Aeronautical Decision-Making (ADM)

Aeronautical Decision-Making is the systematic approach to consistently determine the best decision in response to a given set of circumstances.

Introduction to Aeronautical Decision-Making

- Aeronautical Decision-Making is the systematic approach to consistently determine the best decision in response to a given set of circumstances.

- Safe flying requires the effective integration of three separate sets of skills:

- Most noticeable are the basic stick-and-rudder skills needed to control the airplane.

- Next are skills related to the proficient operation of aircraft systems.

- Last but not least are Aeronautical Decision-Making (ADM) skills.

- ADM is an ever-evolving systematic approach to the mental process (risk and stress management) used by pilots to consistently determine the best course of action in response to a given set of circumstances.

- An understanding of the decision-making process provides a pilot with a foundation for developing ADM skills.

- While these models guide pilots to help prevent facing the consequences of improper decision-making, decision-making in a dynamic environment provides unique challenges for each flight.

- To maintain readiness for dynamic situations, pilots must continuously practice maintaining situational awareness of their surroundings.

- Two defining elements of ADM are hazard and risk.

- While the FAA strives to eliminate errors through technology, training, systems, and improved flight safety programs, one fact remains: humans make errors.

- There is an element of risk in every flight, and therefore, pilots must apply the principles of risk management throughout the ADM process.

- Think you've got a solid understanding of aeronautical decision making? Don't miss the aeromedical decision-making quiz below, and the topic summary.

Aeronautical Decision-Making History

- For over 25 years, the importance of good pilot judgment, also known as aeronautical decision-making (ADM), has been recognized as critical to the safe operation of aircraft and accident avoidance.

- The airline industry, motivated by the need to reduce accidents caused by human factors, developed the first of several training programs to improve ADM.

- Crew resource management (CRM) training for flight crews focuses on effectively utilizing all available resources, including human resources, hardware, and information, to support ADM and facilitate crew cooperation, thereby improving decision-making.

- The goal of all flight crews is to maintain good ADM, and the use of CRM is one way to facilitate sound decision-making.

- Research prompted the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to develop training aimed at enhancing pilots' decision-making skills, ultimately leading to current FAA regulations that require decision-making education as part of the pilot training curriculum.

- ADM research, development, and testing culminated in 1987 with the publication of six manuals tailored to the decision-making needs of variously rated pilots.

- These manuals provided multifaceted materials designed to reduce the number of decision-related accidents.

- Independent studies validated the effectiveness of these materials by training student pilots with them alongside the standard flying curriculum.

- When tested, the pilots who had received ADM training made fewer in-flight errors than those who had not received ADM training.

- The differences were statistically significant, ranging from 10% to 50% fewer judgment errors.

- In the operational environment, an operator flying about 400,000 hours annually demonstrated a 54% reduction in accident rate after using these materials for recurrency training.

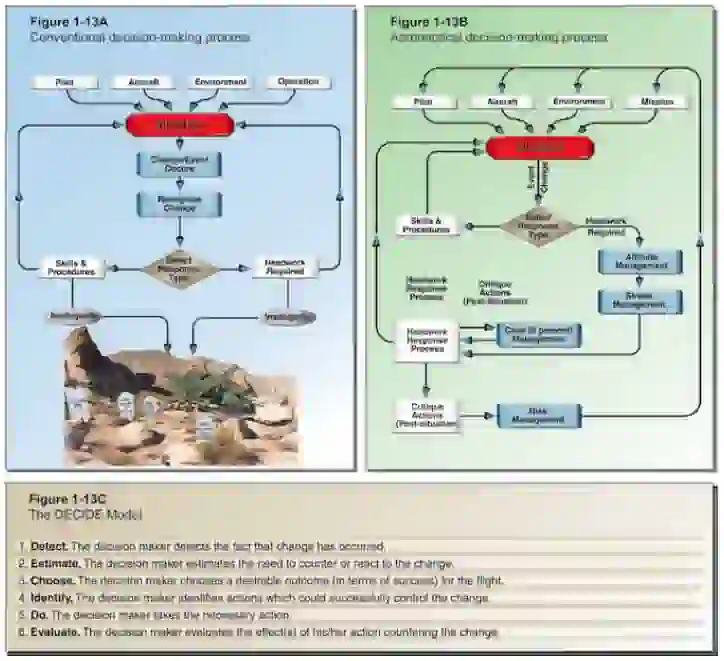

- Contrary to popular opinion, instructors can teach good judgment as a skill. Tradition held that good judgment was a natural by-product of experience. Building upon the foundation of conventional decision-making, ADM enhances the process to decrease the probability of human error and increase the likelihood of a safe flight. ADM provides a structured and systematic approach to analyzing changes that occur during a flight and how these changes might affect the safe outcome of the flight.

- While the ADM process will not eliminate errors, it will help the pilot recognize mistakes, and in turn, enable the pilot to manage the error to minimize its effects by:

- Identifying personal attitudes hazardous to safe flight.

- Learning behavior modification techniques.

- Learning how to recognize and cope with stress.

- Developing risk assessment.

- Using all resources.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of one's ADM skills.

- Historically, the term "pilot error," which refers to an action taken by the pilot that was the cause or a contributing factor to the accident, has been used to describe the causes of these accidents.

- This definition also includes the pilot's failure to make a decision or take action.

- From a broader perspective, the phrase "human factors related" more aptly describes these accidents, as it is usually not a single decision that leads to an accident, but rather a chain of events triggered by several factors.

- The poor judgment chain, sometimes referred to as the "error chain," is a term used to describe the contributing factors in a human-related accident.

- Breaking one link in the chain is typically all that is necessary to change the outcome of the sequence of events.

The Decision-Making Process

- An understanding of the decision-making process provides the pilot with a foundation for developing ADM skills.

- While some situations, such as engine failure, require an immediate pilot response using established procedures, there is usually time during a flight to analyze any changes that occur, gather information, and assess risks before reaching a decision.

- Immediate action procedures are a form of "automatic decision-making" based upon training, experience, and recognition.

- Risk management and risk intervention are decision-making processes designed to systematically identify hazards, assess the degree of risk, and determine the best course of action.

- These processes involve identifying hazards, assessing risks, analyzing controls, making control decisions, implementing controls, and monitoring the results to ensure effectiveness.

