore, a good rule of thumb is to allow at least 12 to 24 hours between "bottle and throttle," depending on the amount of alcoholic beverage consumed.

- Except in an emergency, a pilot of a civil aircraft may not carry anyone who appears intoxicated or shows signs of drug influence, except for a medical patient under proper care.

A crew member shall:

- On request of a law enforcement officer, submit to a test to indicate alcohol concentration in the blood or breath.

- Furnish to the FAA or Administrator, upon their request, the results or authorize the release of tests taken within 4 hours after acting or attempting to act as a crew member that indicates an alcohol/drug concentration in the blood or breath specimen.

- Any test information obtained by the FAA per the above may be evaluated in determining a person's qualifications for any airman certificate or possible violations of this chapter and may be used as evidence in any legal proceeding under sections 602, 609, or 901 of the Federal Aviation Act of 1958.

- Unless authorized by a Federal or State statute or agency, no one may operate a manned or unmanned civil aircraft in the United States knowing it carries narcotics, marijuana, or other depressant or stimulant substances defined by law.

- Under 14 CFR 61.15, all pilots must send a Notification Letter (MS Word) to the FAA's Security and Investigations Division within 60 calendar days of the effective date of an alcohol-related conviction or administrative action.

- This regulation does not apply to remote pilot certificates with a small UAS rating.

- Read more at the FAA's Airmen DUI/DWI page or at flightphysical.com.

- A conviction for the violation of any Federal or State statute relating to the growing, processing, manufacturing, sale, disposition, possession, transportation, or importation of narcotic drugs, marijuana, or depressant or stimulant drugs or substances is grounds for:

- Denial of an application for a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating for a period of up to 1 year after the date of final conviction; or.

- Suspension or revocation of a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating.

- Committing an act prohibited by FAR 91.17(a) or 91.19(a) is grounds for:

- Denial of an application for a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating for a period of up to 1 year after the date of that act; or.

- Suspension or revocation of a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating.

- o indicate the percentage by weight of alcohol in the blood, when requested by a law enforcement officer per §91.17(c) of this chapter, or a refusal to furnish or authorize the release of the test results ordered by the Administrator per FAR 91.17(c) or (d) of this chapter, is grounds for:

- Denial of an application for a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating for a period of up to 1 year after the date of that refusal; or.

- Suspension or revocation of a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating.

- For more information, read: alcohol and flying.

- Extensive research has provided several facts about the hazards of alcohol (and drugs) consumption and flying:

-

Fatigue:

- Fatigue remains one of the most treacherous hazards to flight safety, as it may not be apparent to a pilot until serious errors have already occurred.

- There are no real ways to measure your level of fatigue.

- Fatigue produces a decline in a variety of measures of performance similar to the effects of alcohol intoxication and other substances that affect mentation.

- High-level mental activities such as complex decision-making and planning suffer the most, whereas simple, well-practiced skills are less sensitive to fatigue.

- Described as either acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term).

-

Acute Fatigue:

- Regular occurrence of everyday living.

- The tiredness felt from physical/mental strain, emotional pressure, immobility/monotony, and lack of sleep.

- Acute fatigue can significantly reduce coordination and alertness.

- Adequate rest, regular exercise, and proper nutrition prevent acute fatigue.

- Consequently, coordination and alertness, so vital to safe pilot performance, can be reduced.

- Signs of acute fatigue:

- Misplacing items during the preflight.

- Leaving material (pencils, charts in the planning area.

- Missing radio calls.

- Answering calls improperly (read-backs).

- Improper tuning of frequencies.

- Pilots can prevent acute fatigue by getting adequate rest and sleep, exercising regularly, and maintaining a balanced diet.

-

Chronic Fatigue:

- It occurs when there is not enough time for full recovery between periods of acute fatigue.

- The pilot's performance continues to decline, and their judgment becomes impaired, leading to unwarranted risks.

- The underlying cause is generally not related to rest and may have more profound origins.

- Chronic fatigue is a combination of both physiological problems and psychological issues.

- Financial, home life, or job-related stress can lead to chronic fatigue.

- Recovery from chronic fatigue requires a prolonged period of rest.

-

Circadian Rhythms:

- Sleep is the body's mechanism for restoring the fatigued brain to peak energy and performance.

- Sleep architecture is complex and consists of different stages of activity (REM and non-REM sleep).

- Sleep needs are genetically determined; most people require 7 to 9 hours of sleep/night.

