Emergency Procedures

Emergency procedures are taken by aviation operators to identify, assess, and address an emergency situation.

Introduction to Emergency Procedures

- The PIC is directly responsible for and is the final authority regarding the operation of that aircraft.

- Pilots must be prepared to act in the event of an abnormal condition (abnormalities not time-threatening) or an emergency (immediate action required).

- In an emergency requiring immediate action, the pilot-in-command and remote pilot-in-command may deviate from FAR 91 or FAR 107, respectively, to the extent required to meet the emergency.

- If the PIC chooses to deviate from the provisions of an ATC clearance, the PIC must notify ATC as soon as possible and obtain an amended clearance.

- Note this is not a blanket clearance to perform unnecessary deviations!

- Unless deviation is necessary under the emergency authority of 91.3, pilots of IFR flights experiencing two-way radio communication failure are expected to adhere to the procedures prescribed under "IFR operations, two-way radio communications failure."

- If the PIC chooses to deviate from the provisions of an ATC clearance, the PIC must notify ATC as soon as possible and obtain an amended clearance.

- Troubleshooting is important, but don't fix an airplane airborne when you can safely land first.

- Be directive; if you want something, tell them, and don't let ATC drive you.

- Declare emergencies with general terms; use "electrical" or "engine," for example.

- The PIC must notify ATC as soon as possible and obtain an amended clearance.

- Discrete emergency frequencies may be assigned by ATC.

- By default use CTAF or guard (121.5/243.0).

- You must hear different radio communications.

- Emergency hand signals are listed in 6-5-3.

- First 3 seconds, ask yourself, where am I? What do I have? Is the light valid?

- With every emergency, there will be primary and secondary signals.

- It is important to realize that secondary indications may or may not be present.

Emergency Procedures

- ALWAYS:

- Aircraft control - MAINTAIN.

- Precise nature of problem - DETERMINE.

- Applicable emergency procedures - EXECUTE.

- Appropriate landing criteria - DETERMINE AND EXECUTE.

- As always, the most important emergency procedure you can ever remember is to aviate, navigate, and then communicate.

- These three steps are continuous processes that never stop, requiring pilot judgment to prioritize steps.

-

Aviate:

- Complete any immediate action procedures that may be required.

- Reduce the electrical load, as required, to buy yourself time.

- Position the aircraft in the best position to address the emergency, such as "climbing to cope."

- After the situation is under control, and while navigating/communicating, open Chapter 7 of the POH and begin going through the emergency procedure steps, starting back at step 1.

-

Communicate:

- Contact ATC if able.

- If you have not already had to address your passengers, take the time to do so now.

- If you have a handheld radio, break it out and attempt to establish radio communication with a local agency.

- While less reliable but more predominant, reach for your cell phone and attempt calling ATC.

- With this option in mind, remember that fumbling to find the phone number while in flight is going to be distracting and could make the situation much worse, causing distraction and possibly loss of situational awareness.

- Consider loading your phone with the appropriate telephone numbers a step in preflight.

-

Troubleshooting

- Request block altitudes and orbit on the approach end, offset to the runway of the intended landing if possible.

- Climb above the weather if possible.

- If contacting base or an FBO, start with what you have, what you've done, and what page you're now on.

- Consider the remaining fuel for the urgency of getting the aircraft on deck.

- Receiving vectors it is a good idea to constantly repeat headings and altitudes are you are busy and it is easy to forget.

Types of Emergencies

- Immediate Action: do as quickly as possible consistent with flying (aviating, navigating, communicating).

- Non-Immediate Action: Get to them when you get to them.

Emergency Notification

- Emergency notification may come in several forms including aural, visual, or tactical.

-

Aural:

- Alarms may be utilized with more advanced avionics.

- Alerts are intended to cause people to stop what they are doing and attend to a potential hazard. However, some alerts fail to provide useful information and can create their own human factors problems. These are known as nuisance alerts (Sanquist, Thurman, & Mahy, 2005). Nuisance alerts are troubling because the person receiving the alert must devote attention to deciding if the alert is valid and whether action is necessary.

What to do?

- Breathe and determine what is going on.

- Panic is no solution.

- Prioritize emergencies (if compounding).

- Point to field/Immediate Action.

- Climb, if possible, to improve communication and radar coverage.

- Note that you cannot climb unauthorizedly in IFR.

- Continue squawking the same code under radar coverage; if unable to contact ATC, squawk 7700, and this can keep you free from violations, though an explanation may be requested later.

- Orbit near field in VMC.

Declaring an Emergency

- Pilots may declare an emergency when, in their estimation, additional services and prioritization are required to resolve a situation.

- Additionally, controllers may declare an emergency an emergency on behalf of the pilot when they believe the pilot is in a situation that requires priority handling.

- Declaring an emergency provides additional ground support, resources, and priority handling.

- Pilots are not punished for declaring an emergency when, in their judgment, it is warranted.

- Pilots can expect to be contacted by the FAA to explain their situation so they can gather data; admitting a mistake is an acceptable answer!

Powerplant Malfunctions & Emergencies

- Powerplant emergencies can range from minor degradation to all-out engine failure.

- Engines run on air and fuel.

- Since air is practically a given, when an engine fails benignly, suspect a fuel issue.

- The FAA published advisory circular 20-105 to provide recommendations on best practices to prevent accidents.

- Regardless, treat everything as if it will lead to an engine failure

- Consider thinking of the memory aid: glide, grass, and gas.

-

Catastrophic Engine Failure:

- Although uncommon, catastrophic engine failures are when an engine comes apart in flight.

- Any oil that escapes the cowling and impacts the windscreen is likely to blur the windscreen and won't simply blow off.

- In this instance, enhanced vision systems are life-savers.

- When selecting an off-airport landing site, consider: wind, space, obstacles, and surface condition.

- Consider the memory aid of "A-B-C-D-E" whereby you pitch for AIRSPEED, fly at BEST GLIDE, run the CHECKLIST, and finally DECLARE AN EMERGENCY, as appropriate, and EXECUTE the landing.