- The steps leading to this decision constitute a decision-making process.

-

The Plan, Plane, Pilot, Passengers, and Programming (5P) Model:

- "The plan, the plane, the pilot, the passengers, and the programming" make up the 5P model.

- Each of these areas presents a set of challenges and opportunities that every pilot encounters, which can significantly impact the pilot's ability to make informed and timely decisions.

- The 5 Ps recognize that five variables shape a pilot’s environment, drive critical decisions, and, when combined, can lead to critical outcomes.

- The 5P concept relies on the pilot to adopt a "scheduled" review of the critical variables at points in the flight where decisions are most likely effective. For instance, the easiest point to cancel a flight due to inclement weather is before the pilot and passengers board the aircraft. The first decision point is preflight in the flight planning room, where all the necessary information is readily available to make a sound decision. Additionally, communication and Fixed Base Operator (FBO) services are readily available to facilitate alternate travel plans.

-

Go/No-Go Decision:

- The second most critical point in the flight to make a safety decision is just before takeoff.

- Few pilots have ever had to make an "emergency takeoff."

- The 5P check exists to help the pilot apply the 5P correctly before takeoff, making a reasoned go/no-go decision based on all available information.

- That decision will usually be to "go," with certain restrictions and changes, but may also be a "no-go."

- The key idea is that these two points in the flight process are critical go/no-go points on each flight.

- Consider approaching the problem differently, whereby it's a no-go unless certain conditions materialize.

- The second most critical point in the flight to make a safety decision is just before takeoff.

- The third place to review the 5Ps is at the midpoint of the flight. Pilots may often wait until the Automated Terminal Information Service (ATIS) is in range to check the weather. Yet, many good options have already passed behind the aircraft and pilot at this point in the flight. Additionally, fatigue and low-altitude hypoxia can significantly deplete the pilot's energy by the end of a long and tiring flight day. Pilots may transition from a decision-making mode to an acceptance mode. If the flight is longer than 2 hours, pilots should conduct the 5P check at least hourly.

- The last two decision points are just before descent into the terminal area and before the final approach fix, or if VFR, just before entering the traffic pattern as preparations for landing commence. Most pilots execute approaches with the expectation that they will land out of the approach every time. A healthier approach requires the pilot to assume that changing conditions (the 5 Ps again) will cause them to divert or execute a missed approach on every approach. Pilots then remain alert to all manner of conditions that may increase risk and threaten the safe conduct of the flight. Diverting from cruise altitude saves fuel, allows unhurried use of the autopilot, and is less reactive. Diverting from the final approach fix, while more difficult, still allows the pilot to plan and coordinate better, rather than executing a futile missed approach. Let's look at a detailed discussion of each of the Five Ps.

-

The Plan:

- Flight planning results in not just a flight plan, but also the familiarization with all events that surround the flight.

- The flight plan encompasses the fundamental elements of cross-country planning, including weather, route, fuel, publications, currency, and other pertinent details.

- However, no matter how perfect the plan, external factors such as weather and aircraft status are subject to change at any time.

- For any number of factors that can impact the flight, the "Plan" should be reviewed and updated throughout the flight.

- Several resources, such as datalink weather, FSS, and/or Flight Watch, Pilot Reports, and ATC, can help augment the flight plan.

-

The Plane:

- The "plane" typically presents a range of mechanical and cosmetic issues that every aircraft pilot, owner, or operator can readily identify.

- With the advent of advanced avionics, the "plane" has expanded to include database currency, automation status, and emergency backup systems that were previously unknown.

- Many have written about single-pilot IFR flight, both with and without an autopilot.

- While this is a personal decision, it is just that-a decision.

- Low IFR in a non-autopilot-equipped aircraft may depend on several of the other Ps.

- Pilot proficiency, currency, and fatigue are among them.

-

The Pilot:

- Flying, especially when business transportation is involved, can expose pilots to risks such as high altitudes, long trips requiring significant endurance, and challenging weather conditions.

- Advanced avionics, when installed, can expose a pilot to high stress because of the additional capabilities they offer.

- When dealing with pilot risk, it is always best to consult the "IMSAFE" checklist. The combination of late nights, pilot fatigue, and the effects of sustained flight above 5,000 feet may cause pilots to become less discerning, less critical of information, less decisive, and more compliant and accepting.

- Just as the most critical portion of the flight approaches (for instance, a night instrument approach in poor weather conditions after a 4-hour flight), the pilot's guard is down the most.

- The 5 P process helps a pilot recognize the physiological challenges that they may face towards the end of the flight before takeoff.

- It allows them to update personal conditions as the flight progresses.

- With risks identified, the pilot is in a better position to develop alternative plans that mitigate the effects of these factors and provide a safer solution.

-

The Passengers:

- One of the key differences between CRM and SRM is the way passengers interact with the pilot.

- The pilot of a single-engine aircraft maintains a more personal relationship with the passengers, as they are within arm's reach throughout the flight.

- Passengers can also be pilots. Designated a pilot in command (PIC) for unplanned circumstances to avoid conflicting decision-making styles of several self-confident pilots.

- Pilots also need to understand that non-pilots may not understand the level of risk involved in flight. While a pilot may feel comfortable with the risk present in a night IFR flight, the passengers may not. A pilot employing SRM should ensure that passengers are involved in the decision-making process and given tasks and duties to keep them busy and engaged. If the passengers are not comfortable with a factual description of the risks present, then a good decision has generally been made. This discussion also allows the pilot to move past what they think the passengers want to do and discover what they actually want to do, removing self-induced pressure from the pilot.

- One of the key differences between CRM and SRM is the way passengers interact with the pilot.

-

The Programming:

- The electronic instrument displays, GPS, and autopilot reduce pilot workload and increase pilot situational awareness.

- These devices, however, tend to capture the pilot's attention and hold it for long periods.

- To avoid this phenomenon, the pilot must program for approaches, route changes, and gathering airport information, as well as times when it should not.

- Pilot familiarity with the equipment, the route, the local ATC environment, and personal capabilities concerning the automation should drive when, where, and how the automation is programmed and used.

- "The plan, the plane, the pilot, the passengers, and the programming" make up the 5P model.

