Spatial Disorientation & Illusions in Flight

Spatial disorientation in aviation occurs when a pilot’s senses misinterpret aircraft position or motion, leading to dangerous illusions that can cause loss of control if not corrected.

Introduction to Spatial Disorientation & Illusions in Flight

- Sensory mismatches can result in a pilot's loss of orientation to the surrounding environment, also known as spatial disorientation.

- Disturbances to sensory systems or the inaccurate perception of a given situation may produce several dangerous illusions in flight.

- Various sources and interpretations can cause pilots to experience in-flight illusions, which fall into four main categories: vestibular, visual, landing, and atmospheric.

- Vestibular system illusions consist of the inner ear's interpretation of orientation.

- Visual cues, supported by other senses, such as the vestibular system, are crucial metrics for maintaining spatial orientation.

- These cues are even more critical at night.

- Differences in runway size, width, and slope can also lead to illusions during landing.

- While many illusions are due to human limitations, atmospheric factors may also be at play.

- There are several steps pilots can take to prevent illusions from occurring; however, it is never possible to eliminate the risk.

- As such, pilots must be prepared to cope with spatial disorientation.

- Together, prevention and coping skills help mitigate dangerous outcomes from occurring.

- When you have a solid understanding of taxiing, compare your knowledge against the Private Pilot (Airplane) and Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Spatial Disorientation Airman Certification Standards.

- Once satisfied, close out with the topic summary and prepare for your next lesson.

Spatial Disorientation Overview

- The three-dimensional environment of flight is unfamiliar to our bodies, creating sensory conflicts and illusions that make spatial orientation difficult.

- Generally, pilots determine the flight attitude of an airplane by reference to the natural horizon.

- When atmospheric or lighting conditions obscure the natural horizon, attitude pilots can sometimes maintain reference to the surface below.

- If neither horizon nor surface references are available, the airplane's attitude must be determined using artificial means, such as an attitude indicator or other flight instruments.

- However, during periods of low visibility, the supporting senses sometimes conflict with what the pilot sees.

- When the sensory system doesn't agree with where you believe yourself to be in space, spatial disorientation has occurred.

- Becoming spatially disoriented is the result of a properly functioning human system, which we inherently trust, misinterpreting our actual position or orientation in space.

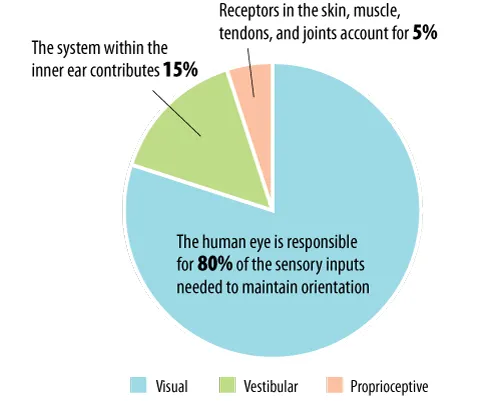

- Sensory inputs fall into three categories:

-

Visual Sensory Input:

- Visual cues are the most significant contributor to determining spatial orientation.

- The eye gathers visual sensory inputs through visual acuity (focus), depth perception, and orientation.

- Conditions that preclude the eye's ability to sense (such as clouds, darkness, and indistinct contrast between land and sky) will increase the chance of sensory mismatches and, therefore, spatial disorientation.

-

Vestibular Sensory Input:

- The vestibular system comprises the sensory organs located within the inner ear that detect the relative motion of the head in space along its axes of movement.

- It consists of two major components:

- Semicircular canals detect changes in rotational acceleration.

- The otolith organs detect linear (straight) acceleration.

- Accidents can occur due to a combination of vestibular illusions and poor visibility.

-

Proprioceptive Sensory Input:

- Proprioception is a term that encompasses the human sensation of the body's position.

- Proprioceptive sensory inputs provide us with a reference for posture and the relative position of our body in our environment.

-

Spatial Disorientation Risk Factors

- Age, fatigue, stress, anxiety, certain medical conditions, medications, smoking, alcohol, and other drugs that affect the visual, vestibular, or proprioceptive sensory inputs can also increase susceptibility.

- When visual cues are absent, your body will turn to your vestibular system for information.

- The complexity of the vestibular system makes it vulnerable to deception in certain flight conditions.

- When motion makes this system unreliable, pilots experience vestibular illusions. These dangerous illusions are the most likely culprits of spatial disorientation.