- Circadian ("about-a-day") rhythms govern all bodily activities, synchronized with daytime light exposure and activity levels.

- Circadian rhythms control sleep induction, maintenance, and termination.

- The effect of the alerting circadian rhythm is to boost the brain's alertness during the day, while fatigue accumulates and induces sleep at night, allowing the brain to recover.

- Shifts in time zones will disrupt circadian rhythms and require a varying time to resynchronize.

- During this disruption, fatigue levels will be unpredictable, with sleep efficiency and performance degrading to some degree.

-

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA):

- OSA is an important preventable factor identified in transportation accidents.

- OSA interrupts the regular restorative sleep necessary for normal functioning and is associated with chronic illnesses such as hypertension, heart attack, stroke, obesity, and diabetes.

- Symptoms include snoring, excessive daytime sleepiness, intermittent prolonged breathing pauses during sleep, memory impairment, and difficulty concentrating.

- Many available treatments can help reverse daytime symptoms and reduce the risk of an accident, and most are acceptable for medical certification upon demonstrating effectiveness.

- Suppose you have any symptoms described above, or a neck size over 17 inches in men or 16 inches in women, or a body mass index greater than 30. In that case, you should be evaluated for sleep apnea by a sleep medicine specialist (https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/ bmi/adult_bmi/english_bmi_calculator/bmi_calculator.html).

- With treatment, you can avoid or delay the onset of these chronic illnesses and prolong your quality of life.

-

-

Operational Limitations:

- Hours of training: In any 24 hours, a flight instructor may not conduct more than 8 hours of flight training.

-

Emotion:

- Similar to stress-type indications.

- Upsetting events such as a serious argument, a death, a breakup, a job loss, or a financial catastrophe can lead to risks that render a pilot unable to fly an aircraft safely.

- The emotions of anger, depression, and anxiety from such events not only decrease alertness but also may lead to taking risks that border on self-destruction.

- Pilots experiencing an emotionally upsetting event should not fly until they have satisfactorily recovered from it.