- Pilots should not conduct simulated engine failures below 500' AGL or as prescribed by FAR 91.119, whichever is higher.

- Likewise, simulated landings should not be continued below 5,00' AGL unless at an approved airport where the aircraft is in a position to land and the landing will not interfere with other traffic.

- Some avionics provide glide rings to inform the pilot what is and is not within a range based on altitude, aircraft performance, environment, etc.

-

High Cylinder Head Temperature:

- High temperatures of any kind are cause for concern.

- High cylinder head temperatures are cause for concern about your engine.

-

High Cylinder Head Temperature Indications:

- Your cylinder head temperature gauge will operate higher than normal, though not yet necessarily in a 'red' area.

-

High Cylinder Head Temperature Secondary Indications:

-

High Cylinder Head Temperature Considerations:

- Insufficient air is getting into the engine cowling calling for reduced pitch, increased speed, open cowl flaps, or a removal of a blockage.

- Improper fuel-to-air mixture ratio (lean mixtures could run hotter).

- Equipment failure (spark plugs, magnetos).

- Expect engine power to decrease.

- Expect engine oil consumption to increase.

- Left uncorrected, detonation and pre-ignition may start occurring, exacerbating the problem.

-

Engine Failure:

- With engine failures, speed (trading speed for altitude) is life, and altitude (time) is life insurance.

- Engine failures are largely due to mechanical failure, loss of spark, loss of air, or loss of fuel.

- Engine failures require immediate action.

- You should always have a plan based on the phase of the flight before you take off.

-

Engine Failure Primary Indications:

- Dropping, low, or no RPM.

-

Engine Failure Secondary Indications:

- Dropping temperatures and pressures.

- Reduced noise from the engine.

-

Engine Failure Considerations:

- Consider an action just performed may be the source of the problem.

- There may be enough time to restart the engine.

- Altitude is important, but without the appropriate airspeed you will lose too much altitude or stall.

- As part of takeoff, engine failure must be discussed in as much detail as practical with altitudes and turning limitations.

- Electrical abnormalities may distract the pilot from engine abnormalities, leading to improper immediate action procedures.

- Following an engine failure, you will lose several systems, such as the vacuum system, which will result in a partial panel situation.

- Loose mixture controls may slowly move to idle.

- Sometimes, the engine is receiving too much fuel (esp. at higher altitudes), resulting in a flooded engine that requires leaning, counter to most conventional engine failure immediate actions.

- A partially open primer allows raw fuel to get into the engine intake without atomizing as required for proper combustion.

- Loss of the alternator will mean you're running off battery power, which is limited to the condition of the battery.

- If conducting an off-field landing, remember that magneto wires can break, leading to a hot mag.

- Make your landing crash as slow and as controlled as possible.

- Deceleration impacts increase as the square of the speed.

- Impact forces at 60 kts are four times those at 30 kts.

- At 45 kts only 9.4 feet of deceleration will bring you to a stop.

- Deceleration impacts increase as the square of the speed.

- Consider requesting the runway to be foamed to avoid a fire upon landing, as available.

- Losing situational awareness and stalling the aircraft is far more lethal than the emergency landing.

- Engine Failure on Takeoff:

- Pilots must have a plan for engine failure on takeoff before they take the runway.

- Failure to obtain and/or maintain flying speed is a leading cause of accidents, so fly the aircraft at the appropriate speed first and foremost.

- Turning back to the departure runway (often referred to as the impossible turn) is a highly dangerous maneuver.

- The FAA now states matter-of-factly in Advisory Circular 61-83J that flight instructors should demonstrate and teach trainees when and how to make a safe turnback to the field after an engine failure.

- The impossible turn is only impossible if you do not have the performance, so know when you do, and practice-don't guess!

- Every factor impacts the performance required to successfully turnaround and land after takeoff, requiring careful consideration as to conditions practiced and conditions faced.

- Whether you can do a turnaround is dependent on the aircraft's climb relative to glide performance.

- The closer they are, the better chance you can perform the maneuver, but the glide ratio is not all there is to consider.

- Aircraft that climb and glide at relatively higher airspeeds will be further from the airport and eat up more distance in the turns, resulting in a reduced likelihood of success.

- Pilots have a tendency to get uncoordinated when turning fast to be able to see the runway.

- This turn in and of itself increases accelerated stall speed and, therefore, risk.

- Turn direction should be into the wind and briefed as much on the takeoff brief.

- Part of the brief should also include whether a turnback is even an option.

- Note that the best glide speed changes with weight, but the range will remain constant to the technique performed.

- Be sure to feather (if available) the propeller.

- In multi-engine aircraft, use a call-out similar to "Identify, Verify, Feather" where identify is putting your hand on the feather for the correct engine, verifying is verification (potentially from another crewmember, and feather is the action.

-

Night Considerations:

- Flying higher provides more time and range to solve the problem or find a safe location for landing.

- Consider checkpoints along the route that favor landing spots (i.e., airports).

- Spatial disorientation may be more likely if panicked, moving fast, etc.

- Tree landings are more survivable than many would expect

- Consider the use of synthetic vision when possible.

- Pilot Workshops provides a night landing scenario with considerations in an emergency landing with no light.

-

Multi-Engine Considerations:

- If an engine catches fire, it will generate less power until failure, resulting in a sudden yaw.

-

Engine Failure Prevention:

- Ensure sufficient fuel quantity (between all tanks), type.

- Avoid changing fuel tanks (on selector-driven aircraft) away from suitable ditch points.

- Mark navlogs when fuel selectors are swapped.

- Minimize actions that could foul spark plugs, like running excessively rich.