- As the body interprets various sensory inputs, mismatches can confuse the brain, manifesting in illusions in flight.

Illusions in Flight

-

Vestibular System Illusions:

- Vestibular system illusions are related to the inner ear.

- Inner-ear derived illusions include:

-

The Leans:

- If entering a turn too slowly to stimulate the motion-sensing system in the inner ear (less than 2°/second), an abrupt correction of a banked attitude can create the illusion of banking in the opposite direction. [Figure 1]

- The body never detected the turn in the first place, still feeling as though the aircraft/pilot's body is straight and level.

- When rolling back to level, the body may detect this movement as rolling from level to the side, rather than rolling back to level.

- If the pilot relies on what their body is telling them, the pilot might lean in the direction of the original turn to regain what they think is the correct vertical posture.

- The disoriented pilot will roll the aircraft back into its original attitude, or if level flight is maintained, will feel compelled to lean in the perceived vertical plane until this illusion subsides.

- Maintaining a good instrument scan allows the pilot to detect this sensory mismatch and maintain a level flight.

- A breakdown in the instrument scan will lead a pilot to believe the body's sensation and not recognize that the aircraft's attitude differs from expectations.

- Similarly, when entering a turn slowly and if an instrument scan is poor, a pilot may never detect the sensation of a turn.

- The pilot may not recognize what is happening until the aircraft is in an aggressive, unusual attitude.

- If entering a turn too slowly to stimulate the motion-sensing system in the inner ear (less than 2°/second), an abrupt correction of a banked attitude can create the illusion of banking in the opposite direction. [Figure 1]

-

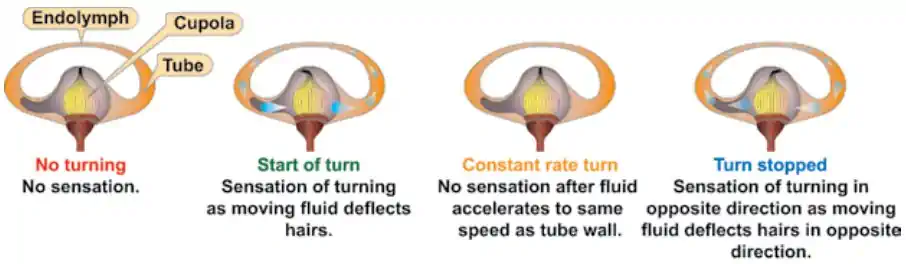

Coriolis illusion:

- The Coriolis illusion occurs when a pilot has been turning long enough for the fluid in the ear canal to move at the same speed as the canal, followed by an abrupt head movement.

- A movement of the head in a different plane, such as looking at something in a different part of the flight deck or grabbing a chart, may set the fluid moving and create the illusion of turning or accelerating on an entirely different axis.

- The disoriented pilot may maneuver the aircraft into a dangerous attitude in an attempt to correct the aircraft's perceived attitude.

- Pilots must develop an instrument cross-check or scan that involves minimal head movement.

- Always avoid abrupt maneuvers with your head, especially at night or in instrument conditions, while making prolonged, constant-rate turns.

-

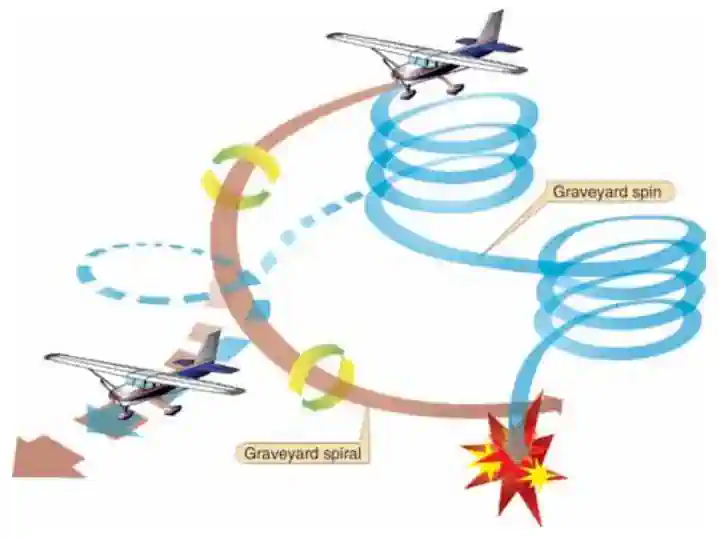

Graveyard Spin:

- Proper recovery from spin stops stimulating the motion system.