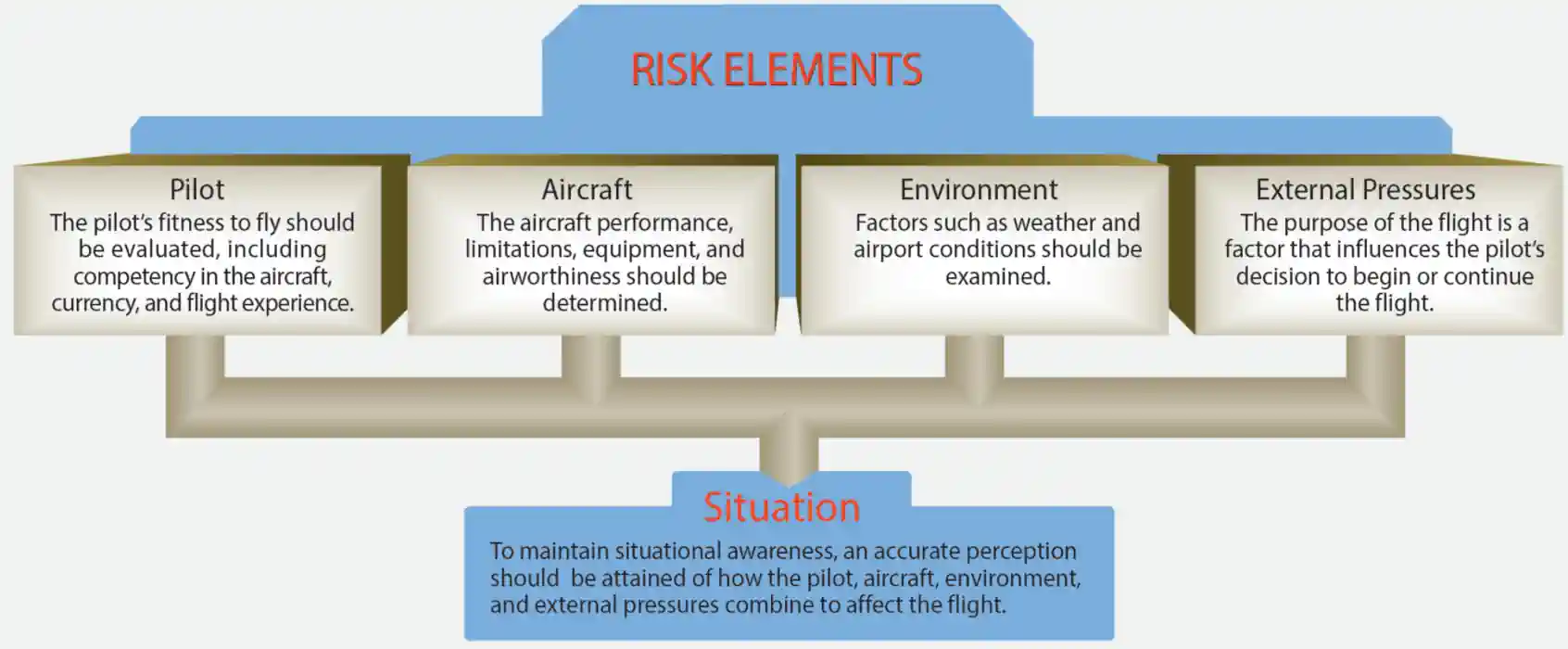

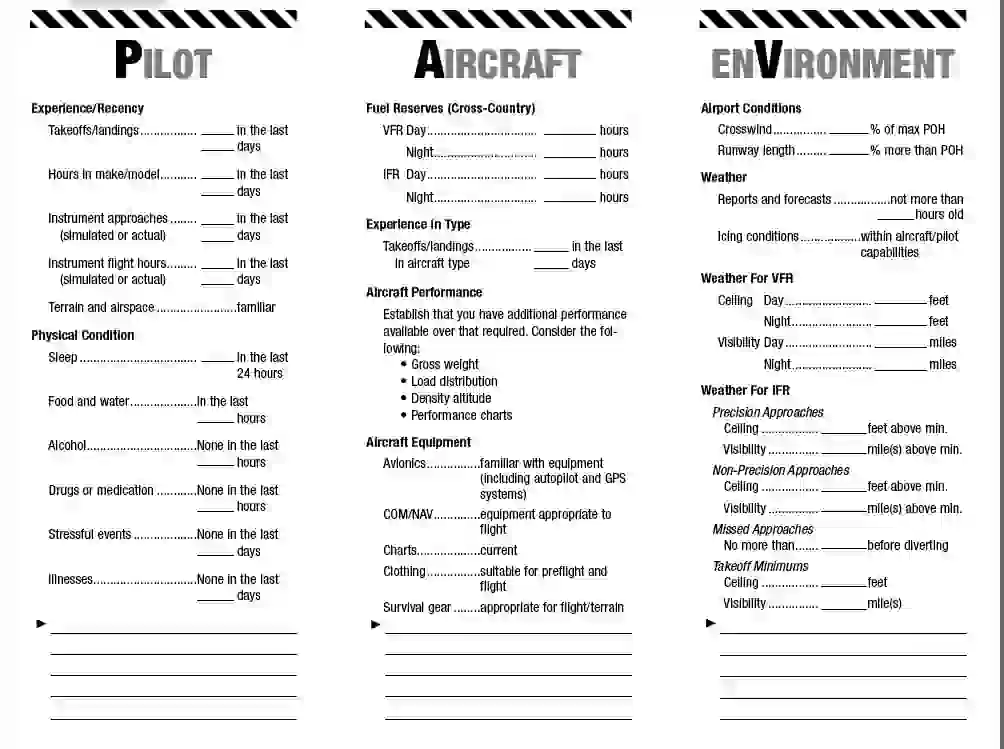

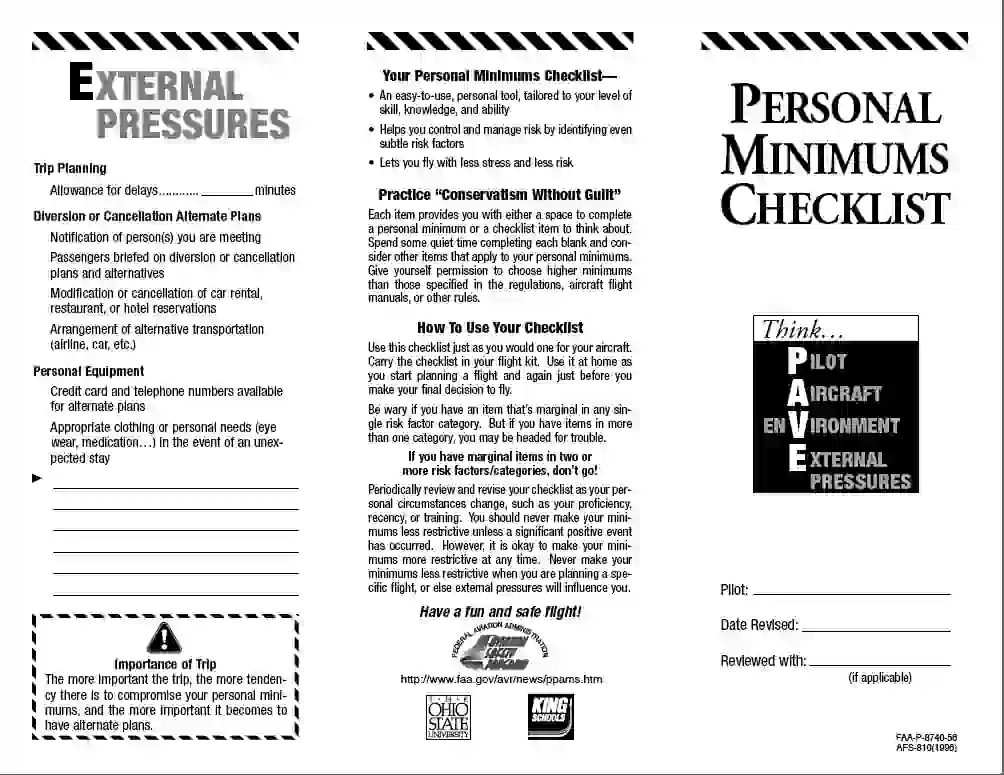

PAVE Checklist

- The PAVE checklist enhances situational awareness by categorizing risk in all stages of flight into four key areas: Pilot-in-Command, Aircraft, EnVironment, and External Pressures.

- With the PAVE checklist, pilots have a simple way to remember each category to examine for risk before each flight.

- All four elements combine and interact to create a unique situation for any flight.

- Once a pilot identifies a flight's risks, they must decide whether they can manage the risk safely and successfully.

- If not, choose to cancel the flight.

- If the pilot decides to continue the flight, they should develop strategies to mitigate the risks.

-

Step 1: P = Pilot-in-Command (PIC):

- The pilot is one of the risk factors in a flight.

- When considering that risk, a pilot may ask, "Am I ready for this trip?" in terms of experience, currency, and physical and emotional condition.

- The IMSAFE checklist, combined with proficiency, recency, and currency, helps provide the answer.

- Pilots should ask:

- Is the aircraft I will fly capable and equipped to complete this trip?

- Did the maintenance history indicate the aircraft is airworthy?

- Did my preflight inspection reveal any issues with the aircraft?

- Is there enough fuel onboard?

- Pilot-in-Command Risk Example:

- The Aircraft Flight Manual (AFM) lists the aircraft's maximum crosswind component as 15 knots, and the pilot has experience handling 10 knots of direct crosswind.

- It may be unsafe to exceed a 10 knot crosswind component without additional training.

- Therefore, the 10 knots crosswind experience level should be that pilot's personal limitation until additional training with a flight instructor provides the pilot with additional experience for flying in crosswinds that exceed 10 knots.