-

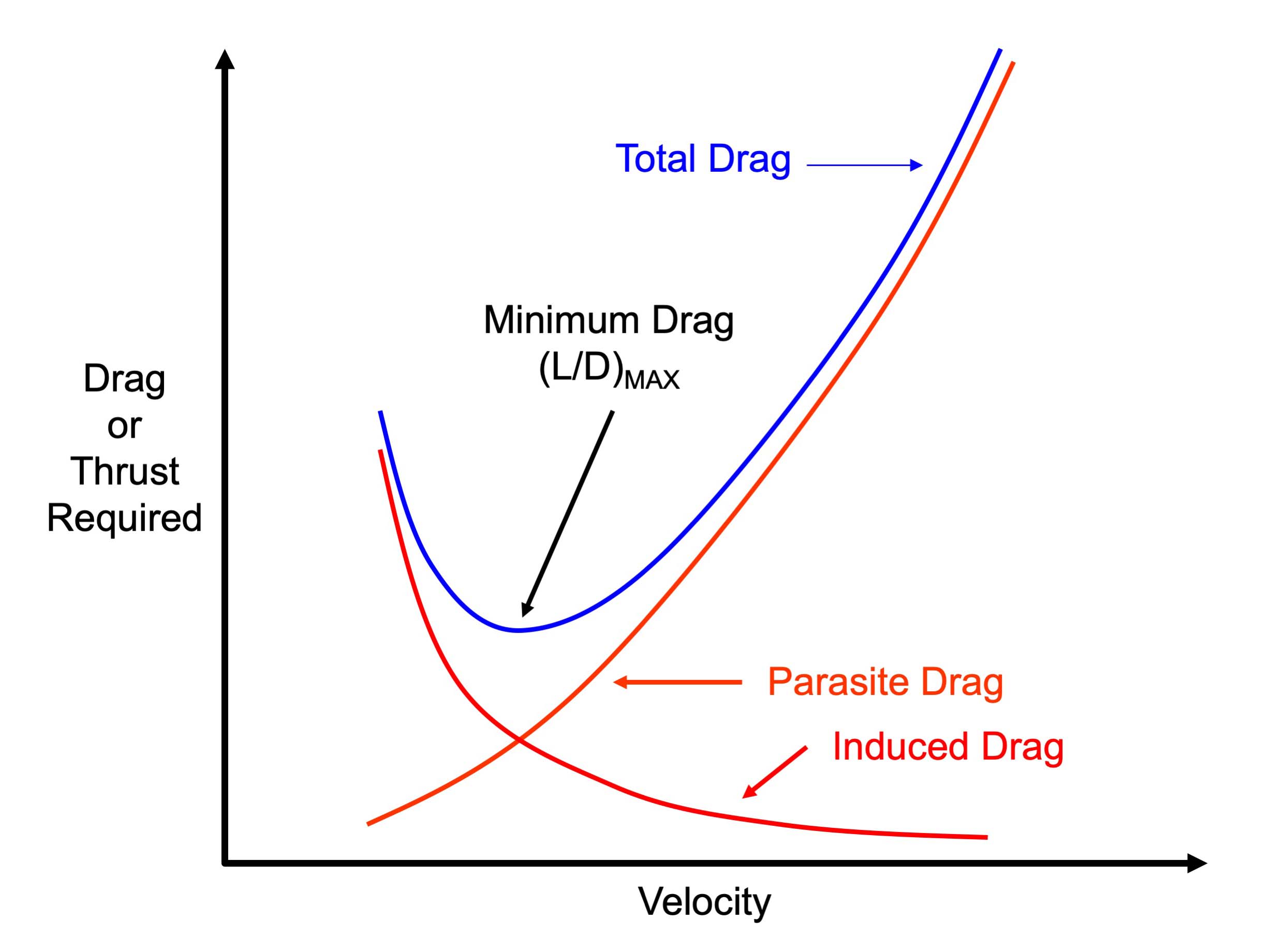

Best Glide:

- When you're trying to stretch the range of an aircraft with no engine, fly best glide airspeed.

- The closer you can nail the airspeed but if you're task saturated, +/- 5 knots should be acceptable in order to not fixate on the airspeed indicator causing other airwork or procedures to lag behind.

- Best glide is THE best glide airspeed (occurring where total drag is least).

- Pulling up the nose will cause the aircraft to shift on the drag curve toward higher induced drag.

- Lowering the nose will cause the airspeed to shift on the drag curve toward higher parasite drag.

- In both cases, the result is an increased rate of descent!

-

Selecting a Landing Area:

- It would make sense to say that we want to land on a runway or a piece of terrain that most closely mirrors.

- However, this can be challenging from the air, even more so if you're over terrain you're not familiar with, it's dark, or you're in the clouds.

- See also: BoldMethod - Your Engine Just Quit, Should You Land On A Road Or A Field?

- Be sure to tighten seat belts and shoulder harnesses as appropriate when making an emergency landing.

-

Partial Power:

- If experiencing a partial power situation, consider recent changes made, such as switching fuel tanks or mixture modifications.

- This may be due to a stuck throttle, a blocked fuel injector, or a stuck valve.

- Aircraft, if trimmed, will pitch down to compensate for loss in airspeed.

- Slow to best glide or minimum sink, depending on which is most appropriate.

- Set up for an emergency landing with the expectation that a full power loss can happen at any time.

-

Stuck Throttle:

- Throttle inputs may stick, causing the engine to be unresponsive to pilot controls.

- Throttles can stick anywhere along the range of travel, but are generally considered as high, mid, or low.

-

Stuck Throttle (High):

- Stuck throttle high occurs when the engine is stuck at a high power setting, generally relative to cruise settings.

-

Stuck Throttle (High) Primary Indications:

- Throttle remains high when lever retarded.

-

Stuck Throttle (High) Considerations:

- Consider flying to a point of intended landing and performing a power-off 180.

-

General Stuck Throttle Considerations:

- In most situations, a stuck throttle will result in a power-off landing (when cutting mixture to reduce thrust).

-

Magneto Failure:

- Magneto failures cause one of the spark plugs in a cylinder to stop firing.