- An abrupt stop can stimulate a spin in the opposite direction. [Figure 2]

- Pilot corrections for this illusion could return the aircraft to the original spin.

- Proper recovery from spin stops stimulating the motion system.

-

Graveyard Spiral:

- As in other illusions, a pilot in a prolonged, coordinated, and constant-rate turn will eventually experience the illusion of not turning. [Figure 2]

- An observed loss of altitude during a coordinated constant-rate turn that has ceased stimulating the motion sensing system can create the illusion of being in a descent with level wings.

- During the recovery to level flight, the pilot will experience the sensation of turning in the opposite direction (leans).

- The pilot may return the aircraft to its original turn and, in doing so, continue to lose altitude.

- Instruments will likely indicate a descent at this point, causing the pilot to try to correct for the illusion of a level descent.

- The pilot pulls back on the yoke, tightening the spiral, increasing the rate of descent.

-

Somatogravic Illusion:

- A rapid acceleration, like that experienced during takeoff, stimulates the otolith organs in the same way as tilting the head backward.

- This action creates the illusion of having a nose-up attitude, especially in situations where there are no explicit visual references.

- The disoriented pilot may push the aircraft into a nose-low or dive attitude.

- A rapid deceleration, achieved by a quick reduction of the throttle(s), can have the opposite effect, with the disoriented pilot pulling the aircraft into a nose-up or stall attitude.

- A rapid acceleration, like that experienced during takeoff, stimulates the otolith organs in the same way as tilting the head backward.

-

Inversion Illusion:

- An abrupt change from a climb to straight and level will make the pilot feel as though they are tumbling backward.

- The disoriented pilot will push the nose forward (low) and possibly intensify the illusion.

- It is as though you're in a recliner, and you feel as though you're looking up, but gravity is actually pulling you into the chair. In reality, you're descending, and the aircraft's acceleration downward is pushing you into the seat.

-

Elevator Illusion:

- An abrupt upward vertical acceleration, like when in an updraft, can stimulate the otolith organs to create the illusion of being in a climb.

- The disoriented pilot may push the aircraft into a nose-low attitude.

- An abrupt downward vertical acceleration, typically in a downdraft, has the opposite effect, causing the disoriented pilot to pull the aircraft into a nose-up attitude.

- An abrupt upward vertical acceleration, like when in an updraft, can stimulate the otolith organs to create the illusion of being in a climb.

-

Visual/Night Illusions:

- Of the senses, vision is the most important for safe flight.

- However, various terrain features and atmospheric conditions can create optical illusions.

- These illusions are primarily associated with landing.

- Since pilots must transition from reliance on instruments to visual cues outside the flight deck for landing at the end of an instrument approach, they must be aware of the potential problems associated with these illusions and take appropriate corrective action.

-

False Horizon:

- Low-light nights tend to eliminate reference to a visual horizon.

- Sloping cloud formations, an obscured horizon, a dark scene spread with ground lights and stars, and specific geometric patterns of ground light can create the illusion of not being aligned with the horizon.

- Geometric patterns of ground light can create illusions that the light is not aligned correctly with the actual horizon.

- The disoriented pilot will align with an incorrect horizon and, hence, a dangerous attitude.

- As a result, pilots need to rely less on outside references at night and more on flight and navigation instruments.

-

Autokinesis:

- Caused by staring at a single point of light against a dark background for more than a few seconds.

- After a few moments, the light appears to move on its own.

- The disoriented pilot will lose control of the aircraft as they attempt to align it with the light.

- To prevent this illusion, focus your eyes on objects at varying distances and avoid fixating on a single target.

- Be sure to maintain a typical scan pattern.

-

Vertigo:

- A feeling of dizziness and disorientation caused by doubt in visual interpretation.

- Distractions and problems can result from a flickering light in the cockpit, anti-collision light, strobe lights, or other aircraft lights, and can cause flicker vertigo.

- Often experienced due to a lack of a well-defined horizon.

- Also experienced leaving a well-lit area (a runway) into darkness.

- Possible physical reactions include nausea, dizziness, grogginess, unconsciousness, headaches, or confusion.

-

Black-hole Approach:

- When landing at night from over water or non-lighted terrain, the runway lights are the only source of light.

- Without peripheral visual cues to help, pilots will have trouble orienting themselves relative to Earth (horizon).

