Steep Turns

Steep Turns develops the ability to recognize changes in aircraft flight characteristics and control effectiveness at steep turn angles.

Introduction to Steep Turns

- Steep turns develop a pilot's skill in flight control, smoothness, and coordination at high angles of bank; awareness of the airplane's orientation relative to external references; division of attention between flight-control applications; and the constant need to scan for hazards and other traffic in the area.

- Maximum performance turns are using the fastest rate of turn and the shortest radius.

- These turns will cause a much higher stalling speed.

- Limiting the load factor determines the maximum bank angle without stalling.

- Review your knowledge against the Private Pilot (Airplane) or Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Airman Certification Standards, and close out with a topic summary.

Steep Turns Overview

- Steep turns consist of single to multiple 360° and 720° turns, in either or both directions, using a bank angle between 45° and 60°

- Steep turns are primarily a training maneuver.

- Steep turns help pilots understand:

- Higher G-forces during a turn.

- An airplane's inherent tendency to overbank when the bank angle exceeds 30°

- The significant loss of the vertical component of lift at steep bank angles.

- Substantial pitch control pressures.

- The need for additional power to maintain airspeed during the turn.

- Still, pilots could find themselves in situations requiring high-performance turns, such as unexpected obstacle avoidance or emergencies (e.g., steep spirals).

Steep Turns Performance Review

- To fully appreciate steep turns, a full review of turn performance is required.

- These principles include:

-

Turn Performance Review:

- When an airplane banks for a level turn, the lift vector tilts, creating both vertical and horizontal components.

- To maintain altitude at a constant airspeed, the pilot increases the angle of attack (AOA) to ensure the vertical component of lift remains sufficient.

- The pilot adds power as needed to maintain airspeed.

- For a steep turn, as in any level turn, the horizontal component of lift provides the necessary force to turn the airplane.

- For any aircraft at any airspeed, a given bank angle in a level turn always produces the same load factor.

-

Rate and Radius of Turns Review:

-

Rate of Turn:

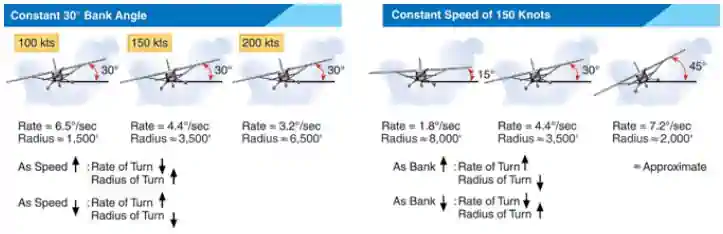

- The rate depends on a set bank angle at a set speed. [Figure 2]

- The standard rate of turn is 3° per second.

-

Speed & Rate of Turn:

- If the aircraft increases speed without changing the bank angle, the rate of turn decreases.

- If the aircraft decreases speed without changing the bank angle, the rate of turn increases.

-

Bank Angle & Rate of Turn:

- If the aircraft bank angle increases without changing airspeed, the rate of turn increases.

- If the aircraft bank angle decreases without changing airspeed, the rate of turn decreases.

- Speed and bank angle, therefore, vary inversely to maintain a standard rate of turn.

- This relationship becomes significant in the instrument environment, such as during holding or an instrument approach.

- A rule of thumb for determining the standard rate turn is to divide the airspeed by ten and add 5.

- Example: an aircraft with an airspeed of 90 knots takes a bank angle of 16° to maintain a standard rate turn (90 knots ÷ 10 + 5 = 14°).

-

Radius of Turn:

- The radius of turn varies with changes in either speed or bank. [Figure 2]

-

Speed & Radius of Turn:

- If the speed increases without changing the bank angle, the radius of turn increases.

- If the speed decreases without changing the bank angle, the radius of turn decreases.

-

Bank Angle & Radius of Turn:

- If the speed is constant, increasing the bank angle decreases the radius of turn.

- If the speed is constant, decreasing the bank angle increases the radius of turn.