-

Step 2: A = Aircraft:

- What limitations will the aircraft impose upon the trip?

- Pilots should ask:

- Is this the right aircraft for the flight?

- Am I familiar with and up-to-date on this aircraft? Aircraft performance figures and the AFM assume a brand-new aircraft flown by a professional test pilot. Keep that in mind while assessing personal and aircraft performance.

- Is this aircraft equipped for the flight? Instruments? Lights? Are navigation and communication equipment adequate?

- Is this aircraft capable of operating on the available runways for the trip while maintaining an adequate safety margin under the planned conditions?

- Can this aircraft carry the planned load?

- Can this aircraft operate at the altitudes needed for the trip?

- Does this aircraft have sufficient fuel capacity, including reserves, for the planned trip legs?

- Did the quantity of fuel delivered match the quantity ordered?

- Did the maintenance history indicate the aircraft is airworthy?

- Did my preflight inspection reveal any issues with the aircraft?

-

Step 3: V = EnVironment:

Weather:

- The weather is a major environmental consideration.

- It is a consideration of both aircraft limitations and the Pilot-in-Command's experience and ability.

- Pilots should ask:

- What is the current ceiling and visibility? In mountainous terrain, consider having higher minimums for ceiling and visibility, particularly if the terrain is unfamiliar.

- Consider the possibility that the weather may be different than the forecast. Have alternative plans and be prepared to divert if an unexpected change occurs.

- Consider the winds and the strength of the crosswind component.