- The runway can appear to be out of position (down-sloping or up-sloping) and, in the worst case, result in landing short of the runway.

- Utilize visual glide-slope indicators, if available.

- If navigation aids (NAVAIDs) are unavailable, pilots should pay careful attention to using the flight instruments to maintain orientation and adhere to a standard approach profile.

- Difficulty judging distance and distinguishing approach from runway lights further complicates night landings:

- Bright runway and approach lighting systems, particularly in areas with limited lighting, may create the illusion of a shorter distance to the runway, leading to a higher-than-normal approach angle.

- When flying over terrain with only a few lights, the runway will appear to recede or appear farther away, leading to a lower-than-normal approach.

- If the runway is near a city on higher terrain in the distance, the tendency will be to fly a lower-than-normal approach.

- A good review of the airfield layout and boundaries before initiating any approach will help the pilot maintain a safe approach angle.

- For example, when a double row of approach lights meets the boundary lights of the runway, there can be confusion about where the approach lights end and the runway lights begin.

- Under certain conditions, approach lights can make the aircraft seem higher in a turn to final than when its wings are level.

- The pilot should execute a go-around if they are unsure of their position or altitude at any time.

- The black-hole illusion is not just a problem for approaches, but also for departures.

- See also: AOPA Air Safety Institute - Safety Quiz: IFR Into a Black Hole.

-

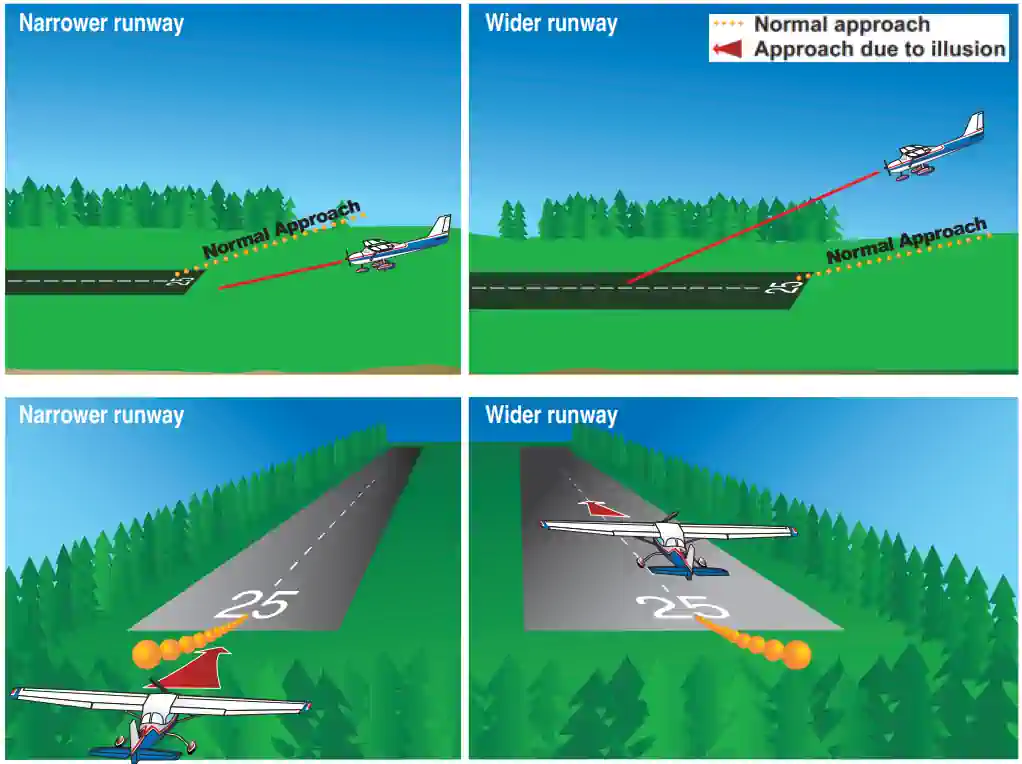

Landing Illusions:

- Various surface features and atmospheric conditions encountered in landing can create illusions of incorrect height above and distance from the runway threshold.

- Anticipating landing error illusions can prevent them during approaches, aerial visual inspections of unfamiliar airports (before landing), the use of glide slope or VASI systems when available, and maintaining optimum proficiency in landing procedures.

-

Runway Width:

[Figure 3]- A narrower-than-usual runway can create an illusion in which the aircraft appears to be at a higher altitude than it actually is, especially when the runway's length-to-width ratio is comparable.