- The cylinder affected will experience a higher-than-average EGT.

-

Overheating:

- Engines can overheat due to a failed cooling system or operations prohibiting effective heat management.

- In turbine engines, engines may be cooled by motoring the engine, thereby moving cool air throughout the engine.

- This may also extinguish fires due to fuel leaks.

- To better diagnose, consider that cylinders are generally numbered higher as they move from the front of the engine to the back.

- In most engines, the right side, as viewed from the cockpit, is odd-numbered, and the left is even.

- Some aircraft are different, so cylinder placement should be verified if relying on that data to make a decision.

-

Engine Fire:

- Smoke is not just smoke, color and smell matter

-

Constant-Speed Propeller Feathering:

- Loss of oil pressure will impact constant-speed propellers which utilize oil to control pitch.

- In this case, the propeller will begin, if not fully transition to its neutral setting.

- In most aircraft, this means the aircraft will feather and no longer produce thrust.

-

Propeller Overspeed:

- Loss of oil pressure may first present itself in propeller overspeed in constant-speed propellers.

- Reduce the throttle.

- Reduce pitch, as able.

-

Fuel Delivery:

- Within fuel-related accidents, fuel exhaustion and fuel starvation continue to be leading causes.

- From 2011 to 2015, an average of more than 50 accidents per year occurred due to fuel management issues.

- Fuel exhaustion accounted for 56% of fuel-related accidents while fuel starvation was responsible for 35% of these accidents.

- May be due to runing out of fuel, constrained fuel delivery via piping, or fuel injectors.

-

Fuel Delivery Primary Indications:

- Rough engine.

-

Fuel Delivery Secondary Indications:

- Dropping or low RPM.

- A "dead" cylinder if only impacting will cool quicker than others.

-

Fuel Delivery Considerations:

- If fuel delivery is not sufficient to keep the engine running smoothly, the engine may be about to quit.

- Within fuel-related accidents, fuel exhaustion and fuel starvation continue to be leading causes.

-

Hot Start:

- When the EGT exceeds the safe limit of a turbine-powered aircraft, the engine experiences a "hot start."

- Hot starts occur when too much fuel enters the combustion chamber or turbine RPM is insufficient.

- Hot starts are caused by improper starting procedures which may be cause of the pilot or electronically controlled systems.

- Any time an engine has a hot start, refer to the AFM/POH or an appropriate maintenance manual for inspection requirements.

- If the engine fails to accelerate to the proper speed after ignition or does not accelerate to idle RPM, a hung or false start has occurred.

- Reciprocating engines may be hot when start, but these procedures are deviations, and not usually cause for concern.

-

Hot Start Primary Indications:

-

Hot Start Secondary Indications:

- Engine smoke or fire.

-

Hot Start Considerations:

- Be prepared to turn off the engine.

- Note dark colored smoke is most often attributed to gas or oil while white smoke is likely electrical.

- Aging magnetos may show as the increased frequency of hot, or at least hotter, starts.

-

Hung Start:

- A hung start is typically associated with turbine engines.

- A hung start occurs when there is insufficient starting power source or fuel control malfunction.

-

Hung Start Primary Indications:

- Rising Exhaust Gas Temperatures.

-

Hung Start Secondary Indications:

- RPM does not rise.

- The engine fails to start.

-

Hung Start Considerations:

- Hung starts may be an indication of a weak or disconnecting starter.

-

Tachometer Failure:

- Tachometers can fail, be it the instrument, or connections that feed the instrument display.

- Listen to the powerplant, and determine if it is in fact the engine (see engine failure) or the instrument malfunctioning.

- The instrument is the only direct reading of RPM the pilot has, which means even if the engine sounds healthy, the engine or the tachometer are unairworthy.

- See also: First XC Solo didn't go as planned.

-

Flameout:

- A flameout occurs in the operation of a gas turbine engine in which the fire in the engine unintentionally goes out.

- If the fuel/air ratio in the combustion chamber exceeds the rich limit, the flame will blow out.

- It generally results from very fast engine acceleration, in which an overly rich mixture causes the fuel temperature to drop below the combustion temperature.

- Insufficient airflow to support combustion contribute to flameouts.

- A more common flameout occurrence is due to low fuel pressure and low engine speeds, which typically are associated with high-altitude flight.

- This situation may also occur with the engine throttled back during descent, which can set up the lean-condition flameout.

- A weak mixture can easily cause the flame to die out, even with a normal airflow through the engine.

- Any interruption of the fuel supply can result in a flameout.

- This may be due to prolonged unusual attitudes, a malfunctioning fuel control system, turbulence, icing, or running out of fuel.

- Symptoms of a flameout normally are the same as those following an engine failure.

- If the flameout is due to a transitory condition, such as an imbalance between fuel flow and engine speed, correct the situation and attempt an air-start.

- In any case, pilots must follow the applicable emergency procedures outlined in the AFM/POH.

- Generally, these procedures contain recommendations concerning altitude and airspeed where the air-start is most likely to be successful.

-

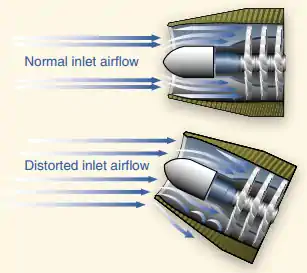

Compressor Stalls:

- Compressor blades are small airfoils and are subject to the same aerodynamic principles that apply to any airfoil.

- A compressor blade has an angle of attack, which is a result of inlet air velocity and the compressor's rotational velocity.

- These two forces combine to form a vector, which defines the airfoil's actual angle of attack to the approaching inlet air. [Figure 13]

- A compressor stall is an imbalance between the two vector quantities, inlet velocity, and compressor rotational speed.

- Compressor stalls occur when the compressor blades' angle of attack exceeds the critical angle of attack.

- At this point, smooth airflow is interrupted, creating turbulence with pressure fluctuations.

- Compressor stalls cause air flowing in the compressor to slow down and stagnate, sometimes reversing direction [Figure 6-28].