-

Perceive, Process, Perform (3P) Model:

- The Perceive, Process, Perform (3P) model for ADM provides a straightforward, practical, and systematic approach applicable throughout all phases of flight. [Figure 1]

- To use it, the pilot will:

- Perceive the given set of circumstances for a flight.

- Evaluate their impact on flight safety.

- Perform by implementing the best course of action.

- Use the Perceive, Process, Perform, and Evaluate method as a continuous model for every aeronautical decision you make. Although human beings will inevitably make mistakes, anything that you can do to recognize and minimize potential threats to your safety will make you a better pilot.

- Depending upon the nature of the activity and the time available, risk management processing can occur in any of three timeframes. Most flight training activities happen in the "time-critical" timeframe for risk management. The 3P model combines six risk management steps for practical risk management: Perceive, Process, and Perform, utilizing the PAVE, CARE, and TEAM checklists. Pilots can help identify hazards by using the PAVE checklist, which includes Pilot, Aircraft, enVironment, and External pressures. They can process hazards using the CARE checklist, which stands for Consequences, Alternatives, Reality, and External factors. Finally, pilots can perform risk management by using the TEAM choice list, which includes the options of Transfer, Eliminate, Accept, or Mitigate.

-

The PAVE Checklist:

- See: PAVE Checklist.

-

The IM-SAFE Checklist:

- See: IM-SAFE Checklist.

-

CARE Checklist: Review Hazards and Evaluate Risks:

- In the second step, the goal is to process this information to determine whether the identified hazards constitute a risk, defined as the future impact of a hazard that is not controlled or eliminated. Risk measures in terms of exposure (number of people or resources affected), severity (extent of possible loss), and probability (the likelihood that a hazard will cause a loss). The goal is to evaluate their impact on the safety of your flight and consider, "Why must I CARE about these circumstances?"

- For each hazard that you perceived in step one, use the CARE checklist of Consequences, Alternatives, Reality, and External factors. For example, let's evaluate a night flight to attend a business meeting:

- Consequences: departing after a full workday creates fatigue and pressure.

- Alternatives: delay until morning, reschedule the meeting, or drive.

- Reality: dangers and distractions of fatigue could lead to an accident.

- External pressures: a business meeting at the destination might influence me.

- A good rule of thumb for the processing phase: if you find yourself saying that it will "probably" be okay, it is time for a solid reality check. If you are worried about missing a meeting, be realistic about how that pressure will affect not just your initial go/no-go decision but also your in-flight decisions to continue the flight or divert.

-

TEAM Checklist: Choose and Implement Risk Controls:

- Perform risk management by using the TEAM checklist of Transfer, Eliminate, Accept, Mitigate to deal with each factor:

- Transfer-Should this risk decision be transferred to someone else (e.g., do you need to consult the chief flight instructor?)

- Eliminate: Is there a way to eliminate the hazard?

- Accept: Do the benefits of accepting risk outweigh the costs?

- Mitigate: What can you do to mitigate the risk?

- The goal is to eliminate hazards or mitigate risk and then continuously evaluate the outcome of this action. With the example of low ceilings at the destination, the pilot can perform good ADM by selecting a suitable alternate, knowing where to find good weather, and carrying sufficient fuel to reach it. This course of action would mitigate the risk. The pilot also has the option to eliminate it by waiting for better weather.

- Once the pilot has completed the 3P decision process and selected a course of action, the process begins anew. Now the set of circumstances brought about by the course of action requires analysis. The decision-making process is a continuous loop of perceiving, processing, and performing. With practice and consistent use, running through the 3P cycle can become a habit that is as smooth, continuous, and automatic as a well-honed instrument scan.

- Your mental willingness to follow through on safe decisions, especially those that require delay or diversion, is critical. You can bulk up your mental muscles by:

- Use of a personal minimums checklist to make some decisions in advance of the flight. To develop a good personal minimums checklist, you need to assess your abilities and capabilities in a non-flying environment, when there is no pressure to make a specific trip. Once developed, a personal minimums checklist will provide a clear and concise reference point for building your go/no-go or continue/discontinue decisions.

- Instead of establishing personal minimums, some pilots also prefer to use a preflight risk assessment checklist to aid in the ADM and risk management processes. This type of form assigns numbers to specific risks and situations, making it easier to identify when a particular flight involves a higher level of risk.

- Develop a list of good alternatives during your processing phase. In marginal weather, for instance, you might mitigate the risk by identifying a reasonable alternative airport for every 25–30 nautical mile segment of your route.

- Preflight your passengers by preparing them for the possibility of delay and diversion, and involve them in your evaluation process.

- Another essential tool, often overlooked by many pilots, is a thorough post-flight analysis. When you have safely secured the airplane, take the time to review and analyze the flight as objectively as you can. Mistakes and judgment errors are inevitable; the most important thing is for you to recognize, analyze, and learn from them before your next flight.

- The goal is to take action to eliminate hazards or mitigate risk, and then continuously evaluate the outcome of this action.

- Perform risk management by using the TEAM checklist of Transfer, Eliminate, Accept, Mitigate to deal with each factor:

-

The DECIDE Model:

- DECIDE means to Detect, Estimate, Choose a course of action, Identify solutions, Do the necessary actions, and Evaluate the effects of the actions. [Figure 2]

-

Detect (the Problem):

- Detection begins with (correctly) recognizing that a change occurred, or an expected change did not happen.

- A problem is perceived first by the senses, and then it is distinguished through insight and experience.

- These abilities, combined with an objective analysis of all available information, determine the nature and severity of the problem.

- For example, a low oil pressure reading could indicate that the engine is about to fail, requiring an emergency landing, or it could mean that the oil pressure sensor has failed.

- The actions taken in each of these circumstances would be significantly different.

- One requires an immediate decision based upon training, experience, and evaluation of the situation, whereas analysis drives the latter.

- Note that the same indication could result in two different actions depending upon other influences.

-

Estimate (the need to react):

- After identifying the problem, the pilot must assess the need to respond to it and determine the necessary actions to resolve the situation within the available time.

- In many cases, overreaction and fixation exclude a safe outcome. For example, what if the cabin door of your aircraft suddenly opened in flight while the aircraft climbed through 1,500 feet on a clear sunny day? The sudden opening may alarm you, but you can quickly and effectively assess the perceived hazard as minor. Most likely, a pilot would return to the airport to secure the door after landing.