- The pilot who does not recognize this illusion will fly a lower approach, with the risk of striking objects along the approach path or landing short of the intended position.

- A wider-than-usual runway can have the opposite effect, with the risk of leveling out high and landing hard or overshooting the runway.

- A narrower-than-usual runway can create an illusion in which the aircraft appears to be at a higher altitude than it actually is, especially when the runway's length-to-width ratio is comparable.

-

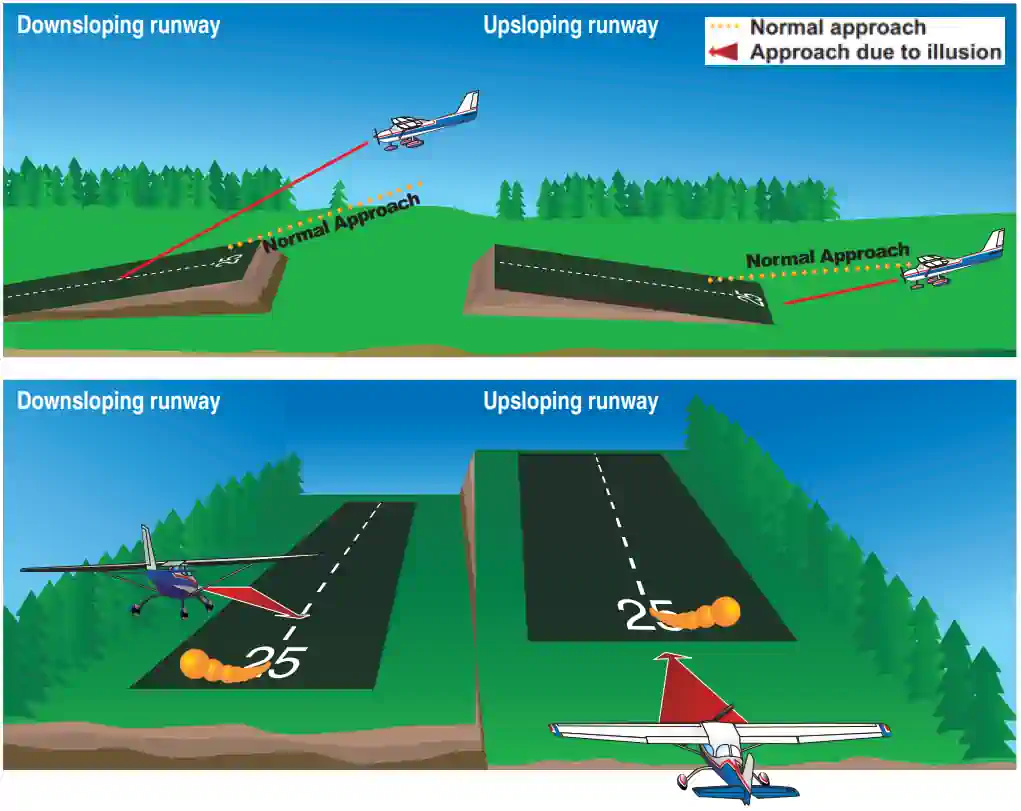

Runway Slope:

[Figure 4]- An up-sloping runway, up-sloping terrain, or both can create an illusion that the aircraft is at a higher altitude than it is.

- The pilot who does not recognize this illusion will fly a lower approach.

- Down-sloping runways and down-sloping approach terrain can cause pilots to fly higher approaches.

- Flying a higher approach can impact landing performance, reducing the available runway and increasing approach speeds as pilots attempt to lose excess altitude.

- An up-sloping runway, up-sloping terrain, or both can create an illusion that the aircraft is at a higher altitude than it is.

-

Featureless Terrain:

- A lack of horizon or surface reference is common during overwater flights, at night, or in low visibility conditions.

- An absence of surrounding ground features, such as an overwater approach, a darkened area, or terrain made featureless by snow, can create an illusion that the aircraft is at a higher altitude than it is.

- This illusion is sometimes referred to as the "black hole approach" (explained above), causing pilots to fly a lower approach than is desired.

-

Ground Lighting:

- Light along a straight path, such as a road, can be mistaken for a runway.

- Bright runway and approach lighting systems, especially where few lights illuminate the surrounding terrain, may create the illusion of less distance to the runway, causing pilots to fly a higher approach.