- If flying in mountainous terrain, consider whether there are strong winds aloft. Strong winds in mountainous terrain can cause severe turbulence and downdrafts, posing a significant hazard to aircraft, even when no other significant weather is present.

- Are there any thunderstorms present or forecast?

- Is there any icing, current, or forecast if there are clouds? What is the temperature/dew point spread and the current temperature at altitude? Can a descent be made safely all along the route?

- If encountering icing conditions, is the pilot experienced in operating the aircraft's deicing or anti-icing equipment? Is this equipment in good working condition? For what icing conditions is the aircraft rated, if any?

- Can both the aircraft and I fly in the expected weather conditions?

- The weather is a major environmental consideration.

- Evaluation of terrain is another important component of analyzing the flight environment.

- To avoid terrain and obstacles, especially at night or in low visibility, determine safe altitudes in advance by using the altitudes shown on VFR and IFR charts during preflight planning.

- Use maximum elevation figures (MEFs) and other easily obtainable data to minimize the chances of an in-flight collision with terrain or obstacles.

-

Airport:

- What lighting options are available at the destination and alternative airports? VASI/PAPI or ILS glideslope guidance? Is the terminal airport equipped with them? Are they working? Will the pilot need to use the radio to activate the airport lights?

- Check the Notices to Airmen (NOTAM) for closed runways or airports. Look for runway or beacon lights out, nearby towers, and other hazards.

- Choose the flight route wisely. An engine failure gives the nearby airports supreme importance.

- Are there shorter or obstructed fields at the destination and/or alternate airports?

-

Airspace:

- If the trip involves traveling to remote areas, is there sufficient clothing, water, and survival gear onboard in the event of a forced landing?

- If the trip involves flying over water or unpopulated areas where the pilot might lose visual reference to the horizon, the pilot must prepare to fly IFR.

- Check the airspace and any temporary flight restrictions (TFRs) along the route of flight.

-

Night Flying:

- Night flying requires special consideration.

- If the trip involves flying over water or unpopulated areas with a chance of losing visual reference to the horizon, the pilot must prepare to fly IFR.

- Will the flight conditions allow a safe emergency landing at night?

- Before a night flight, check all aircraft lights, both interior and exterior.

- Carry at least two flashlights: one for exterior preflight and a smaller, dimmable one for interior use.

-

Step 4: E = External Pressures:

- External pressures are external influences that create a sense of pressure to complete a flight, often at the expense of safety.

- Factors that can be external pressures include the following:

- Someone is waiting at the airport for the arrival of the flight.

- A passenger, the pilot, does not want to disappoint.

- The desire to demonstrate pilot qualifications.

- The desire to impress someone (Probably the two most dangerous words in aviation are "Watch this!").

- The desire to satisfy a specific personal goal ("get-home-itis," "get-there-itis," and "let's-go-itis").

- May manifest in the excitement of getting to a location like a fly-in.

- If the pilot has a time-sensitive reason to be somewhere, they should consider stopping near a commercial airport to travel safely and return to the aircraft easily.

- The pilot's general goal-completion orientation.

- Emotional pressure is associated with acknowledging that skill and experience levels may be lower than a pilot would like them to be.

- Pride can be a decisive external factor.

- Managing External Pressures:

- Management of external pressure is the most critical key to risk management because it is the one risk factor category that can cause a pilot to ignore all the other risk factors.

- External pressures put time-related pressure on the pilot and figure into most accidents.

- Using personal standard operating procedures (SOPs) is one way to manage external pressures.

- The goal is to supply a release for the external pressures of a flight.

- These procedures include, but are not limited to:

- Allow time on a trip for an extra fuel stop or to make an unexpected landing due to weather conditions.

- Have alternate plans for late arrival or make backup airline reservations for must-be-there trips.

- For essential trips, plan to leave early enough to allow for a smooth drive to the destination, if necessary.

- Be aware of and advise those waiting at the destination of any delays.

- Manage passengers' expectations. Ensure passengers are aware that they may not arrive on a firm schedule. If they must arrive by a specific time, they should make alternative arrangements.

- Eliminate pressure to return home, even on a casual day flight, by carrying a small overnight kit containing prescriptions, contact lens solutions, toiletries, or other necessities on every flight.

- Management of external pressure is the most critical key to risk management because it is the one risk factor category that can cause a pilot to ignore all the other risk factors.

- Pilots should ask:

- Does this flight have to be completed today?

- Are peers or passengers pressuring me to fly?

- Do I have any commitments after the flight that I need to attend to?