- Compressor stalls can be transient and intermittent or steady and severe.

- Indications of a transient/intermittent stall are usually an intermittent "bang" as backfire and flow reversal takes place.

- If the stall develops and becomes steady, strong vibration and a loud roar may develop from the continuous flow reversal.

- Often, the flight deck gauges do not show a mild or transient stall, but they do indicate a developed stall.

- Typical instrument indications include fluctuations in RPM and an increase in exhaust gas temperature.

- Most transient stalls are not harmful to the engine and often correct themselves after one or two pulsations.

- The possibility of severe engine damage from a steady-state stall is immediate.

- Recovery must be accomplished by quickly reducing power, decreasing the aircraft's angle of attack, and increasing airspeed.

- Although all gas turbine engines are subject to compressor stalls, most models have systems that inhibit them.

- One system uses a variable inlet guide vane (VIGV) and variable stator vanes, which direct the incoming air into the rotor blades at an appropriate angle.

- To prevent air pressure stalls, operate the aircraft within the parameters established by the manufacturer.

- If a compressor stall does develop, follow the procedures recommended in the AFM/POH.

- These occur in turbine engines using the same principles as aircraft wing stalls.

- Turbine engine compressors have an airfoil shape, and when the airflow is disturbed, it causes a stall, which creates pressure issues and leads to visible and audible stalls.

-

EGT Deviations:

- EGT deviations may be noticeable with the use of an engine monitor.

- Temperature anomalies could be the cause of an induction problem.

Aviation Fuel Anomalies & Malfunctions

-

Aviation Fuel: Fuel Imbalance:

- Fuel imbalances are covered in the controllability section below.

-

Aviation Fuel: Vapor Lock:

- Running a tank completely dry may allow air to enter the fuel system and cause vapor lock, which makes it difficult to restart the engine.

- On fuel-injected engines, the fuel becomes so hot it vaporizes in the fuel line, not allowing fuel to reach the cylinders.

-

Aviation Fuel: Loss of Fuel Pressure:

- Loss of fuel pressure can be caused by malfunctioning/failed pumps or cavitation.

-

Aviation Fuel: Fuel Leaks:

- Fuel leave severity will dictate the response required.

- Aside from running out of gas (a common accident causal factor), fuel leaks can lead to inflight fires.

Electrical Emergencies

-

Loss of Electrical Power:

- A total loss of electrical power, especially at night, can be extremely uncomfortable.

- If losing electrical power on the ground, say from discovering a dead battery during preflight, consult the maintenance manual on how to proceed.

-

Loss of Electrical Power Considerations:

- Aircraft radios will not work, requiring the use of a hand held radio.

- If at night, pilot controlled lighting will not work.

- Resist the desire to jump a dead battery, as the damage ot a low-state of charge may be irreversible.

-

Alternator Failure:

- Leading to failure, alternators may cause a whining sound to be picked up on the headset as well as generally under-perform (degraded charging).

- An alternator failure can be recognized by the batteries picking up the electrical load on the aircraft.

- The aircraft will continue to fly without the alternator, if that is the only issue.

- However, aircraft components such as radios and lights will eventually cease to function.

- This means the aircraft will not be legal to fly and may prohibit safe landing at the intended airport due to the loss of radios and transponder.

-

Alternator Failure Considerations:

- Alternator failures at night should be considered an emergency in most situations.

- Declaring emergency to buys attention and priority handling.

- How much battery time you have depends on the health and size of your battery, as well as how quickly you notice and respond to the failure.

- Turn off as much as you reasonably can.

- Glass cockpit displays are power hungry and should be load-shed to some degree.

- Consider turning off nonessential lights, especially non-LED lights, and even phone/tablet chargers.

- Pitot heat uses a lot of power, but don't turn it off if you need it.

- You can likely turn off one radio, and possibly your transponder if you're not being vectored by ATC.

- If you have an iPad you can navigate with, turn off the GPS too.

- Keep radio transmissions to a minimum-they're a significant power draw-and consider using a handheld radio proactively.

- Turn off autopilots.

- Dim the backlighting on glass displays as low as possible. If you have instruments with internal battery backups, understand how to make them switch to their internal batteries if not automatic.

- If you need more range than the battery alone will provide, you still have an option:

- Turn off the master switch and fly by iPad or dead reckoning until you're in range of an airport.

- Then turn the master back on and you'll have power to spare when you need it most.

- This is even an option in IMC on an IFR flight plan.

- Let ATC know when and where you plan to turn your radios back on, and they'll provide a frequency to call, and the controllers there will be expecting you.

- Save battery for approach phase, including instrument approaches, pilot-controlled lighting, as well as for electric flaps and landing gear.

- Tell ATC your plan and ETA before the battery dies so they can look, provide signals, and clear airspace.

- Alternator failures at night should be considered an emergency in most situations.

Pitot-Static Emergencies

- see Pitot-Static systems.

Vacuum System Emergencies

- Many aircraft run instruments off the vacuum system.

- A vacuum pump failure may cause instruments which require that negative pressure to outright fail, or worse, read inaccurately.

- Ultimately, a vacuum failure could lead to spatial disorientation.

- Vacuum pumps are usually engine-driven which means an engine failure will trigger a vacuum pump failure.

- Determining a failure requires a good instrument cross-check as the failure will likely degrade slowly.

- Instruments will not immediately flag as inoperative.

- Disable autopilots if they are designed to rely on this now inacurate information.

- Placard the instruments as able (paper, covers, etc.) and begin flying partial panel.

- Turn coordinators if electrically powered may provide (lagged) bank information.

- Under any condition, but especially in IMC, declaring an emergency allows controllers to relieve the pilot of precise instrument navigation through step-altitudes and radar vectors.

- It is recommended to divert to the nearest suitable airport.

- ATC is not responsible for the safe operation of the aircraft.

- When diverting, ensure its to a suitable airport.