- The pilot flying on a clear day, faced with this minor problem, may rank the open cabin door as low risk. What about the pilot on an IFR climb out in IMC conditions, with intermittent light turbulence in the rain, while receiving an amended clearance from ATC? The open cabin door now becomes a higher risk factor. The problem remains unchanged, but the perception of risk a pilot assigns to it changes due to the multitude of ongoing tasks and the environment in which they operate. Experience, discipline, awareness, and knowledge influence how a pilot ranks a problem.

-

Choose (a course of action):

- After identifying the problem and estimating its impact, the pilot must determine the desired outcome and choose a course of action.

- Consider the expected outcome of each possible action and the risks assessed before deciding on a response to the situation.

-

Identify (solutions):

- The pilot formulates a plan that will take them to the objective. Sometimes, there may be only one course of action available. If an engine fails at 500 feet or below, the pilot solves the problem by identifying one or more solutions that lead to a successful outcome. It is essential for the pilot not to become fixated on the process to the exclusion of making a decision.

-

Do (the necessary actions):

- Once identifying pathways to resolution, the pilot selects the most suitable one for the situation. The multiengine pilot, given the simulated failed engine, must now safely land the aircraft.

-

Evaluate (the effect of the action):

- Finally, after implementing a solution, evaluate the decision to see if it was correct.

- It is essential to think ahead and consider how the decision could impact other phases of the flight.

- As the flight progresses, the pilot must continually evaluate the outcome of the decision to ensure it is producing the desired result.

- Another structured approach to ADM is the DECIDE model, a six-step process that provides a logical framework for decision-making.

- The model primarily focuses on the intellectual component but can also influence the motivational element of judgment.

- If a pilot consistently applies the DECIDE Model in all decision-making, it becomes natural and leads to better decisions in all types of situations.

- In conventional decision-making, the need for a decision arises when recognizing that something has changed or an expected change has not occurred.

- Recognition of the change, or lack of change, is a vital step in any decision-making process.

- Failing to notice changes in a situation can lead directly to a mishap.

- [Figure 3a] The change indicates that an appropriate response or action is necessary to modify the situation (or, at least, one of the elements that comprise it) and bring about a desired new situation.

- Therefore, situational awareness is crucial to making successful and safe decisions.

- At this point, the pilot needs to evaluate the entire range of possible responses to the detected change and to determine the best course of action.

- [Figure 3b] illustrates how the ADM process expands conventional decision-making, shows the interactions of the ADM steps, and how these steps can produce a safe outcome.

- Starting with the recognition of change, followed by an assessment of alternatives, pilots make a decision and monitor the results.

- Pilots can use ADM to enhance their conventional decision-making process because it:

- Increases their awareness of the importance of attitude in decision-making.

- Teaches the ability to search for and establish the relevance of information.

- Increases their motivation to choose and execute actions that ensure safety in the situational time frame.

Improper Decision-Making Outcomes

- Pilots sometimes get in trouble not because of deficient basic skills or system knowledge but rather because of faulty decision-making skills.

- Although aeronautical decisions may appear to be simple or routine, each decision in aviation often defines the options available for the next decision the pilot must make and the possibilities, good or bad, they provide.

- Therefore, a poor decision made early on in a flight can compromise the safety of the flight at a later time, necessitating more accurate and decisive decisions.

- Conversely, good decision-making early on in an emergency provides greater latitude for options later on.

- FAA Advisory Circular (AC) 60-22 defines ADM as a systematic approach to the mental process of evaluating a given set of circumstances and determining the best course of action.

- ADM thus builds upon the foundation of conventional decision-making, enhancing the process to decrease the probability of pilot error.

- Specifically, ADM provides a structure to help the pilot use all resources to develop comprehensive situational awareness.

Decision-Making in a Dynamic Environment

- A solid approach to decision-making is through analytical models, such as the 5 Ps, 3P, and DECIDE. Good decisions result when pilots gather all available information, review it, analyze the options, rate the options, select a course of action, and evaluate that course of action for correctness.

- In some situations, there is not always time to make decisions based on analytical decision-making skills, also known as automatic or naturalized decision-making.

-

Automatic Decision-Making:

- In an emergency, a pilot might not survive if they rigorously apply analytical models to every decision made, as there is not enough time to consider all the options. Under these circumstances, they should attempt to find the best possible solution to every problem.

- For the past several decades, research into how people make decisions has revealed that experts faced with a task loaded with uncertainty first assess whether the situation strikes them as familiar when pressed for time. Rather than comparing the pros and cons of different approaches, they quickly envision how one or a few possible courses of action in such situations will unfold. Experts take the first workable option they can find. While it may not be the best choice, it often yields excellent results.

- The terms "naturalistic" and "automatic decision-making" have been used to describe this type of decision-making. The ability to make automatic decisions holds for a range of experts, from firefighters to chess players. The expert's ability hinges on recognizing patterns and consistencies that clarify options in complex situations. Experts make a provisional sense of a problem, without actually reaching a decision, by launching experience-based actions that in turn trigger creative revisions.

- Reflexive type of decision-making is rooted in training and experience, which is employed in times of emergencies when there is no time for analytical decision-making. Naturalistic or automatic decision-making improves with training and experience, and a pilot will find themself using a combination of decision-making tools that correlate with individual experience and training.

-

Operational Pitfalls:

- Although more experienced pilots are likely to make more automatic decisions, certain tendencies or operational pitfalls often accompany the development of pilot experience. These are classic behavioral traps that pilots have fallen into. As a rule, more experienced pilots try to complete a flight as planned, please passengers, and meet schedules. The desire to meet these goals can hurt safety and contribute to an unrealistic assessment of piloting skills. All experienced pilots have fallen prey to or felt tempted by these tendencies at some point during their flying careers. Pilots must identify and eliminate these dangerous behaviors, including operational pitfalls.