- Do I feel pressured or rushed to get to my destination?

- The key to managing external pressure is to be ready for and accept delays.

- Keep in mind that people often experience delays when traveling by air, driving, or taking a bus. The pilot's goal is to manage risk, not create hazards.

- Are We There Yet? explores further external pressures.

- Pay special attention to the pilot aircraft combination, and consider whether the combined "pilot-aircraft team" is capable of the mission you want to fly.

- The FAA offers a safety brochure to help pilots develop their personal minimums.

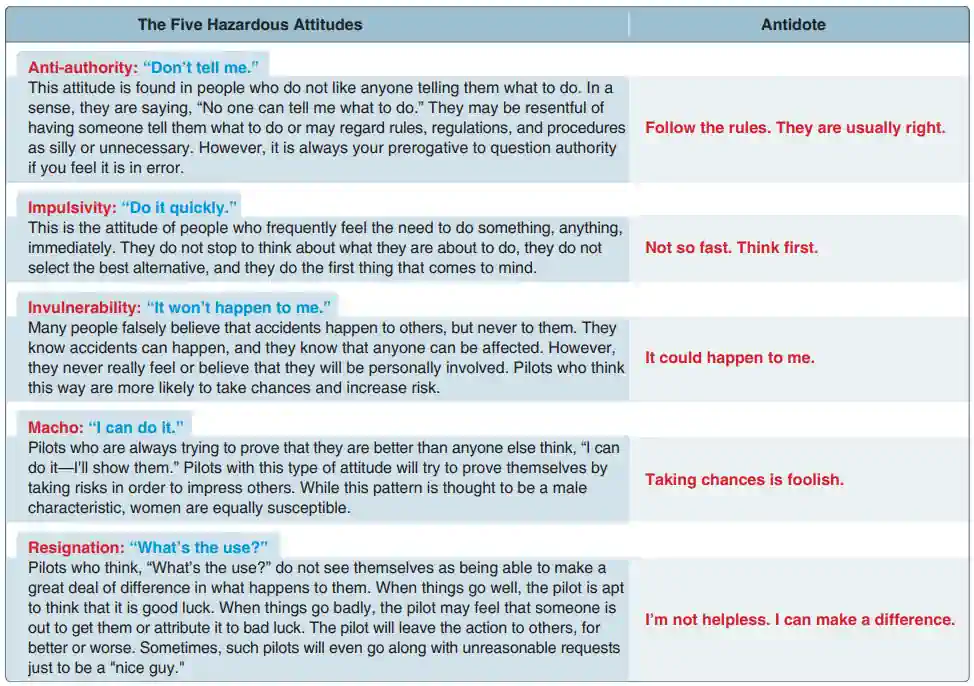

Hazardous Attitudes

- Being fit to fly depends on more than just a pilot's physical condition and recent experience.

- Studies have identified five hazardous attitudes that can interfere with the ability to make sound decisions and exercise authority effectively: anti-authority, impulsivity, invulnerability, machismo (also known as "macho"), and resignation.

- Hazardous attitudes, which contribute to poor pilot judgment, are dangerous personalities we must learn to recognize within ourselves and others.

- A pilot who exhibits a hazardous trait may not recognize it themselves, and it may be up to you to prevent a catastrophe.

- Early recognition of these hazardous attitudes allows you to take proper corrective action. [Figure 4]

- A pilot who will risk their own life will likely do the same with their passengers!

- Research (which later evolved into the Crew Resource Management concept) has identified five overarching hazardous attitudes that can affect a pilot's judgment, as well as the corresponding antidotes for each.

-

Impulsivity:

- "Do it quickly."

- The attitude of people who frequently feel the need to do something, anything, immediately demonstrates impulsivity.

- They do not stop to think about what they are about to do; they do not select the best alternative and do the first thing that comes to mind.

-

Invulnerability:

- "It won't happen to me."

- Many people feel that accidents happen to others but never to them.

- They recognize that accidents can occur and can impact anyone.

- Still, they never really feel or believe that they will be personally involved.

- Experience can be a significant contributing factor.

- Pilots who think this way are more likely to take risks, which increases the likelihood of accidents.

-

Macho:

- "I can do it."

- Pilots who are always trying to prove that they are better than anyone else are thinking, "I can do it. I'll show them."

- Pilots with this type of attitude will try to prove themselves by taking risks to impress others.

- This pattern is assumed to be a male characteristic; however, women are equally susceptible.

-

Resignation:

- "What's the use?"

