Aerodynamics & Performance

Aerodynamics is the branch of dynamics dealing with the motion of air and other gases that provide the performance aircraft need to fly.

Introduction to Aerodynamics & Performance

- Aerodynamics is the branch of dynamics dealing with the motion of air and other gases, which gives us the performance we need to fly.

- Understanding basic aerodynamic concepts is crucial for comprehending the operation of an aircraft's components and subcomponents.

- The principal aerodynamic concepts are those of the four forces that affect aircraft.

- It can be associated with the forces acting on an object in motion through the air or with a stationary object in a current of air.

- Several factors affect aircraft performance, including the atmosphere, aerodynamics, and aircraft icing.

- Pilots need an understanding of these factors to provide a sound basis for anticipating aircraft response to control inputs, which come in the form of performance.

Lift & Basic Aerodynamics

- Aircraft components and structure create the physical form we know as an aircraft.

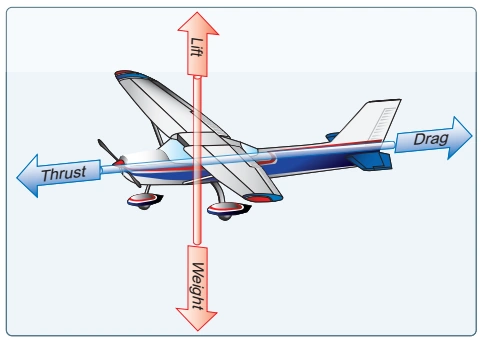

- Four forces act upon an aircraft, making up the Principles of Flight.

- Understanding how these forces are created and, more importantly, how they interact with each other enables pilots to control an aircraft in flight.

- These principal forces are thrust, drag, weight, and lift: [Figure 1]

-

Thrust:

- Thrust is the forward force produced by the powerplant/propeller.

- It opposes or overcomes the force of drag.

-

Drag:

- Drag is a rearward, retarding force caused by the disruption of airflow by the wing, fuselage, and other protruding objects.

- Drag opposes thrust and acts rearward parallel to the relative wind.

-

Weight:

- Weight is the combined load of the aircraft itself, the crew, the fuel, and the cargo or baggage.

- The weight pulls the aircraft downward because of the force of gravity.

-

Lift:

- Lift opposes the downward force of weight, produced by the dynamic effect of the air acting on the wing, and acts perpendicular to the flight path through the wing's center of lift (CL).

-

- Engineers design aircraft with different handling characteristics in mind, which determine aircraft stability.

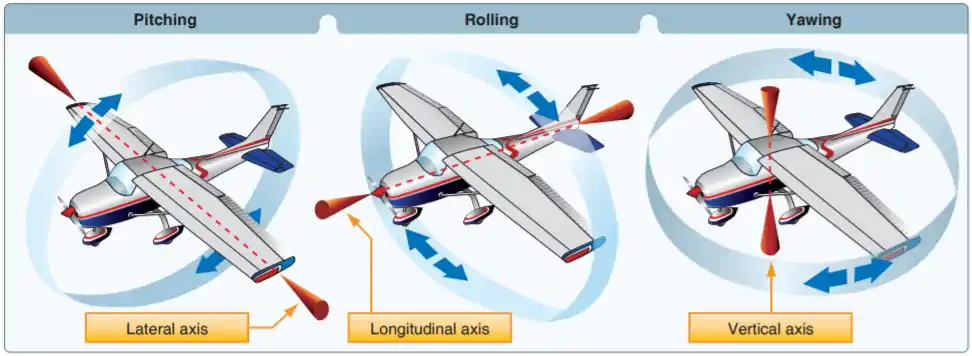

- An aircraft moves in three dimensions and is controlled by moving it about one or more of its axes:

- The longitudinal, or roll, axis extends through the aircraft from nose to tail, with the line passing through the center of gravity.

- The lateral or pitch axis extends across the aircraft on a line through the wing tips, again passing through the center of gravity.

- The vertical, or yaw, axis passes through the aircraft vertically, intersecting the center of gravity.