-

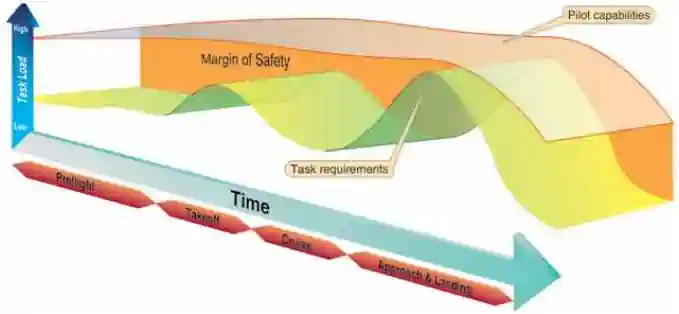

Stress Management:

- Everyone is stressed to some degree almost all of the time. A certain amount of stress is good since it keeps a person alert and prevents complacency. Effects of stress are cumulative and, if the pilot does not appropriately cope, they can eventually add up to an intolerable burden. Performance generally increases with the onset of stress, peaks, and then declines rapidly as stress levels exceed a person's ability to cope with them. Stress impairs the ability to make effective decisions during flight. There are two categories of stress: acute and chronic. These are both explained in Chapter 17, "Aeromedical Factors."

- Factors referred to as stressors can increase a pilot's risk of error in the flight deck. Remember the cabin door that suddenly opened in flight on the Mooney climbing through 1,500 feet on a clear sunny day? It may startle the pilot, but the stress would wane when it became apparent the situation was not a serious hazard. Yet, if the cabin door opens in IMC conditions, the stress level significantly impacts the pilot's ability to cope with simple tasks. The key to stress management is to stop, think, and analyze before jumping to a conclusion. There is usually time to think before drawing unnecessary conclusions.

- There are several techniques to help manage the accumulation of life stresses and prevent stress overload. For example, to help reduce stress levels, set aside time for relaxation each day or maintain a physical fitness program. To prevent stress overload, learn to manage your time more effectively to avoid the pressures of getting behind schedule and missing deadlines.

-

Use of Resources:

- To make informed decisions during flight operations, a pilot must also become aware of the resources found inside and outside the flight deck. Since useful tools and information sources may not always be readily apparent, learning to recognize these resources is an essential part of ADM training. A pilot must also develop the skills to evaluate whether there is sufficient time to use a particular resource and the impact its use will have on flight safety. For example, the assistance of ATC may be beneficial if a pilot becomes lost, but in an emergency, there may be no time available to contact ATC.

-

Internal Resources:

- One of the most underutilized resources may be the person in the right seat, even if the passenger has no flying experience. When appropriate, the PIC can ask passengers to assist with specific tasks, such as watching for traffic or reading checklist items. The following are some other ways a passenger can assist:

- Provide information in an irregular situation, especially if familiar with flying. A strange smell or sound may alert a passenger to a potential problem.

- Confirm after the pilot that the landing gear is down.

- Learn to look at the altimeter for a given altitude in a descent.

- Listen to logic or lack of logic.

- Additionally, a verbal briefing (which can occur whether or not passengers are aboard) can assist the PIC in the decision-making process. For example, assume a pilot provides a briefing to a lone passenger about the forecast landing weather before departure. When listening to the Automatic Terminal Information Service (ATIS), it is evident that the weather has undergone significant changes. The discussion of this forecast change can prompt the pilot to reevaluate their activities and decision-making. Other valuable internal resources include ingenuity, aviation knowledge, and flying skills. Pilots can increase flight deck resources by improving these characteristics.

- When flying alone, another internal resource is verbal communication. Verbal communication reinforces an activity; touching an object while communicating further enhances the probability of completing that activity. For this reason, many solo pilots read the checklist out loud; when they reach critical items, they touch the switch or control. For example, to verify that the landing gear is down, the pilot can refer to the checklist. But if they touch the gear handle during the process, a safe extension of the landing gear is confirmed. Pilots must thoroughly understand all the equipment and systems in their aircraft, such as whether the oil pressure gauge is a direct-reading device or uses a sensor, as this can be the difference between making a wise decision and a poor one that leads to a tragic error.

- Checklists are essential internal resources for the flight deck. They are used to verify that the aircraft's instruments and systems are functioning correctly, and to ensure completion of procedures in the event of a system malfunction or in-flight emergency. Pilots at all levels of experience refer to checklists, and the more advanced the aircraft, the more crucial checklists become. Additionally, the pilot's operating handbook (POH) is required to be carried on board the aircraft and is essential for accurate flight planning and resolving in-flight equipment malfunctions. However, the most valuable resource a pilot has is the ability to manage workload, whether alone or with others.

- One of the most underutilized resources may be the person in the right seat, even if the passenger has no flying experience. When appropriate, the PIC can ask passengers to assist with specific tasks, such as watching for traffic or reading checklist items. The following are some other ways a passenger can assist:

-

External Resources:

- ATC and flight service specialists are the best external resources during a flight. ATC provides pilots with traffic advisories, radar vectors, and emergency assistance to promote the safe and orderly flow of air traffic around airports and along flight routes. Although it is the PIC's responsibility to make the flight as safe as possible, a pilot with a problem can request ATC assistance. For example, if a pilot needs to level off, receive a vector, or decrease speed, ATC assists and becomes an integral part of the crew. The services provided by ATC can not only decrease pilot workload but also help pilots make informed in-flight decisions.

- Flight Service Stations (FSSs) are air traffic facilities that provide pilot briefings, en route communications, VFR search and rescue services, assist lost aircraft and aircraft in emergencies, relay ATC clearances, originate Notices to Airmen (NOTAM), broadcast aviation weather and National Airspace System (NAS) information, receive and process IFR flight plans, and monitor navigational aids (NAVAIDs). Additionally, at select locations, FSSs provide En-Route Flight Advisory Service (Flight Watch), issue airport advisories, and notify Customs and Immigration of transborder flights.

Situational Awareness

- Situational awareness is the accurate perception and understanding of all factors and conditions within the five fundamental risk elements (flight, pilot, aircraft, environment, and type of operation) that comprise any given aviation situation, affecting safety before, during, and after the flight. Monitoring radio communications for traffic, weather discussion, and ATC communication can enhance situational awareness by helping the pilot develop a mental picture of what is happening.