Avionics Emergencies

- Making time updates on navlog will help identify the approximate location in event of an avionics failure.

- If vectored off route, the creation of internal reporting intervals will assist.

- An example would be time crossing landmarks or waypoints.

-

Attitude and Heating Reference System Familure:

- The Attitude and Heading Reference System, or AHRS, interprets and displays pitch, bank, and heading information to the avionics, the failure of which will display erroneous or inaccurate data.

- Depending on installation, there may be redunant systems which to rely on.

- Due to variance between systems, pilots must become familiar with the specific system they operate.

- Failure of certain data should reflect as a red "X" on that information.

-

Display System Failure:

- Glass cockpit displays, sometimes called Primary Flight or Multi-Function Flight Displays (PFDs/MFDs) display information from AHRS to the pilot.

- Often, two screens are installed providing a primary and backup display, with the same information displayable on both.

- Pilots should consider practicing (with supervision) flying with the primary display on the other side of the aircraft in the event of a display system failure.

Oil/Lubrication Malunfctions/Emergencies

- Oil consumption depends primarily upon the efficiency of the seals.

- Oil can be lost through internal leakage, and, in some engines, by malfunctioning of the pressurizing or venting system.

- Increases in oil temperature are not always associated with a drop in oil pressure, nor a rise in CHTs.

-

Low Oil Pressure:

- Low oil pressure can be caused by an oil leak which leads to lack of oil in the system, or an ineffective oil pump.

- These emergencies can be particularly detrimental when flying an aircraft utilizing a constant-speed propeller.

-

Low Oil Pressure Primary Indications:

- Oil pressure will indicate low.

-

Low Oil Pressure Secondary Indications:

- Rising Cylinder Head Temperatures (CHT).

- Oil temperature may rise (if the pressure drops rapidly then it is less likely you will have a corresponding temperature indication.

- Rough engine indications.

-

Low Oil Temperature:

Primary Indications:

- Oil temperature will indicate low.

Secondary Indications:

-

High Oil Temperature:

-

High Oil Temperature Primary Indications:

- Oil temperature will indicate high.

-

High Oil Temperature Secondary Indications:

- Other temperatures will indicate high.

- Possible smoke.

- Low oil pressure.

- High RPM.

-

High Oil Temperature Considerations:

- Open cowl flaps, if equipped.

-

-

Oil Leaks:

- Ensure dipsticks are properly secured (not cross-threaded) to prevent leaks.

- Oil on windscreen may come from engine or propeller.

- Oil leaks will smoke when in contact with hot engine components.

VMC into IMC

- VMC into IMC, also called inadvertant IMC, remains a killer for pilots.

- These conditions can creep up on pilots in areas with fast moving weather/storm development and especially at night.

- In a 1954 study conducted by the University of Illinois, it was found that pilots under a particular VMC into IMC scenario had on average 178 seconds before they would become disoriented and lose control after entering IMC and attempting a 180 degree turn out.

- This study demonstrates the importance for instrument instruction and occasional proficiency to handle such situations.

- If entering IMC, relax and realize your quickest way out is almost certainly a 180 degree turn.

- When executing a 180 degree turn, perform a standard rate or even slower rate/lower bank angle turn.

- Pilots can get into trouble by trying to speed up the turn and using an overly aggressive bank angle, resulting in lost altitudes, pitch adjustments, etc. - simplify the problem as much as possible.

- Ask for help from ATC if needed.

- See also AOPA's VFR into IMC Avoidance and Escape resources.

Aircraft Fires

- Consider, if the operating handbook does not already call for it, bringing the mixture to idle cut-off, and moving the fuel selector to OFF to remove a fuel source from the fire.

- Smoke is not just smoke, color and smell matter.

- When exiting the aircraft, always exit to the upwind direction as smoke and fumes are toxic.

- Expect smoke and fumes may result in tearing of the eyes, impairing vision.

- Aircraft fires on start up (called stack fires) can occur with a flooded engine.

- Consider always wearing flame resistent clothing or cotton when flying, but never synthetics as they can melt to skin.

- If smoke comes from the engine cowling, if winds permit, consider slipping in such a way to be able to see.

- If employing a fire extinguisher, be prepared to hold breath for a period of time as toxic fumes (displacing oxygen) will fill the cabin and need time to dissipate.

- The time from the start of a fire to significant damage such as melting or comrpomised components can be less than 1 minute.

- Landing immediately!

Controllability

-

Flight Control Jam:

- Once identified, use other control surfaces to overcome the forces.

- Consider the use of trim to increase effects while minimize control pressures.

- If necessary, but unable, to lower the nose to prevent an unsafe condition (i.e., a stall), rolling the aircraft into an angle of bank will cause the nose to drop.

-

Controllability: Fuel Imbalance:

- Many aircraft are equipped with a fuel selector which allows you to select which tank, or both, from which to draw fuel

- Aircraft can at times develop a fuel imbalance from various sources:

- Prolonged turns in the same direction

- Mechanical reasons

- Improper monitoring of the fuel selector valve.

- If a fuel imbalance occurs, select the appropriate (fullest tank) to even out the fuel levels

-

Flap Asymmetry:

- An asymmetric "split" flap situation is one in which one flap deploys or retracts while the other remains in position.

- A split-flap condition is not to be confused with split-flap designs.

- Split-flap conditions can result in a dramatic rolling moment toward the least deflected flap.

- Pilots can counter any rolling moments with opposite aileron.

- Opposite rudder will be required to overcome the adverse yaw caused by the additional drag on the wing with the extended flap.

- The aircraft is now in a cross-controlled situation.

- To solve this problem, the pilot may attempt to raise the flaps again.

- Weigh the cost of retracting the flaps, which could fix the situation or could cause more damage.

- Consider flying faster approaches.

- With one wing that does not have flaps, it will stall earlier, requiring a higher-than-normal approach speed.

- Pilots may need up to full aileron deflection to maintain a wings-level attitude, especially at the reduced airspeed necessary for approach and landing.