- Conversely, the pilot overflying terrain, which has few lights to provide height cues, may make a lower-than-normal approach.

-

Aircraft Lighting:

- When the landing light illuminates the runway, just as with ground lighting illusions, it makes the lighted area appear higher than the non-lighted area.

- As a result, pilots may fly a higher-than-normal approach.

-

Atmospheric Illusions:

- Illusions concerning the weather and the appearance it creates regarding the terrain.

- Surface references or the natural horizon may at times become obscured by smoke, fog, smog, haze, dust, ice particles, or other phenomena.

- However, visibility may be above the minimums required for Visual Flight Rules (VFR).

- Obscuration is more likely at airports located adjacent to large bodies of water or sparsely populated areas, where few, if any, surface references are available.

- Other contributors to disorientation are reflections from outside lights, sunlight shining through clouds, and light beams from the airplane's anti-collision rotating beacon.

-

Water Refraction:

- Rain on the windscreen can create an illusion of being at a higher altitude because the horizon appears lower than it is.

- Pilots experiencing a water refraction-induced illusion may fly a lower approach than is desired.

- Rain on the windscreen can create an illusion of being at a higher altitude because the horizon appears lower than it is.

-

Haze:

- Haze can create an illusion of being farther from the runway.

- As a result, the pilot will tend to be low on the approach.

- Clear air (clear, bright conditions of a high-altitude airport) can give the pilot the illusion of being closer to the runway.

- As a result, the pilot will tend to fly high on approach, which may result in an overshoot or a go-around.

- The diffusion of light due to water particles on the windshield can adversely affect depth perception.

- The lights and terrain features commonly used to gauge height during landing become less effective for the pilot.

- Haze can create an illusion of being farther from the runway.

-

Fog:

- Penetration of fog can create an illusion of pitching up.

- Pilots experiencing a fog-induced illusion may fly an abruptly steepened approach.

- It is not a matter of if, but when a pilot experiences some form of spatial disorientation, requiring the knowledge to cope with and extricate themselves from the situation.

Coping with Spatial Disorientation

- The sensations that lead to illusions during instrument flight conditions are everyday perceptions that pilots experience.

- Pilots cannot wholly prevent undesirable sensations, but through training and awareness, they can learn to ignore or suppress them by developing absolute reliance on the flight instruments.

- As pilots gain proficiency in instrument flying, they become less susceptible to these illusions and their effects.

- To prevent illusions and their potentially disastrous consequences, pilots must:

- Understand the causes of these illusions and remain always alert for them. Take the opportunity to understand and then experience spatial disorientation illusions in a device such as a Barany chair, a Vertigon, or a Virtual Reality Spatial Disorientation Demonstrator.

- Always obtain and understand preflight weather briefings.

- Before flying in marginal visibility (less than 3 miles) or where a visible horizon is not evident, such as flight over open water during the night, obtain training and maintain proficiency in airplane control by reference to instruments.

- Only continue flight into adverse weather conditions or dusk or darkness if proficient in using flight instruments. If you intend to fly at night, maintain your night-flight currency and proficiency to ensure safe operations. Include cross-country and local operations at various airfields.

- Ensure that when using outside visual references, they are reliable, fixed points on the Earth's surface.

- Avoid sudden head movement, particularly during takeoffs, turns, and approaches to landing.

- Be physically tuned for flight into reduced visibility by following the "IMSAFE" checklist. That is, ensure proper rest and adequate diet, and allow for night adaptation if flying at night. Remember that illness, medication, alcohol, fatigue, sleep loss, and mild hypoxia are likely to increase susceptibility to spatial disorientation.

- Most importantly, become proficient in using flight instruments and rely upon them. Trust the instruments and disregard your sensory perceptions.

- Coping is a reactive tool, but pilots should work to prevent spatial disorientation.

Spatial Disorientation Prevention

- Since it is not a matter of if, but when a pilot experiences spatial disorientation, there are a few things pilots can do to prepare.

- Fly often.

- Do not fly in instrument meteorological conditions if not rated for them.

- Practice partial panel instrument training (with a safety pilot) on a regular basis.

- Various complex motions and forces, as well as specific visual scenes encountered in flight, can create illusions of motion and position.

- Spatial disorientation resulting from these illusions can be prevented only by visual reference to reliable, fixed points on the ground or by using flight instruments.

- Be aware of the possibility of visual illusions during approaches to unfamiliar airports, especially at night or in adverse weather conditions.