- Maintaining situational awareness requires an understanding of the relative significance and potential future impact of all flight-related factors. When a pilot understands what is going on and has an overview of the total operation, they don't fixate on one perceived significant factor. A pilot needs to know the aircraft's geographical location and what is happening around it. For instance, while flying above Richmond, Virginia, en route to Dulles Airport or Leesburg, the pilot should know why they are receiving vectors and anticipate their spatial location. A pilot who makes turns without understanding why has added to the burden on their management in an emergency. All of the skills involved in ADM maintain situational awareness.

-

Obstacles to Maintaining Situational Awareness:

- Fatigue, stress, and work overload can cause a pilot to fixate on a single perceived essential item, thereby reducing their overall situational awareness during the flight. A contributing factor in many accidents is a distraction that diverts the pilot's attention from monitoring the instruments or scanning outside the aircraft. Many flight deck distractions begin as minor problems, such as a gauge that is not displaying the correct reading. Still, they can result in accidents when the pilot diverts attention to the perceived issue and neglects proper control of the aircraft.

-

Workload Management:

- Effective workload management ensures the accomplishment of essential operations by planning, prioritizing, and sequencing tasks to avoid work overload. As pilots gain experience and learn to recognize future workload requirements, they prepare for high workload periods during periods of low workload. Reviewing the appropriate chart and setting radio frequencies well in advance of when needed helps reduce workload as the flight nears the airport. Additionally, a pilot should listen to the Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS) or Automated Weather Observing System (AWOS), if available, and then monitor the tower frequency or Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) to gauge the expected traffic conditions. Checklists should be performed well in advance, allowing sufficient time to focus on traffic and ATC instructions. These procedures are essential before entering a high-density traffic area, such as Class B airspace.

- Recognizing a work overload situation is also a critical component of managing workload. The first effect of a high workload is that the pilot may be working harder but accomplishing less. As the workload increases, attention capacity decreases, and the pilot may begin to focus on a single item. When a pilot becomes task-saturated, there is a loss of awareness of input from various sources, leading to incomplete decisions, and the possibility of error increases.

- When a work overload situation exists, a pilot needs to stop, think, slow down, and prioritize. It is essential to understand how to decrease the workload. For example, in the case of the cabin door that opened in VFR flight, the impact on workload should be insignificant. If the cabin door opens under IFR under different conditions, its effects on workload change. Therefore, placing a situation in the proper perspective, remaining calm, and reasoning are key elements in reducing stress and increasing the capacity to fly safely. This ability depends upon experience, discipline, and training.

-

Managing Risks:

- The ability to manage risks begins with preparation. Here are some things a pilot can do to manage risks:

- Assess the flight's risk based on experience. Use some form of risk assessment. For example, if the weather is marginal and the pilot has little IMC training, it is probably a good idea to cancel the flight.

- Brief passengers using the SAFETY list:

- S: Seat belts fastened for taxi, takeoff, and landing. Shoulder harness fastened for takeoff and landing. Seat position adjusted and locked in place.

- A: Air vents (location and operation). All environmental controls (discussed). Action in case of any passenger discomfort.

- F: Fire extinguisher (location and operation).

- E: Exit doors (how to secure; how to open). Emergency evacuation plan. Emergency/survival kit (location and contents).

- T: Traffic (scanning, spotting, notifying pilot). Talking ("sterile flight deck" expectations).

- Y: Your questions? (Speak up!).

- In addition to the SAFETY list, discuss with passengers whether or not smoking is permitted, flight route altitudes, time en route, destination, the weather during flight, expected weather at the destination, controls and what they do, and the general capabilities and limitations of the aircraft.

- Use a sterile flight deck (one that is entirely silent with no pilot communication with passengers or by passengers) from the time of departure to the first intermediate altitude and clearance from the local airspace.

- Use a sterile flight deck during arrival from the first radar vector for approach or descent.

- Keep the passengers informed during times when the workload is low.

- Consider using the passenger in the right seat for simple tasks, such as holding the chart to relieve the pilot of a task.

- The ability to manage risks begins with preparation. Here are some things a pilot can do to manage risks:

Risk Management

-

Hazard and Risk:

- Hazard is a real or perceived condition, event, or circumstance that a pilot encounters. [Figure 3]

- When faced with a hazard, the pilot makes an assessment of that hazard based upon various factors.

- Assessing a single or cumulative hazard facing a pilot is a risk.

- The pilot assigns a value (numerical or otherwise) to the potential impact of the hazard, which qualifies the pilot's assessment of the hazard-risk.

- During each flight, the single pilot makes many decisions under hazardous conditions.

- To fly safely, the pilot must assess the degree of risk and determine the best course of action to mitigate it.

-

Assessing Risk:

- Assessment of risk is a crucial component of effective risk management. For example, the hazard of a nick in the propeller poses a risk only if the airplane is to fly. Suppose that the same damaged prop experiences constant vibration during regular engine operation. In that case, there is a high risk that it could fracture and cause catastrophic damage to the engine/or airframe, and passengers.

- Every flight has hazards and some level of risk associated with it. It is crucial that pilots, especially learners, can distinguish between low-risk and high-risk flights in advance and then establish a review process to develop risk mitigation strategies for flights throughout that range.

- For the single pilot, assessing risk is not as simple as it sounds. For example, the pilot acts as their own quality control in making decisions. A fatigued pilot who flew 16 hours may not feel too tired to continue. Most pilots are goal-oriented, and when asked to accept a flight, they tend to deny personal limitations while emphasizing issues not directly related to the mission. For example, pilots of helicopter emergency services (EMS) have (more than other groups) made flight decisions that add significant weight to the patient's welfare. These pilots weigh intangible factors (in this case, the patient) and fail to quantify actual hazards, such as fatigue or weather, accurately when making flight decisions. The single-pilot who has no other crew member for consultation must wrestle with the intangible factors that draw one into a precarious position. Therefore, they have a greater vulnerability than a whole crew.

- Examining National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) reports and other accident research can help a pilot learn to assess risk more effectively. For example, the accident rate during night visual flight rules (VFR) decreases by nearly 50 percent once a pilot reaches 100 hours and continues to decline until the 1,000-hour level. The data suggest that for the first 500 hours, pilots flying VFR at night might want to establish higher personal limitations than are required by the regulations and, if applicable, apply instrument flying skills in this environment.

- Several risk assessment models are available to aid in the risk assessment process. All taking slightly different approaches, the models seek a common goal of assessing risk objectively. The most basic tool is the risk matrix. It assesses two items: the likelihood of an event occurring and the consequence of that event.