- The pilot should not risk an asymmetric stall and subsequent loss of control by flaring excessively.

- Rather, the airplane should be flown onto the runway so that the touchdown occurs at an airspeed consistent with a safe margin above flaps-up stall speed.

- The pilot should not attempt to land with a crosswind from the side of the deployed flap because the additional roll control required to counteract the crosswind may not be available.

- Some aircraft designs include physically interconnected flaps to prevent flap asymmetry.

- Pilots may choose not to extend flaps in a turn to avoid risks associated with an asymmetric flap situation while already in a turn.

- An asymmetric "split" flap situation is one in which one flap deploys or retracts while the other remains in position.

-

Flap Actuation Failure:

- If the flap fails to respond to an input (i.e., extension commanded, no extension occurs) then consider leaving the flap lever in the position to the corresponding flap position.

- If the flap actuator suddenly works, you don't want a surprise like full flap extension or retraction.

- If the flap fails to respond to an input (i.e., extension commanded, no extension occurs) then consider leaving the flap lever in the position to the corresponding flap position.

-

Runaway Trim:

- Runaway trim is a condition in which an electric trim motor has become stuck, causing the trim to move when uncommanded.

- Runaway trim can result in a serious flight control problem where the pilot has to muscle the controls to try and maintain a flyable aircraft.

- To solve this problem, the pilot should pull the circuit breaker for the trim motor.

- Not having an understanding or knowing where to reference the circuit breaker diagram quickly can make this easy task difficult.

-

Opened Door:

- An opened door is not an emergency until the pilot tries to take an action and loses control of the aircraft.

- The amount of airflow over the fuselage makes opening the door to slam it shut difficult, tempting the slowing of airspeed closer to stall speed.

- The performance impacts of a door opening in flight are minimal.

- It is always best to simply land, shut the door, and take off again.

-

Controllability Test:

- Consider a controllability test if time and altitude permit when aircraft control has been called into question before attempting a recovery.

- Consider the impacts of not only control surfaces, but configuration and throttle settings.

- High throttle settings can help pitch aircraft up, or reduce descent.

Landing Gear-Related Emergencies

-

Landing Gear Fails to Retract:

- When the landing gear will not retract after takeoff, the pilot should leave the landing gear extended.

- Trying to force the landing gear to retract may cause the landing gear to become stuck in the retracted position.

- Landing gear position may be confirmed by the tower, or other aircraft.

- If the landing gear appears locked down then flight may be continued at reduced performance.

- Consideration should be given to rescue services at the destination in the event of further emergency.

- Consideration should be given to inspecting the landing gear prior to taxi following landing.

- When the landing gear will not retract after takeoff, the pilot should leave the landing gear extended.

-

Landing Gear Fails to Extend:

- When the landing gear will not extend, the pilot should first find a safe location at a safe altitude to troubleshoot.

- Try to manually extend the landing gear.

- If a gear up landing is required, consideration should be given to pavement vs. grass, to ensure a smoother landing (no bumps, etc.

- Consideration should also be given to fields with the appropriate services desired after an emergency landing.

- Landing gear position may be confirmed by the tower, or other aircraft.

- Even if tower confirms gear appears down, it may not be locked.

- Consider requesting the runway to be foamed to avoid a fire upon landing, as available.

-

Parking Brake Fails to Disengage:

- If the parking brake fails to disengage in a tricycle gear aircraft, more than likely the aircraft won't move or it will try to rotate about the stuck wheel.

- The risk to the aircraft is relatively minimal, of course unless their are objects very near by.

- Tail dragger airplanes risk a prop strike if attempted to move, as the aircraft will immediately rotate forward.

- If the parking brake fails to disengage in a tricycle gear aircraft, more than likely the aircraft won't move or it will try to rotate about the stuck wheel.

-

Shimmy Damper Failure:

- Dampener shimmy will be felt in rudder pedals when malfunctioning.

Emergency Autoland

Night Considerations

- If lased, consider turning off aircraft lights to mask position from future incidents in that area, but notify ATC.

Distress Procedures

- Do not hesitate to declare an emergency if in distress.

- An aircraft in an urgency condition needs to recognize when a situation becomes that of distress.

- Safety is not a luxury! Take action.

- Distress frequencies, procedures, signals, and call signs may be assigned.

- A copy of the applicable procedures and signals shall be carried in the cockpit of all naval aircraft and may be used in time of peace regardless of the degree of radio silence that may be imposed during tactical exercises.

- They will be used in time of war when prescribed by the officer in tactical command and may be amplified as necessary to cover local conditions or specific military operations.

Aircraft Rescue & Fire Fighting Communications (ARFF)

-

Discrete Emergency Frequency:

- Direct contact between an emergency aircraft flight crew, Aircraft Rescue and Fire Fighting Incident Commander (ARFF IC), and the Airport Traffic Control Tower (ATCT), is possible on an aeronautical radio frequency (Discrete Emergency Frequency [DEF]), designated by Air Traffic Control (ATC) from the operational frequencies assigned to that facility.

- Emergency aircraft at airports without an ATCT, (or when the ATCT is closed), may contact the ARFF IC (if ARFF service is provided), on the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) published for the airport or the civil emergency frequency 121.5 MHz.

-

Radio Call Signs:

- Preferred radio call sign for the ARFF IC is "(location/facility) Command" when communicating with the flight crew and the FAA ATCT.

- Example: LAX Command.

- Example: Washington Command.

- Preferred radio call sign for the ARFF IC is "(location/facility) Command" when communicating with the flight crew and the FAA ATCT.