- Consult airport diagrams and the Chart Supplement U.S. for information on runway slope, terrain, and lighting.

- Make frequent reference to the altimeter, especially during all approaches, day and night.

- Conduct an aerial visual inspection of unfamiliar airports before landing.

- Use the Visual Approach Slope Indicator (VASI) or the Precision Approach Path Indicator (PAPI) systems for a visual reference or an electronic glide slope whenever they are available.

- Utilize the Visual Descent Point (VDP) found on many non-precision instrument approach procedure charts.

- Recognize that the chances of being involved in an approach accident increase when some emergency or other activity distracts from usual procedures.

- The following fundamental steps assist in preventing spatial disorientation:

- Before flying with less than 3 miles of visibility, obtain training and maintain proficiency in airplane control by reference to instruments.

- When flying at night or in reduced visibility, use the flight instruments to maintain your position and altitude.

- Maintain your night currency if you intend to fly at night. Include cross-country and local operations at different airports.

- Study and become familiar with the unique geographical conditions.

- Check weather forecasts before departure, enroute, and at your destination. Be alert for weather deterioration.

- Plan your transition to instrument flying before you enter IMC. Start your instrument scan while you are still in visual conditions.

- Do not attempt visual flight when there is a possibility of getting trapped in deteriorating weather.

- Rely on instrument indications unless the natural horizon or surface reference is visible.

- Consider practicing maneuvers that illicit illusions with your flight instructor to maintain proficiency.

- Set personal minimums for VFR and IFR flight designed to minimize your exposure to conditions that increase your risks.

Spatial Disorientation Demonstration

- A spatial disorientation demonstration enhances flight training by exposing student pilots to various sensations they could encounter in flight, as well as the attitudes that could trigger those sensations.

-

Spatial Disorientation Demonstration Purpose:

- There are several controlled aircraft maneuvers a pilot can perform to experiment with spatial disorientation.

- While each maneuver will generally create a specific illusion, any false sensation is a practical demonstration of disorientation.

- Thus, even if there is no sensation during any of these maneuvers, the absence of sensation is still a practical demonstration in that it shows the inability to detect bank or roll.

- There are several objectives in demonstrating these various maneuvers.

- A pilot should not attempt any of these maneuvers at low altitudes or in the absence of an instructor pilot or an appropriate safety pilot.

- In the descriptions of these maneuvers, the instructor pilot is typically doing the flying; however, having the pilot perform the flying can also be an efficient demonstration.

- The pilot should close their eyes and tilt their head to one side.

- The instructor pilot instructs the pilot on the control inputs to perform.

- The pilot then attempts to establish the correct attitude or control input with eyes closed and head tilted.

- While it is clear that the pilot has no idea of the actual attitude, they will react to what their senses are telling them.

- After a short time, the pilot will become disoriented, and the instructor pilot then tells the pilot to look up and recover.

- The benefit of this exercise is that the pilot experiences the disorientation while flying the aircraft.

- They teach pilots to understand the susceptibility of the human system to spatial disorientation.

- They demonstrate that judgments of aircraft attitude based on bodily sensations are frequently false.

- They help reduce the occurrence and severity of disorientation by providing a better understanding of the relationship between aircraft motion, head movements, and resulting disorientation.

- They help instill a greater confidence in relying on flight instruments for assessing aircraft attitude.

-

Spatial Disorientation Demonstration Procedure:

-

Climbing While Accelerating:

- With the pilot's eyes closed, the instructor pilot maintains approach airspeed in a straight-and-level attitude for several seconds, and then accelerates while maintaining the same attitude.

- The usual illusion during this maneuver, without visual references, will be that the aircraft is climbing.

-

Climbing While Turning:

- With the pilot's eyes still closed and the aircraft in a straight-and-level attitude, the instructor pilot now executes, with a relatively slow entry, a well-coordinated turn of about 1.5 positive G (approximately 50° bank) for 90°.

- Without outside visual references in a turn and under the effect of the slight positive G, the usual illusion produced is that of a climb.

- Upon sensing the climb, the pilot should immediately open the eyes and see that a slowly established, coordinated turn produces the same feeling as a climb.

-

Diving While Turning:

- Repeating the previous procedure, while keeping your eyes closed until about halfway through recovery from the turn, can create this sensation.

- With the eyes closed, the usual illusion will be that the aircraft is diving.