- Pilots feeling resignation do not see themselves as being able to make a great deal of difference in what happens to them.

- When things go well, the pilot is apt to attribute it to good luck.

- When things go badly, the pilot may feel that someone is out to get them or attribute it to bad luck.

- The pilot will leave the action to others, for better or worse.

- Sometimes, such pilots comply with unreasonable requests just to be perceived as a "nice guy."

Setting Personal Minimums

- Every pilot must know their limits.

- Failing to recognize your limits can result in an inability to manage risk appropriately, leading to a mishap.

- You must evaluate fitness for flight based on the specific circumstances of that flight.

- Accordingly, those requirements to consider a pilot "fit to fly" may change.

- Exceeding one's comfort zone is based on factors such as operation, currency, proficiency, and weather, among others.

- Treat every flight as if it were your first solo, and apply that level of thought and concentration where applicable.

- The AOPA offers a guide/checklist to write down VFR and/or IFR minimums.

- The FAA breaks down the development of personal minimums into six steps:

-

Step 1 - Review Weather Minimums:

- Given the current weather forecasts, will the flight be conducted under VFR, MVFR, IFR, or LIFR conditions?

-

Step 2 - Assess Your Experience and Comfort Level:

- Given recent flights, are you comfortable with the current weather conditions?

-

Step 3 - Consider Other Conditions:

- Besides weather, what other environmental factors might be at hand, including winds, temperatures, and short runways?

-

Step 4 – Assemble and Evaluate:

- Given the conditions identified in steps 1 through 3, where do you personally draw the line?

-

Step 5 – Adjust for Specific Conditions:

- Consider developing a chart of adjustment factors based on changes in the PAVE checklist factors: Pilot, Aircraft, EnVironment, and External Pressures.

- What is the maximum wind you're comfortable with? Does it change with aircraft? Are certain airports different than others, and if so, with what regard?

- Note that:

- Never adjust personal minimums to a lower value for a specific flight:

- The time to consider changes is when you are not under pressure to fly and have the time and objectivity to think honestly about your skills, performance, and comfort level.

- Keep all other variables constant:

- If your goal is to lower your baseline personal minimums for visibility, don't try to reduce the ceiling, wind, or other values simultaneously.

- Never adjust personal minimums to a lower value for a specific flight:

-

Step 6 – Stick to the Plan!

- Once you have established baseline personal minimums, "all" you need to do next is stick to the plan.

-

Private Pilot (Airplane) Human Factors Airman Certification Standards

- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with personal health, flight physiology, and aeromedical and human factors related to the safety of flight.

- References: AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8083-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge).

- Private Pilot (Airplane) Human Factors Lesson Plan

Private Pilot (Airplane) Human Factors Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

PA.I.H.K1:

Symptoms, recognition, causes, effects, and corrective actions associated with aeromedical and physiological issues, including:-

PA.I.H.K1a:

Hypoxia. -

PA.I.H.K1b:

Hyperventilation. -

PA.I.H.K1c:

Middle ear and sinus problems. -

PA.I.H.K1d:

Spatial Disorientation. -

PA.I.H.K1e:

Motion sickness. -

PA.I.H.K1f:

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. -

PA.I.H.K1g:

Stress. -

PA.I.H.K1h:

Fatigue. -

PA.I.H.K1i:

Dehydration and nutrition. -

PA.I.H.K1j:

Hypothermia. -

PA.I.H.K1k:

Optical Illusions. -

PA.I.H.K1l:

Dissolved nitrogen in the bloodstream after scuba dives.

-

-

PA.I.H.K2:

Regulations regarding the use of alcohol and drugs. -

PA.I.H.K3:

Effects of alcohol, drugs, and over-the-counter medications. -

PA.I.H.K4:

Aeronautical Decision-Making (ADM) to include using Crew Resource Management (CRM) or Single-Pilot Resource Management (SRM), as appropriate.

Private Pilot (Airplane) Human Factors Risk Management:

The applicant demonstrates the ability to identify, assess, and mitigate risks encompassing:-

PA.I.H.R1:

Aeromedical and physiological issues. -

PA.I.H.R2:

Hazardous attitudes. -

PA.I.H.R3:

Distractions, task prioritization, loss of situational awareness, or disorientation. -

PA.I.H.R4:

Confirmation and expectation bias.

Private Pilot (Airplane) Human Factors Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

PA.I.H.S1:

Associate the symptoms and effects for at least three of the conditions listed in K1a through K1l above with the cause(s) and corrective action(s). -

PA.I.H.S2:

Perform self-assessment, including fitness for flight and personal minimums, for actual flight or a scenario given by the evaluator.