-

Likelihood of an Event:

- The likelihood is about assessing the probability of a situation occurring. Likelihood is either probable, occasional, remote, or improbable, and these expressions denote varying degrees of likelihood. For example, a pilot is flying from point A to point B (50 miles) in marginal visual flight rules (MVFR) conditions. The likelihood of encountering potential instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) is the first question the pilot needs to answer. The experiences of other pilots, coupled with the forecast, might cause the pilot to assign "occasional" to determine the probability of encountering IMC.

- The following guidelines outline the process for creating assignments.

- Probable: an event will occur several times.

- Occasional: an event is likely to occur at some point in the future.

- Remote: an event is unlikely to occur, but is possible.

- Improbable: an event is highly unlikely to occur.

-

Severity of an Event:

- The next element is the severity or consequence of a pilot's action(s). It can relate to injury and/or damage. If the individual in the example above is not an instrument-rated pilot, what are the consequences of their encountering inadvertent IMC conditions? In this case, because the pilot is not IFR rated, the consequences are catastrophic. The following are guidelines for this assignment.

- Catastrophic: results in fatalities, total loss.

- Critical: severe injury, major damage.

- Marginal: minor injury, minor damage.

- Negligible: less than a minor injury, less than minor system damage.

- Simply connecting the two factors indicates the risk is high, and the pilot must either not fly or fly only after finding ways to mitigate, eliminate, or control the risk.

- The next element is the severity or consequence of a pilot's action(s). It can relate to injury and/or damage. If the individual in the example above is not an instrument-rated pilot, what are the consequences of their encountering inadvertent IMC conditions? In this case, because the pilot is not IFR rated, the consequences are catastrophic. The following are guidelines for this assignment.

-

-

Mitigating Risk:

- Risk assessment is only part of the equation. After determining the level of risk, the pilot must mitigate it. For example, the pilot flying from point A to point B (50 miles) in MVFR conditions has several ways to reduce risk:

- Wait for the weather to improve to good visual flight rules (VFR) conditions.

- Take an instrument-rated pilot.

- Delay the flight.

- Cancel the flight.

- Drive.

- One of the best ways single pilots can mitigate risk is to use the "IMSAFE" checklist to determine physical and mental readiness for flying:

- Illness: Am I sick? Illness is an obvious pilot risk.

- Medication: Are there any medications I'm taking that might affect my judgment or cause drowsiness?

- Stress: Am I under psychological pressure from the job? Do I have money, health, or family problems? Stress causes concentration and performance problems. While the regulations list medical conditions that require grounding, stress is not among them. The pilot should consider the effects of stress on performance.

- Alcohol: Have I been drinking within 8 hours? Within 24 hours? As little as one ounce of liquor, one bottle of beer, or four ounces of wine can impair flying skills. Alcohol also renders a pilot more susceptible to disorientation and hypoxia.

- Fatigue: Am I tired and not getting enough rest? Fatigue remains one of the most insidious hazards to flight safety, as it may not be apparent to a pilot until serious errors occur.

- Emotion: Am I emotionally upset?

- Risk assessment is only part of the equation. After determining the level of risk, the pilot must mitigate it. For example, the pilot flying from point A to point B (50 miles) in MVFR conditions has several ways to reduce risk:

-

-

Risk Management Decision-Making Process:

- Risk Management is a systematic decision-making process used to identify and manage hazards that pose a threat to resources.

- Risk Management is a tool used to make informed decisions by providing the best baseline of knowledge and experience available.

- The goal of risk management is to identify safety-related hazards and proactively mitigate the associated risks.

- When a pilot follows good decision-making practices, the inherent risk in a flight is reduced or even eliminated.

- Direct or indirect experience, as well as education, form the foundation for making informed decisions.

- The formal risk management decision-making process involves six steps. [Figure 4]

- Consider automotive seat belt use. In just two decades, seat belt use has become the norm, placing those who do not wear seatbelts outside the norm. However, this group may learn to wear a seatbelt through either direct or indirect experience.

- For example, if you are flying a new airplane for the first time, you might determine that the risk of making that flight in low visibility conditions is unnecessary.

- An indirect learning experience occurs when a loved one is injured during a car accident because they failed to wear a seat belt.

-

Principles of Risk Management:

-

Accept No Unnecessary Risk:

- Risk that carries no commensurate return in terms of benefits or opportunities is unnecessary.

- Flying is not possible without risk, but the most logical choices for accomplishing a flight are those that meet all requirements with minimum risk.

- Said differently, accept necessary risk.

- For example, if you are flying a new airplane for the first time, you might determine that the risk of making that flight in low visibility conditions is unnecessary.

-

Make Risk Decisions at the Appropriate Level:

- Anyone can make a risk decision; however, the person who can develop and implement risk controls should be the one to make risk decisions.

- Remember, decisions rest with the pilot-in-command, so never let anyone else, including ATC and your passengers, make risky decisions on your behalf.

- For example, in the maintenance facility, an aviation maintenance technician (AMT) may need to escalate decisions to the next level in the management chain upon determining that the controls available to them will not reduce residual risk to an acceptable level.

- Anyone can make a risk decision; however, the person who can develop and implement risk controls should be the one to make risk decisions.

-

Accept Risk When Benefits Outweigh Costs (dangers):

- Always compare the benefits of any flight to the identified costs.

- High-risk missions can be appropriate when there is clear knowledge that the sum of the benefits exceeds the sum of the costs.

- For example, a day with good weather is a much better time to fly an unfamiliar airplane for the first time than a day with low IFR conditions.

- Always compare the benefits of any flight to the identified costs.

-

Integrate Risk Management Into Planning At All Levels:

- It's best to manage risks in planning.

- In flight, risk decisions become more difficult.

- Expect in-flight decisions, but preserve bandwidth and concentration for those instances.

-

Risk Management Levels:

- Risk Management applies on three levels, based upon time and assets available:

-

Time-Critical:

- A quick mental review of the five-step process when there is insufficient time for any more (i.e., in-flight mission/situation changes).

-

Deliberate:

- Brainstorming in groups leverages collective experience to identify hazards (e.g., aircraft movement, takeoff, and landing).