-

Tilting to the Right or Left:

- While in a straight-and-level attitude, with the pilot's eyes closed, the instructor pilot executes a moderate or slight skid to the left with wings level.

- This maneuver creates the illusion of the body tilting to the right.

-

Reversal of Motion:

- Any of the three planes of motion demonstrates the reversal of motion illusion.

- While the aircraft is straight and level, with the pilot's eyes closed, the instructor pilot smoothly and positively rolls the aircraft to approximately a 45° bank angle, maintaining its heading and pitch attitude.

- The reversal of motion illusion creates a strong sense of rotation in the opposite direction.

- After creating this illusion, the pilot should open their eyes and observe that the aircraft is in a banked attitude.

- Any of the three planes of motion demonstrates the reversal of motion illusion.

-

Diving or Rolling Beyond the Vertical Plane:

- This maneuver may produce extreme disorientation.

- While in straight-and-level flight, the pilot should sit normally, either with eyes closed or gaze lowered to the floor.

- The instructor pilot starts a positive, coordinated roll toward a 30° or 40° angle of bank.

- As this is in progress, the pilot tilts their head forward, looks to the right or left, then immediately returns their head to an upright position.

- The instructor pilot should time the maneuver so that the roll stops as the pilot returns their head to an upright position.

- This maneuver typically produces intense disorientation, and the pilot experiences the sensation of falling downward in the direction of the roll.

-

Spatial Disorientation & Illusions in Flight Case Studies

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: WPR11FA256:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: the non-instrument-rated pilot's decision to conduct a visual flight rules flight over mountainous terrain into a region covered by clouds, which likely resulted in spatial disorientation and subsequent loss of airplane control.

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: CEN13FA135:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot's inadvertent controlled descent into terrain due to spatial disorientation. Contributing to the accident was the lack of a visual reference due to the night conditions.

Spatial Disorientation & Illusions in Flight

Spatial Disorientation & Illusions in Flight Conclusion

- Between 5 to 10% of all general aviation accidents are attributed to spatial disorientation, and 90% of those are fatal.

- NTSB data suggest that spatial D is a more common occurrence at night or in weather conditions with limited visibility.

- Illusions rank among the most common factors cited as contributing to fatal aircraft accidents.

- The degree of disorientation may vary considerably with individual pilots, as do the conditions that induce the problem.

- Various complex motions and forces, as well as specific visual scenes encountered in flight, can create illusions of motion and position.

- Spatial disorientation resulting from these illusions can be prevented only by visual reference to reliable, fixed points on the ground or by using flight instruments.

- Remember, once you enter instrument conditions, completely commit to instrument flying.

- Attempting quick transitions to visual flight because you spotted a hole in the clouds or caught a glimpse of the ground below may cause spatial disorientation that could have been avoided by maintaining a proper instrument scan.

- The acronym "ICEFLAGS" serves as a tool to remember the different types of vestibular and visual/nighttime illusions.

- Inversion, Coriolis, Elevator, False horizon, Leans, Autokinesis, Graveyard Spiral, Somatogravic.

- Review your illusions in flight knowledge by taking the Air Safety Institute's "Into a Black Hole" quiz.

- Consider completing the AOPA's Spatial Orientation Spotlight to learn more about spatial disorientation.

- Consider actual versus realized performance when doing any performance calculations.

- Consider practicing maneuvers on a flight simulator to familiarize yourself with them or knock off the rust.

- Still looking for something? Continue searching:

Spatial Disorientation & Illusions in Flight

Spatial Disorientation & Illusions in Flight References

- Federal Aviation Administration - Pilot/Controller Glossary.

- Federal Aviation Administration - Aerospace Physiology Training Class.

- Instrument Flying Handbook (1-5) Illusions Leading to Spatial Disorientation.

- Instrument Flying Handbook (1-7) Demonstration of Spatial Disorientation.

- Airplane Flying Handbook (10-2) Night Illusions.

- Advisory Circular 61-21A (Chapter 1) Disorientation (Vertigo).

- Aeronautical Information Manual (8-1-5) Illusions in Flight.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (8-1-6) Vision in Flight.

- AOPA - Safety Quiz - Spatial Disorientation.

- AOPA - Spatial Disorientation: Confusion that Kills.

- BoldMethod - What Is A Graveyard Spiral, And How Do You Avoid It?.

- FAA Medium - It’s a Confusing World Up There.

- Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (16-17) Vision in Flight.

- Quizlet - Types of Illusions - ICEFLAGS.