-

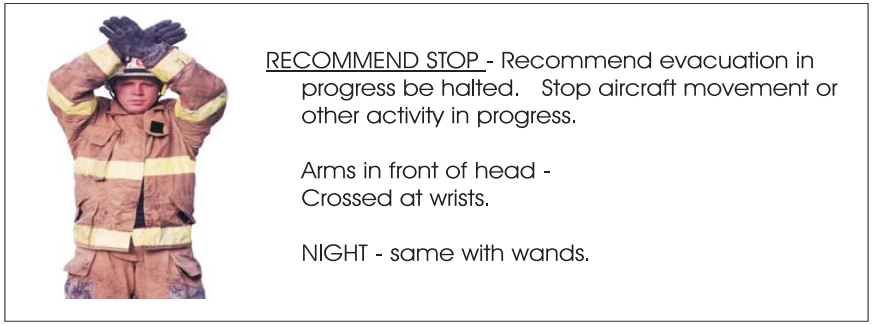

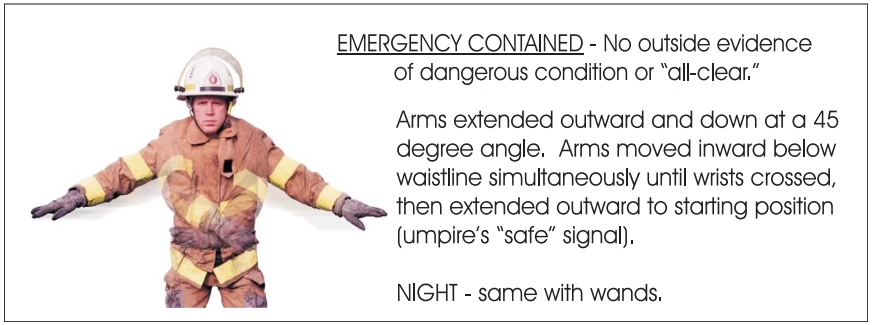

ARFF Emergency Hand Signals:

- In the event that electronic communications cannot be maintained between the ARFF IC and the flight crew, standard emergency hand signals as depicted below should be used.

- These hand signals should be known and understood by all cockpit and cabin aircrew, and all ARFF firefighters.

Definitions

WARNING:

- An operating procedure, practice, or condition, etc., that may result in injury or death if not carefully observed or followed.

CAUTION:

- An operating procedure, practice, or condition, etc., that may result in damage to equipment if not carefully observed or followed.

NOTE:

- An operating procedure, practice, or condition, etc., that is essential to emphasize.

Shall:

- Mandatory.

Should:

- Recommended.

May:

- Optional.

Will

- Indicates futurity, never indicates any degree of requirement for application of a procedure.

Formation Emergencies

- The emergency aircraft has the lead unless they don't want it, "bleeder is the leader."

- In NORDO situations, any HEFOE from the emergency aircraft means lead brings you back for a HALF flap, straight-in approach.

- Be ready with the book to assist a wingman.

Conclusion

- Always Aviate, Navigate and Communicate.

- Two things will kill you immediately: hitting the ground or another airplane.

- Think first before you act, and avoid a startle response.

- The pilot in command, has the final authority in the operation of the aircraft.

- It is okay to say "unable" to ATC if in your mind it will put the aircraft into a dangerous state.

- Still, ATC can declare an emergency on your behalf, which does not give them authority over you, but does raise your priority/level of service.

- Don't allow a lack of instrument charts to rule out an airport.

- ATC can provide all the information necessary to land.

- Pay attention to those procedures requiring immediate attention and, therefore, must be memorized.

- If a step ties directly to an immediate safety concern, the step should be memorized.

- If equipped with an autopilot, consider flying the aircraft by hand in any emergency.

- While the use of an autopilot to reduce task saturation is tempting, flying by hand maintains tactile feedback on aircraft performance.

- In the event of a pilot incapacitation, an Emergency Autoland system or an emergency descent system may assume operation of the aircraft and deviate to meet that emergency.

- In several cases, an inflight malfunction requires immediate notification to the NTSB.

- Still looking for something? Continue searching:

References

- Aeronautical Information Manual (4-1-17) Radar Assistance to VFR Aircraft

- Aeronautical Information Manual (6-1-1) Pilot Responsibility and Authority

- Aeronautical Information Manual (6-1-2) Emergency Condition - Request Assistance Immediately

- Aeronautical Information Manual (6-3-2) Obtaining Emergency Assistance

- Aeronautical Information Manual (6-5-1) Discrete Emergency Frequency

- Aeronautical Information Manual (6-5-1) Radio Call Signs

- Aeronautical Information Manual (6-5-1) ARFF Emergency Hand Signals

- Aeronautical Information Manual (7-5-1) Emergency Procedures

- AOPA - Emergency Procedures Resources

- Bold Method - Asymmetric Flap Failure? Here's How To Land Safely

- Bold Method - What Can You Do If You Lose Elevator Control In Flight?

- Bold Method - Rudder Failure On Takeoff... What Would You Do?

- Bold Method - Your Elevator Trim Just Jammed. What Should You Do?

- Bold Method - Propeller Overspeed

- Bold Method - Your Throttle Is Stuck At Full Power. What Would You Do?

- Federal Aviation Administration - Pilot/Controller Glossary

- FAA - 178 Seconds to Live

- Federal Aviation Administration - Nuisance Alerts in Operational ATC Environments: Classification and Frequencies

- Bold Method - 10 Times It's Appropriate To Say 'Unable' To ATC

- Bold Method - Your Engine Just Quit, Should You Land On A Road Or A Field?

- Bold Method - Handling a Split Flap Emergency

- Pilot Workshops - Can a VFR Pilot Survive in IMC?

- Federal Aviation Administration Safety Briefing - Best Glide Speed and Distance

- FAA Safety Alert (067) Flying on Empty

- Federal Aviation Regulations (91.3) Responsibility and authority of the pilot in command

- Federal Aviation Regulations (91.185)

- AOPA - Engine failure during flight?

- FAA Safety Team - Emergency Procedures Training

- Aircraft Maintenance: Pitot-Static System Failures

- FAA - Emergency Procedures Training

- Pilot Workshop - Emergency Checklist

- Pilot Workshop - Engine Failure: #1 Rule