-

In-Depth:

- More substantial tools are needed to thoroughly study the hazards and their associated risks, providing insight during complex operations (i.e., weapons detachment).

-

Operating Unfamiliar Aircraft or Avionics

- Pilots, especially renters, can find themselves operating aircraft that are either configured or equipped differently from those with which they're most familiar.

- Switches may be in different locations, familiar equipment may be missing, or technicians may have installed additional equipment.

- It is in a pilot's best interest to familiarize themselves either on the ground or with a lesson.

- Review different numbers and operating characteristics before flight, with any quick reference guide (provided or self-made) handy during flight.

- See also: aircraft transitions.

Confirmation/Expectation Bias

- Confirmation or expectation bias occurs when a pilot listens for a specific answer and hears what they expect, rather than what was actually said.

- Pilots risk falling victim to bias in every aspect of a flight, from planning through execution to debrief.

- To prevent falling victim to confirmation bias or expectation bias, pilots should avoid taking notes before receiving a clearance and read back what they heard in full.

Aeronautical Decision-Making Lessons & Case Studies

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Identification: CEN09PA348:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: the pilot’s decision-making, flight and duty times and rest periods, NMSP staffing, safety management system programs and risk assessments, communications between the NMSP pilots and volunteer search and rescue organization personnel, instrument flying, and flight-following equipment.

- National Transportation Safety Board Identification: ERA22LA120:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot’s inadequate preflight planning, inadequate inflight monitoring of the airplane’s flight parameters, and his failure to regain control of the aircraft following entry into an inadvertent aerodynamic stall. The pilot’s likely spatial disorientation following the aerodynamic stall also contributed to the outcome.

Aeronautical Decision-Making Knowledge Quiz

Aeronautical Decision-Making Conclusion

- Before there were flight instructors, there was instinct.

- ADM training cannot cover every situation, but using all available information and experience, pilots should make educated assumptions in the absence of certainty.

- Recognize and stay ahead of cascading situations.

- A low fuel situation can escalate into a diversion, which may lead to operations at an unfamiliar airport and subsequent complications.

- Remains cognizant of risk stacking/swiss cheese models whereby individual risks can compound to cause greater effects.

- Remember, ADM is a Special Emphasis Item in the Airman Certification Standards.

- Human factors and your day-to-day attitudes will dictate what you bring to the airplane.

- While poor decision-making in everyday life does not always lead to tragedy, the margin for error in aviation is thin.

- Since ADM enhances the management of an aeronautical environment, all pilots should become familiar with and employ ADM.

- Traditionally, pilots have been well-trained to react to emergencies; however, they are less prepared to make decisions that require a more reflective response, where greater analysis is necessary.

- Pilots must understand hazardous attitudes so they can be recognized, labeled as dangerous, and the appropriate antidote applied.

- The Federal Aviation Administration publishes a newsletter titled Callback.

- This newsletter, combined with reviews of past mishaps, will ensure you keep grounded to the basic principles and safety practices you learned as that young private pilot on their first solo.

- Go/no-go criteria are essential in making an initial determination on whether to proceed, but it is also a continuous process on when to alter a plan.

- It is important to reiterate that these models are not linear thought processes.

- The decision-making process is a continuous loop of perceiving, processing, and performing.

- The use of these models is initially formal but becomes secondary over time.

- At least five times before and during the flight, the pilot should review and consider the "Plan, the Plane, the Pilot, the Passengers, and the Programming" and make the appropriate decision required by the current situation. Failure to make a decision is a decision. Under SRM and the 5 Ps, even the decision to make no changes to the current plan requires careful consideration of all the risk factors present.

- Be very cautious when deviating from a routine, as that is where steps get missed and subsequent mistakes occur.

- See also: Crew Resource Management (CRM).

- Distractions and interruptions can severely compromise flight safety.

- Check out the FAA Safety Team's distraction management enhancement topic or AOPA's Training Tip: The Passenger Effect.

- Consider using a flight risk assessment tool, or FRAT, before the flight.

- Throughout the practical test, the evaluator must assess the applicant’s ability to use sound aeronautical decision-making procedures to identify hazards and mitigate risk.

- The evaluator must fulfill this requirement by referencing the risk management elements of the given Task(s) and by developing scenarios that incorporate and combine Tasks appropriate for assessing the applicant's risk management in making safe aeronautical decisions.

- For example, the evaluator may develop a scenario that incorporates weather decisions and performance planning.

- In assessing the applicant’s performance, the evaluator should take note of the applicant’s use of crew-resource management and, if appropriate, single-pilot resource management.

- CRM/SRM encompasses a set of competencies that includes situational awareness, communication skills, teamwork, task allocation, and decision-making, all within a comprehensive framework of standard operating procedures (SOP).

- SRM specifically refers to the management of all resources onboard the aircraft, as well as outside resources available to the single pilot.

- If an applicant fails to use aeronautical decision-making (ADM), including SRM/CRM, as applicable in any Task, the evaluator will note that Task as failed.

- The evaluator will also include the ADM Skill element from the Flight Deck Management Task on the Notice of Disapproval of Application.

- One of the most important concepts that safe pilots understand is the difference between what is "legal" in terms of the regulations and what is "smart" or "safe" in terms of pilot experience and proficiency (currency versus proficiency).

- Aeronautical decision-making resources are available on AOPA's Aeronautical Decision-Making Portal.

- Still looking for something? Continue searching:

Aeronautical Decision-Making References

- Advisory Circular (60-22) Aeronautical Decision-Making

- Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association - Do The Right Thing: Decision-Making for Pilots

- Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association - IFR Pilot Personal Minimums Contract

- Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association - VFR Pilot Personal Minimums Contract

- Federal Aviation Administration - Instrument Flying Handbook (1-15) Aeronautical Decision-Making (ADM)

- Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association - Training Tip: Getting to No

- Federal Aviation Administration - Callback

- Federal Aviation Administration - Personal Minimums Worksheet

- Federal Aviation Administration - Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge

- Federal Aviation Administration - Aviation Safety - Pilot Proficiency Training

- Federal Aviation Administration - Pilot/Controller Glossary

- Federal Aviation Administration - Safety Briefing: Aeronautical Decision-Making

- Federal Aviation Administration Safety Team - Aeronautical Decision Making