Fitness for Flight Lessons & Case Studies

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: MIA94FA148:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot's impairment of judgment and performance due to alcohol and drugs, which led to his improper planning/decision, and his failure to maintain adequate airspeed during a maneuver.

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: CEN12FA571:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The student pilot's impairment from alcohol, marijuana, and hypoxia, which adversely affected his ability to maintain control of the airplane.

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: CEN21LA089:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The student pilot's decision to conduct a flight during night instrument meteorological conditions and his loss of airplane control due to spatial disorientation. Contributing to the accident was the student pilot's use of an amphetamine and his attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: ERA17FA180:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The noninstrument-rated pilot's intentional visual flight rules flight into instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in a loss of airplane control due to spatial disorientation. Contributing to the accident was the pilot's overreliance on his limited instrument training.

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: CEN14FA042:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: A loss of control due to spatial disorientation. Contributing to the accident were the private pilot's impairment due to a sedating antihistamine and both pilots' fatigue.

Fitness for Flight Knowledge Quiz

Fitness for Flight Conclusion

- Determining fitness for flight is just one measure pilots take to approach safety proactively.

- The most critical skill a pilot builds is deciding when not to fly.

- In addition to obtaining a medical certificate determining overall fitness for flight, it is a vital self-evaluation that every pilot (and their passengers) must conduct before any flight operation.

- Aircraft accident statistics indicate that pilots should conduct preflight checklists on themselves as well as their aircraft, as pilot impairment contributes to a significantly higher number of accidents than failures of aircraft systems.

- These Physiological and psychological factors can affect a pilot and compromise the safety of a flight.

- Practical fitness for flight determinations are the first link in the chain of events that, if ignored, could lead to a mishap.

- While the IM SAFE and PAVE checklists exist to help, they're interrelated topics and only a checklist for a holistic fitness determination.

- Fatigue is significant enough for the FAA to have published Advisory Circular (120-100) Basics of Aviation Fatigue.

- Be cautious of the effects of coffee and energy drinks, which can make you feel alert but may not reduce fatigue.

- Personal minimums are established over time and set before the flight.

- It is acceptable to have different minimums for each flight, based on factors such as confidence in the route, recent training, or lack thereof, for both pilots.

- Review personal minimums/decision making with the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association safety spotlight, Doing the Right Thing: Decision Making for Pilots.

- Aircraft accident statistics indicate that pilots should conduct preflight checklists on themselves as well as their aircraft, as pilot impairment contributes to a significantly higher number of accidents than failures of aircraft systems.

- The IM SAFE checklist is your last line of defense in determining if you are mentally and physically fit to conduct the flight.

- One of the most important concepts that safe pilots understand is the difference between what is "legal" in terms of the regulations and what is "smart" or "safe" in terms of pilot experience and proficiency (currency versus proficiency).

- Still looking for something? Continue searching:

Fitness for Flight References

- Aeronautical Information Manual (8-1-1) Fitness For Flight

- AOPA - Ear, Nose, Throat, and Equilibrium, Motion Sickness

- AOPA Air Safety Institute - IFR Personal Minimums Contract

- AOPA - Ounce of Prevention Part 11 of 12: Preflight Yourself, Then Your Airplane

- AOPA - Stress: Not Just for Wing Loads- Part One

- AOPA Air Safety Institute - VFR Personal Minimums Contract

- Federal Aviation Administration - Are You Fit for Flight?

- Federal Administration Medium - Misfortune with Medications

- Federal Aviation Administration - Getting the Maximum from Personal Minimums

- Federal Aviation Administration - Industry Training Standards Personal and Weather Risk Assessment Guide

- Personal Minimums Worksheet

- Federal Aviation Administration - Motion Sickness and Aviation

- Federal Aviation Administration - Medications and Flying

- Federal Aviation Administration - Personal Minimums

- Federal Aviation Administration - Pilots and Medication

- Federal Aviation Administration - Pilot/Controller Glossary

- Federal Aviation Administration - Personal Minimums Checklist

- Federal Aviation Regulations (91.17) Alcohol or drugs

- Flight Physical.com - Alcohol and Flying

- Instrument Flying Handbook (1-11) Physiological and Psychological Factors

- Moroccan Air Line Pilots Association - I.M S.A.F.E. Checklist

- NIH - How Much Sleep Is Enough?