- Therefore, intercepting a course at a higher speed requires more distance and, therefore, requires a longer lead.

- If the speed is slowed considerably in preparation for holding or an approach, a shorter lead is needed than that required for cruise flight.

-

-

Load Factor Review:

- The load factor is the vector addition of the gravitational and centrifugal forces an aircraft experiences.

- When the bank angle is steep, as in a level altitude 45° banked turn, the resulting load factor is 1.41.

- In a level altitude 60° banked turn, the resulting load factor is 2.0.

- To put this in perspective, with a load factor of 2.0, the aircraft's effective weight (including its occupants) doubles.

- Pilots may have difficulty with orientation and movement when first experiencing these forces.

- Pilots should also understand that load factors increase dramatically during a level turn beyond 60° of bank.

- Note that the design of a standard category general aviation airplane accommodates a load factor up to 3.8. A level turn using 75° of bank exceeds that limit.

- Because of higher load factors, pilots perform steep turns at airspeeds that do not exceed the airplane's design maneuvering speed (VA) or operating maneuvering speed (VO).

- Maximum turning performance for a given speed is when an aircraft has a high angle of bank.

- Structural and aerodynamic design, along with available power, limit each airplane's level-turning performance.

- The airplane's limiting load factor sets the maximum bank angle it can maintain in level flight without exceeding structural limits or stalling.

- As the load factor increases, so does the stalling speed.

- For example, if an aircraft stalls in level flight at 50 knots, it will stall at 60 knots in a 45° steep turn while maintaining altitude.

- The aircraft will stall at 70 knots if the bank increases to 60°.

- Stalling speed increases at the square root of the load factor.

- As the bank angle increases in level flight, the margin between stalling speed and maneuvering speed decreases.

- At speeds at or below VA or VO, the airplane will stall before exceeding the design load limit.

- The load factor is the vector addition of the gravitational and centrifugal forces an aircraft experiences.

-

Overbanking Review:

- In addition to the increased load factors, the aircraft will exhibit an "overbanking tendency."

- In most flight maneuvers, bank angles are shallow enough that the aircraft exhibits positive or neutral longitudinal stability.

- However, as the bank angle increases, the airplane will continue to roll in the direction of the bank unless the pilot deliberately applies opposite aileron pressure.

- Pilots should also be mindful of the various left-turning tendencies, such as P-factor, which require effective rudder/aileron coordination.

- During a steep turn, the airplane experiences a significant yaw component that creates motion toward and away from the Earth’s surface, which can seem confusing at first.

- Before starting any practice maneuver, the pilot ensures that the area is clear of air traffic and other hazards.

- Additionally, the pilot should choose distant references to help determine when to begin rolling out of the turn.

-

Coordination Throughout Turns:

- A slipping turn occurs when the aircraft does not turn at the rate appropriate to the bank, and it falls to the inside of the turn. [Figure 3]

- The aircraft is banked too much for the rate of turn, so the horizontal lift component exceeds the centrifugal force.

- A skidding turn results from an excess of centrifugal force over the horizontal lift component, pulling the aircraft toward the outside of the turn. [Figure 3]

- The rate of turn is too great for the angle of bank, so the horizontal lift component is less than the centrifugal force.

- The ball instrument indicates the quality of the turn and should be centered when banking.

- If the ball is off-center toward the turn, the aircraft is slipping, requiring increased rudder pressure on that side to increase the rate of turn.

- Also, reducing the bank angle without changing the rudder pressure will help coordinate the turn.

- If the ball is off-center on the side away from the turn, the aircraft is skidding, requiring rudder pressure on that side to be relaxed to decrease the rate of turn.

- Also, increasing the bank angle without changing the rudder pressure will help coordinate the turn.

- The ball should be centered when the wings are level; use rudder and/or aileron trim if available.

- The increase in induced drag (due to the angle of attack increase required to maintain altitude) results in a minor loss of airspeed if the power setting is not adjusted.

- Note that in a slip, the outside wing experiences slower movement through the air, resulting in a higher angle of attack to maintain lift.

- In the event of a stall, the aircraft will then roll to the outside wing (due to a higher angle of attack).

- The reverse is true for a slip, where the inside wing drops first due to the relatively slower movement through the air.

Steep Turns Procedure

- Perform clearing turns.

- Select a prominent visual reference point ahead of the airplane and out toward the horizon.

- Adjust the pitch and power to maintain altitude.

- Trim as necessary.

- Maintain heading and note the pitch attitude required for level flight.

- After establishing the manufacturer's recommended entry speed, VA, or VO, as applicable, smoothly roll into a predetermined bank angle between 45° and 60°

- While establishing the bank angle, generally before 30° of bank, smoothly apply elevator back pressure to increase the AOA.

- Considerable force is required on the elevator control to maintain level flight.

- The decision to use trim depends on the airplane's characteristics, the speed of the trim system, and the preferences of the instructor and learner.

- Simultaneously, power should be applied.

- As the AOA increases, so does drag, and additional power allows the airplane to maintain airspeed.

- Remain coordinated.

- Remember parallax error.

- While establishing the bank angle, generally before 30° of bank, smoothly apply elevator back pressure to increase the AOA.

- Rolling through 30° of bank, increase power to maintain airspeed.

- Increase pitch to maintain altitude.

- Trim as necessary.

- Pulling back on the yoke will increase the rate of turn, but do not allow the aircraft to climb.

- Refer to the visual reference point and roll out 20-25° before the entry heading.

- Through 30° of bank, decrease RPM.

- Decrease pitch.

- Trim nose down.

- Return to wings level on entry heading, altitude, and airspeed.

- A good rule of thumb is to begin the rollout at 1/2 the bank angle before reaching the terminating heading.

- For example, if a steep turn begins on a heading of 270° and the bank angle is 60°, the pilot should begin the rollout 30° before the entry heading.

- While the rollout is underway, gradually reduce the elevator back pressure, trim (if used), and power as necessary to maintain altitude and airspeed.

- A good rule of thumb is to begin the rollout at 1/2 the bank angle before reaching the terminating heading.

- Immediately roll into a bank in the opposite direction.

- Perform the maneuver once more in the opposite direction.

- Upon rolling out after the second turn, resume normal cruise.

- Trim as necessary.

- Complete the cruise checklist.

Steep Turns Common Errors

- Failure to adequately clear the area.

- Inadequate back-elevator pressure control as power reduces, resulting in altitude loss.

- Excessive back-elevator pressure as power reduces, resulting in altitude gain, followed by a rapid reduction in airspeed and "mushing."

- Remember, the aircraft stalls at a higher airspeed when in high angles of bank.

- Inadequate compensation for adverse yaw during turns.

- Inadequate power management.

- Inability to adequately divide attention between airplane control and orientation.

- Inadequate pitch control on entry or rollout.

- Failure to maintain a constant bank angle.

- Poor flight control coordination.

- Ineffective use of trim.

- Ineffective use of power.

- Inadequate airspeed control.

- Becoming disoriented.

- Performing by reference to the flight instruments rather than visual references.

- Failure to scan for other traffic during the maneuver.

- Attempting to start recovery prematurely.

- Failure to stop the turn on the designated heading.

Steep Turns Lessons & Case Studies

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Identification: CEN20LA357:

- The NTSB determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot's failure to maintain airspeed while maneuvering at low altitude, which resulted in an aerodynamic stall and collision with terrain.

Steep Turns Conclusion

- Remain mindful that performance calculations are usually more optimistic than actual performance.

- As PilotWorkshops state: "Steep turns demonstrate turn performance while practice division of attention, orientation, comfort with higher G-forces, overbanking tendency, and learning the control inputs required to maintain altitude at a constant airspeed during the turn."

- Consider actual versus realized performance when doing any performance calculations.

- Consider practicing maneuvers on a flight simulator to introduce yourself to maneuvers or knock off rust.

- Still looking for something? Continue searching: