The Eyes & Vision

Vision is the most relied-upon sense for developing a pilot's situational awareness in the aviation environment, but it can also be the source of confusion.

Introduction to the Eyes and Vision

- Of the body's senses, vision is the most important for safe flight.

- This tool provides the pilot with the most sensory information from which to pilot the aircraft.

- Understanding the limitations of the eye is crucial for a pilot's ability to adapt to various conditions.

How the Eyeball Works

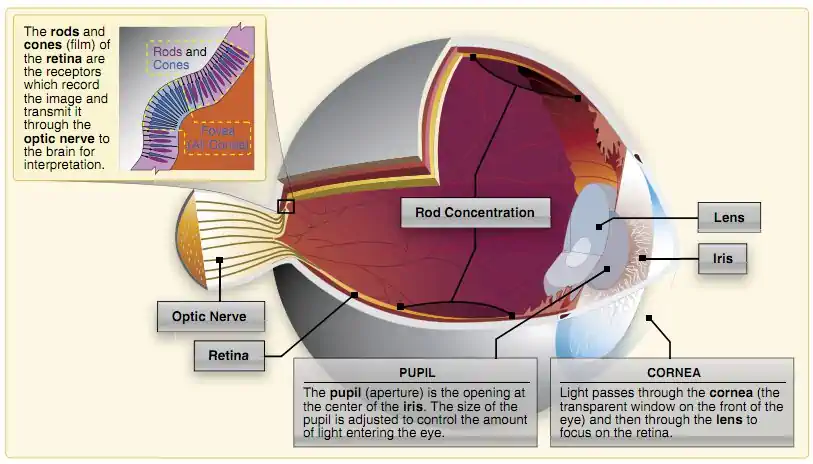

- Light enters the eyeball through the cornea at the front of the eye.

- The light then continues through the pupil, which adjusts the amount of light allowed to enter the eye.

- Focused light finally reaches the retina at the back of the eye.

- The retina takes the concentrated light and, through cells, converts light energy into electrical impulses for the brain to interpret.

- The brain assigns color based on many items, to include an object's surroundings

- The eye interprets light with an array of "rods" and "cones."

-

Rods:

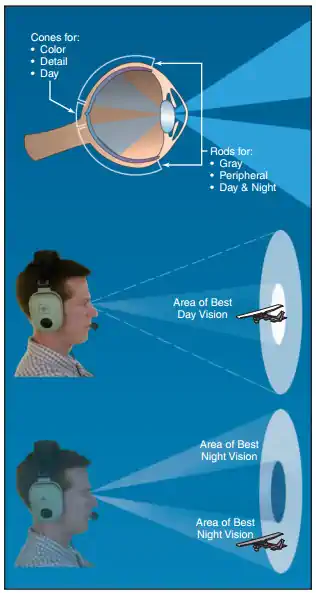

- The rods on the retina concentrate in a ring around the cones.

- There are virtually no rods at all in the center of the eye, resulting in a blind zone.

- Rods are unable to discern color but are sensitive to low light, making them critical for low-light conditions.

- Because rods are mostly away from the fovea, they are responsible for handling peripheral vision, requiring pilots to look off-center to see objects at night.

- In the absence of normal light, the process of night vision is placed almost entirely on the rods.

- They detect objects (shapes), particularly those that are moving, but do not give detail or color, only shades of gray.

- It contains rhodopsin, also known as visual purple, which is particularly sensitive to light.

- Once fully adapted to darkness, the rods are 10,000 times more sensitive to light.

- Low acuity.

-

Cones:

- The cones on the retina are responsible for perceiving all colors, fine detail, and objects at a distance.

- Cones are most concentrated toward the center of the field of vision.

- Function in day and night (moonlight), but optimized for day.

- Unlike at night, objects are best visible when viewed directly.

- High acuity.

- While the eyes can observe an approximate 200° arc of the horizon at one glance, only a tiny center area called the fovea, located at the back of the eye, can send clear, sharply focused messages to the brain.

- All other visual information that is not processed directly through the fovea will be of less detail.

- The fovea attaches to the retina, creating a blind spot.

- Beware of parallax error when attempting to read needles or trim the ball, etc.

Night Vision and Dark Adaptation

-

Night Vision:

- The difference between night and day vision is the presence of cones and rods. [Figure 2]

- Both sit at the back of the eye or retina, the layer that focuses all images.

- These nerves connect to the cells of the optic nerve, which transmits messages directly to the brain.

- Both rods and cones support vision during daylight, and while their functions overlap, rods are primarily responsible for night vision.

- The difference between night and day vision is the presence of cones and rods. [Figure 2]

-

Dark Adaptation:

- Dark adaptation allows the eyes to adjust to low light levels.

- Consider entering a darkened movie theater where you can't see anything initially, but as time goes on, your eyes adjust to the point where the features on the walls or seats start to stand out.

- Bright light reverses this process when you step outside, forcing you to shade your eyes.

- Process:

- The pupils of the eyes first enlarge to receive as much of the available light as possible.

- After about 5 to 10 minutes, the cones adjust to the dim light, making the eyes 100 times more sensitive than before entering the dark room.

- The rods take about 30 minutes to adapt to darkness, but when they do, they become approximately 100,000 times more sensitive to light than they were in the lighted area.

- A pilot can achieve a moderate degree of dark adapation within 30 minutes under dim red flight deck lighting.

- Any bright light, such as a room or a headlight, can disrupt night adaptation in as little as 10 seconds.

- Pilots should close one eye when using a light to preserve some degree of night vision.

- Temporary blindness, caused by an unusually bright light, may result in illusions or after-images until the eyes recover from the brightness.

- This results in misjudging or incorrectly identifying objects, such as mistaking slanted clouds for the horizon or populated areas for a landing field.

- Vertigo causes a feeling of dizziness and imbalance that can create or increase illusions.

- The illusions seem very real, and pilots of all skill levels can be affected.

- Under conditions of dim illumination, aeronautical charts and aircraft instruments can become unreadable unless adequately lit.

- Conversely, too much light can hinder an outside scan for other traffic and landmarks.

- During night flights near lightning, pilots should increase the brightness of the flight deck lights to prevent losing night vision from the bright flashes.

- Using a white lens flashlight can ruin adaptation, while using a red lens or green lens flashlight can wash out those colors on a map.

- You must use lighting conservatively.

- Exposure to cabin pressure altitudes above 5,000', carbon monoxide from smoking, a Vitamin A deficiency, and prolonged bright sunlight impair dark adaptation.

- Additional Notes:

- Adapt the eyes to darkness before flight and maintain the adaptation.

- If oxygen is available, use it during night flying.

- Do not wear sunglasses after sunset.

- Move the eyes more slowly than in daylight.

- Blink the eyes if they become blurred.

- Concentrate on seeing objects.

- Force the eyes to view off-center.

- Maintain good physical condition.

- Avoid smoking, drinking, and using drugs that may be harmful.

- Avoid keeping the interior lights on longer than necessary.

- If the eyes become blurry, blinking may refocus the lens.

- Dark adaptation allows the eyes to adjust to low light levels.

Visual Limitations & Impairments

- Smoking, alcohol, oxygen deprivation (hypoxia), diet, medication, and age affect vision, especially during night operations.

- Vision at night is impaired based on physical limitations.

- Knowing these limitations (rods vs. cones) is essential to improving vision.

- Dust.

- Fatigue.

- Emotion.

- Germs.

- Fallen eyelashes.

- Age

- Good eyesight depends upon physical condition.

- Optical illusions.

- Alcohol.

- Atmospheric conditions.

- Windscreen distortion.

- Oxygen.

- Acceleration.

- Glare.

- Heat.

- Lighting.

- Aircraft design.

- The "mind" (daydreaming).

-

Visual Limitations:

-

Empty Field Myopia:

- Empty Field Myopia, sometimes called Empty Space Myopia, is a condition in which the eyes, having nothing specific within the available visual field upon which to focus, focus automatically at a range of the order of a few feet ahead.

- This condition typically occurs when flying above the clouds or in a haze layer that provides no specific features to focus on outside the aircraft.

- Under these conditions, the pilot's eyes relax and focus on a comfortable distance, which may range from 10 to 30 feet.

- The pilot is looking without seeing.

- Pilots will struggle to focus on distant objects.

- To combat this, focus the eye on infinity (something well outside the cockpit) and maintain a consistent scan.

- You must refocus the eye each time you look in and then back out.

-

-

Parallax Error:

- A change in viewing position causes the apparent displacement of an object, known as parallax error.

- This error occurs to some extent when viewing an analog instrument from any direction other than directly head-on.

- Regarding reading instruments, digital displays correct for this error.

- Despite digital instruments, there remain backup analog instruments that may be even farther away (i.e., more parallax error) on the dashboard.

- Parallax error also affects the way a pilot views the outside world in flight, most pronounced during turns in aircraft with side-by-side seating (the pilot is seated on either side of the longitudinal axis).

- Assuming the pilot is sitting in the left seat and entering a left turn, the nose appears to rise.

- If, however, the pilot is in the same left seat and performs a turn to the right, the nose seems to fall.

- This error results in either an instinctual push down on the stick with a turn to the left (altitude loss) or a pull-back on a turn to the right (altitude gain).

- To overcome this error, the pilot must first be aware of the illusion to avoid improper inputs while maintaining an instrument scan to backup inputs.

-

Blind Zones:

- The day blind spot is on the optic nerve, where there are no light receptors.

- The night blind spot is due to the concentration of cones in an area surrounding the fovea on the retina.

- Because there are no rods here, directly looking at an object will cause it to disappear; therefore, you must offset where you are looking.

-

Visual/Night Illusions:

- Of the senses, vision is the most important for safe flight.

- However, various terrain features and atmospheric conditions can create optical illusions.

- These illusions are primarily associated with landing.

- Since pilots must transition from reliance on instruments to visual cues outside the flight deck for landing at the end of an instrument approach, they must be aware of the potential problems associated with these illusions and take appropriate corrective action.

-

False Horizon:

- Low-light nights tend to eliminate reference to a visual horizon.

- Sloping cloud formations, an obscured horizon, a dark scene spread with ground lights and stars, and specific geometric patterns of ground light can create the illusion of not being aligned with the horizon.

- Geometric patterns of ground light can create illusions that the light is not aligned correctly with the actual horizon.

- The disoriented pilot will align with an incorrect horizon and, hence, a dangerous attitude.

- As a result, pilots need to rely less on outside references at night and more on flight and navigation instruments.

-

Autokinesis:

- Caused by staring at a single point of light against a dark background for more than a few seconds.

- After a few moments, the light appears to move on its own.

- The disoriented pilot will lose control of the aircraft as they attempt to align it with the light.

- To prevent this illusion, focus your eyes on objects at varying distances and avoid fixating on a single target.

- Be sure to maintain a typical scan pattern.

-

Vertigo:

- A feeling of dizziness and disorientation caused by doubt in visual interpretation.

- Distractions and problems can result from a flickering light in the cockpit, anti-collision light, strobe lights, or other aircraft lights, and can cause flicker vertigo.

- Often experienced due to a lack of a well-defined horizon.

- Also experienced leaving a well-lit area (a runway) into darkness.

- Possible physical reactions include nausea, dizziness, grogginess, unconsciousness, headaches, or confusion.

-

Black-hole Approach:

- When landing at night from over water or non-lighted terrain, the runway lights are the only source of light.

- Without peripheral visual cues to help, pilots will have trouble orienting themselves relative to Earth (horizon).

- The runway can appear to be out of position (down-sloping or up-sloping) and, in the worst case, result in landing short of the runway.

- Utilize visual glide-slope indicators, if available.

- If navigation aids (NAVAIDs) are unavailable, pilots should pay careful attention to using the flight instruments to assist in maintaining orientation and a normal approach.

- Difficulty judging distance and distinguishing approach from runway lights further complicates night landings:

- Bright runway and approach lighting systems, particularly in areas with limited lighting, may create the illusion of a shorter distance to the runway, leading to a higher-than-normal approach angle.

- When flying over terrain with only a few lights, the runway will appear to recede or appear farther away, leading to a lower-than-normal approach.

- If the runway is near a city on higher terrain in the distance, the tendency will be to fly a lower-than-normal approach.

- A good review of the airfield layout and boundaries before initiating any approach will help the pilot maintain a safe approach angle.

- For example, when a double row of approach lights meets the boundary lights of the runway, there can be confusion about where the approach lights end and the runway lights begin.

- Under certain conditions, approach lights can make the aircraft seem higher in a turn to final than when its wings are level.

- The pilot should execute a go-around if they are unsure of their position or altitude at any time.

- The black-hole illusion is not just a problem for approaches, but also for departures.

- See also: AOPA Air Safety Institute - Safety Quiz: IFR Into a Black Hole.

Use of Sunglasses

- The FAA recommends that pilots use sunglasses with Ultraviolet (UV) protection to safeguard their eyes from the sun and to assist in locating other traffic, while minimizing color distortion.

- Pilots should avoid wearing polarized sunglasses, as they can interfere with instrumentation, making it difficult to see.

- You can easily find sunglasses on Amazon.

Vision Conclusion

- Even though the human eye is optimized for day vision, it is also capable of vision in very low light environments.

- Visual cues often prevail over false senstation sfrom other sensory systems, making their loss significant when flying in Instrument Meterological Conditions.

- This is where trusting flight instruments is key.

- Realize that in most instances, flying at night is also toward the end of one's day, allowing fatigue and visual stressors to have already taken a toll on overall visual acuity.

- Still looking for something? Continue searching:

The Eyes and Vision References

- Federal Aviation Administration - Pilot/Controller Glossary.

- Aeronautical Information Manual (8-1-6) Vision in Flight.

- Airplane Flying Handbook (10-1) Night Vision.

- FAA - (OK-13-0170) Sunglasses for Pilots: Beyond the Image.

- Instrument Flying Handbook (1-2) Eyes.

- Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (16-17) Vision in Flight.

- Skybrary - Empty-Field Myopia.