- All control movements cause the aircraft to move around one or more of these axes, enabling control of the aircraft in flight. [Figure 3]

- Aircraft performance designs are dependent upon operating within weight and balance limitations.

- NASA - Aerodynamics Index

Aircraft Performance

- The performance or operational information section of the Aircraft Flight Manual/Pilot's Operating Handbook (AFM/POH) contains the aircraft's takeoff, climb, range, endurance, descent, and landing data.

- Using this data in flying operations is mandatory for safe and efficient operation.

-

Stall Performance:

- Stalls are an aerodynamic condition whereby air can no longer smoothly flow over an airfoil, resulting in a rapid loss of lift.

- Stalls are ultimately brought on by exceeding the critical angle of attack.

- A stall is, therefore, an aerodynamic condition in which the Angle of Attack (AoA) becomes so steep that air can no longer flow smoothly over the airfoil.

- Said another way, a stall is a condition of flight in which an increase in AoA results in a decrease in lift.

- Angle of Attack (AoA/Alpha): the angle (in arbitrary units) between the relative wind and the chord line of an airfoil.

- Critical AoA: the angle of attack whereby any further increase will result in a separation of airflow, which results in a stall.

- An airfoil's ability to provide sufficient lift is dependent upon the load factor, that is, the amount of lift required to support the aircraft's load in flight.

- Load factor is not only dependent on the aircraft's weight that the wings must support, but also on the angle of bank, which contributes to the effective weight of the aircraft.

- Upon airflow separation from the wing, the airfoil will no longer produce lift.

- Angle of attack is an arbitrary measurement expressed in arbitrary units.

- Approaching the critical angle of attack, several indications of a stall will be present, warning pilots of pending danger.

- Although it is an abstract concept expressed in abstract units, several stall speed considerations are taken into account in aircraft design and performance envelopes to ensure the aircraft remains within the standard flight envelope.

- AOA enables pilots to recognize stalls before it's too late.

- Still, stall avoidance practices are critical.

- Notably, compressor stalls result from the same airfoil stall principles but are specific to turbine aircraft and generally not a factor when aircraft operate within their standard flight envelope.

-

Turn Performance:

- When an aircraft banks, the resultant lift splits between a vertical and horizontal component, providing the horizontal forces necessary to turn.

- We call this turn performance.

- Lift is a key principle of flight, essential to flight and, therefore, turn performance.

- When an aircraft banks, the lift vector of the aircraft rotates with it, producing a vertical and horizontal component.

- The relationship between the aircraft's speed and bank angle determines the rate and radius of turns.

- The bank angle, in conjunction with aircraft speed, forms a relationship between the rate of turn and radius of turn.

- The equal and opposite reaction to this sideways force is centrifugal force, which is merely an apparent force as a result of inertia.

- Pilots endeavor to maintain coordination throughout turns to avoid slipping/skidding.

- Understanding the rate, radius, and performance in a turn, aircraft performance while turning is more straightforward to comprehend.

- Pilots must be careful not to overanticipate or overcompensate, which can lead to overbanking in a turn.

- These principles are typically in reference to turns, but they are foundational to several maneuvers, including aerobatics.

- When an aircraft banks, the resultant lift splits between a vertical and horizontal component, providing the horizontal forces necessary to turn.

-

Takeoff & Climb Performance:

- Takeoff performance transitions the aircraft from the terminal to the enroute structure.

- Various factors impact takeoff distance.

- Pilots must calculate their takeoff distance according to several variables before flight to ensure adequate performance.

- It is essential to recognize that any calculated performance may differ from reality.

- Pilots evaluate climb performance to determine the appropriate parameters and procedures for safely and efficiently clearing obstacles and transitioning to the enroute environment.

-

Cruise Performance:

- Cruise is the predominant phase of flight by time, making cruise performance one of the most influential factors on the duration and quality of a flight.

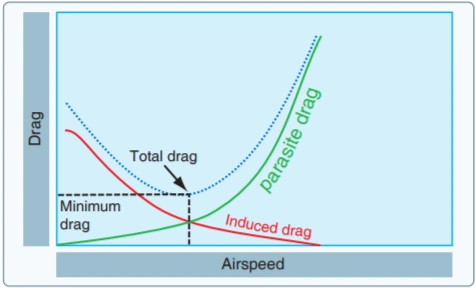

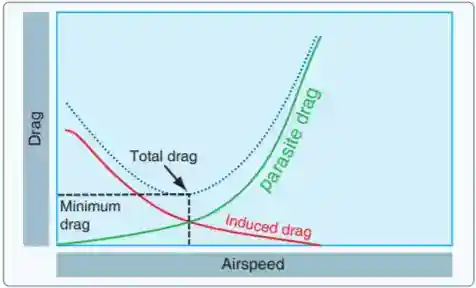

- With an appreciation of the drag curve, pilots configure and fly the aircraft to achieve maximum range or maximum endurance.

- Pilots must also consider how various factors impact cruise performance to plan for expected performance.

- Expected conditions necessitate pilot actions, such as applying maneuvering speed to cruise.

-

Descent and Landing Performance:

- Expected descent and landing performance drives airfield suitability decisions and impacts the conduct of the approach and landing.

- Landing performance starts with the descent.

- Landing distance depends on several factors, most of which are based on engineering data and can be determined by referencing performance charts.

- There are, of course, variables that must be considered, such as:

- Flight profile flown.

- Temperature.

- Field elevation/altitude.

- Winds.

- Runway slope.

- Runway surface condition, including hydroplaning.

- Balancing all these variables yields a series of best practices for landing performance.

- Still, the pilot can affect performance through techniques such as slips to landing, whether it is through forward or side slips.

- Finally, the approach determines the descent rate.

-

Glide Performance:

- Expected Glide Performance drives airfield suitability decisions and impacts the conduct of the approach and landing.

- Ultimately, glide performance translates into options for gliders or aircraft in the event of an engine-out situation.

- Expected Glide Performance drives airfield suitability decisions and impacts the conduct of the approach and landing.

-

Effects of Atmospherics:

- Atmospherics have both positive and negative impacts on how an aircraft performs.

- Cold Temperature Operations

- Warm Temperature Operations

- To precisely calculate aircraft performance, pilots utilize charts, tables, and data such as those provided in the airplane flight manual.

Aircraft Performance Charts, Tables, & Data

- Performance Calculations.

- Manufacturers evaluate aircraft performance under specific conditions and later compile the results into performance charts.

- Pilots must reference these performance charts to calculate the anticipated performance for a given operation.

- Calculate the crosswind component for takeoff and landing.

- Calculating short-field takeoff and climb distance.

- Charts may list the conditions used to gather performance data; however, pilots generally fly using proper technique, under standard atmospheric conditions, to a level, dry, paved runway, and without wind.

- The difference between charted data and flown data becomes the difference between expected performance and actual performance.

- Note also that pilots alter the aircraft configuration according to the procedure (e.g., using flaps for a soft-field) to achieve different landing and takeoff performance.

- Different configurations, therefore, will achieve different performance; or, to put it differently, the required performance necessitates different configurations.

- Necessary climb performance calculations will depend on the situation, but include:

- Top-of-climb for flight planning.

- Climb gradients that ensure regulatory compliance.

- Rates of climb that determine expected performance.

Performance Calculations Versus Reality

- Charts contain performance data based on expected performance under specific conditions.

- In other words, pilot operating handbook numbers necessitate the use of the pilot operating handbook technique.

- The conditions present during calculation will always differ to some degree, and sometimes significantly, from those in the charts and graphs.

- Factors to consider include mechanical, environmental, skill, geographic location, and altitude.

- It is important to use conservative numbers.

- Consider always rounding up, rather than interpolating, and using the higher number, etc.

- Realize obstacles like trees may be more than 50'; therefore, charts are wholly inadequate to calculate by numbers.

- Consider adding 50-100% buffers to anything calculated and monitor performance while in flight.

- If numbers were overly conservative, adjust for subsequent flights.

Aerodynamics & Performance Conclusion

- Resources like Real Engineering - The Plane That Will Change Travel Forever effectively describe complex aerodynamic topics clearly and concisely.

- Consider actual versus realized performance when doing any performance calculations.

- Still looking for something? Continue searching: