Atmosphere

The atmosphere is the envelope of air that governs the properties and conditions whereby aircraft operate.

Introduction to the Atmosphere

- The atmosphere, simply put, is the envelope of air which surrounds the Earth

- The standard atmosphere was defined to provide a common denominator for atmospheric values

- This enables us to work from average values of temperature, pressure, and density as it relates to us (altitude above mean sea level)

- Weather is caused from the sun and unequal heating of the Earth's surface

- In fact weather is a direct result from the Earth spinning

- If the Earth were to stop rotating, there would be no weather

- Unequal heating creates a temperature imbalance between the poles

Atmosphere

- The Earth's atmosphere is a cloud of gas and suspended solids extending from the surface out many thousands of miles, becoming increasingly thinner with distance

- It is as much a part of the Earth as the seas or the land, but air differs from land and water as it is a mixture of gases

- It has mass, weight, and indefinite shape which are in motion

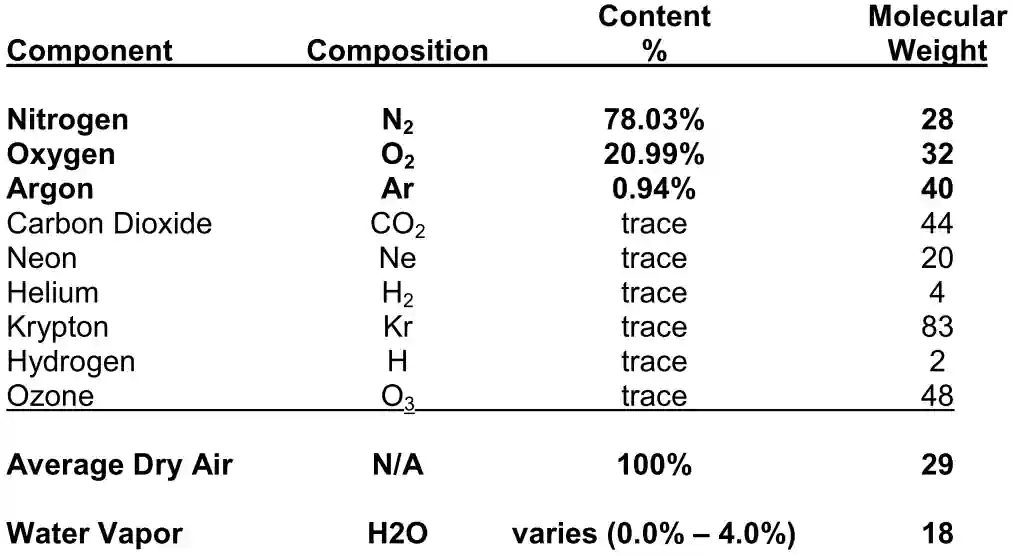

- The atmosphere is composed of 78 percent nitrogen, 21 percent oxygen, and 1 percent other gases, such as argon or helium [Figure 1]

- The heavier elements, such as oxygen, settle to the surface of the Earth, while the lighter elements are lifted up to the region of higher altitude

- The percentage of these gases remain relatively constant throughout all levels of the atmosphere

- The "sink" of heavier elements however, contributes to pressure

-

Air Parcel:

- An air parcel is an imaginary volume of air to which any or all of the basic properties of atmospheric air may be assigned

- A parcel is large enough to contain a very large number of molecules, but small enough so that the properties assigned to it are approximately uniform

- In meteorology, an air parcel is used as a tool to describe certain atmospheric processes, and we will refer to air parcels throughout this document

-

Standard Atmosphere:

- To create a fixed standard for reference, the standard atmosphere was created as a hypothetical vertical distribution of atmospheric temperature, pressure, and density that, by international agreement, is taken to be representative of the atmosphere for purposes of pressure altimeter calibrations, aircraft performance calculations, aircraft and missile design, ballistic tables, etc.

Atmospheric Structure

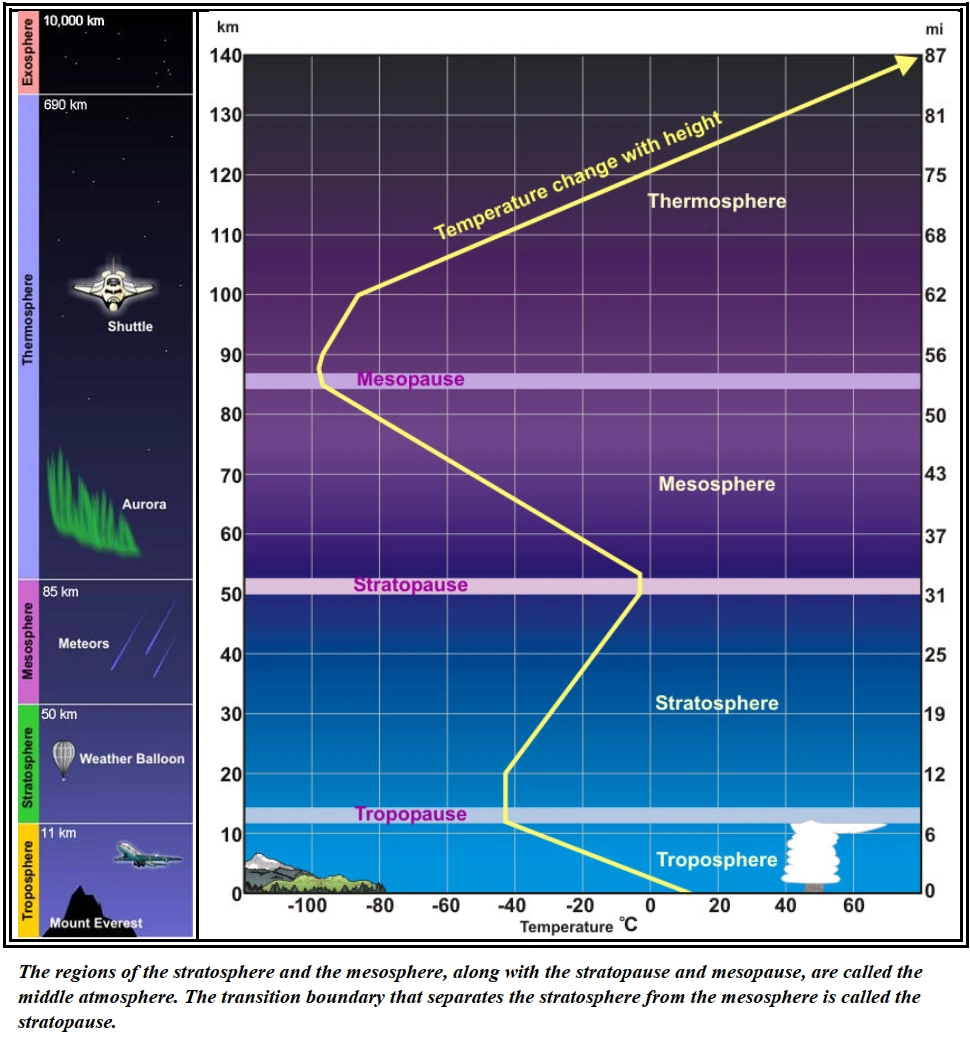

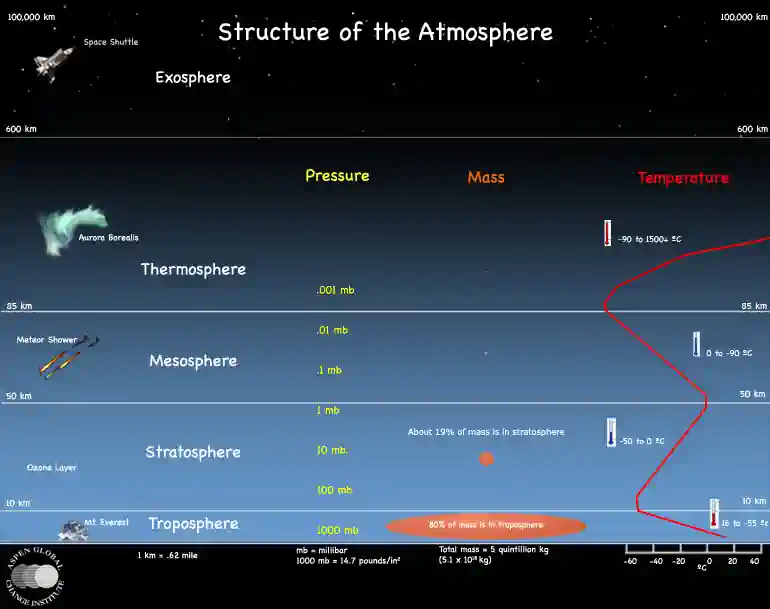

- Temperatures, chemical composition, movement, and density differences divide the atmosphere into five district atmospheric layers

- Troposphere

- Stratosphere

- Mesosphere

- Thermosphere

- Exosphere

- Each of the five layers is topped by a pause, where the maximum changes in thermal characteristics, chemical composition, movement, and density occur

-

Troposphere:

- The trophosphere starts at the Earth's surface and extends approximately 36,000'

- The vertical depth of the troposphere varies due to temperature variations which are closely associated with latitude and season

- It decreases from the Equator to the poles, and is higher during summer than in winter

- The transition boundary between the troposphere and the layer above is called the tropopause

-

Stratosphere:

- The stratosphere starts just above the troposphere and extends to approximately 160,000'

- This layer holds about 19 percent of the atmosphere's gases, but very little water vapor

- The transition boundary between the stratosphere and the layer above is called the stratopopause

-

Mesophere:

- The mesosphere starts just above the stratosphere and extends to 280,000' (53 mi)

- The transition boundary between the mesosphere and the layer above is called the mesopopause

-

Thermosphere:

- The thermosphere starts just above the mesosphere and extends to 1,848,000 ft (350 mi)

- The transition boundary between the thermosphere and the layer above is called the thermopopause

-

Exosphere:

- The exosphere is the outermost layer of the atmosphere

Atmospheric Pressure

- Although there are various kinds of pressure, pilots are mainly concerned with atmospheric pressure

- It is one of the basic factors in weather changes, helps to lift an aircraft, and actuates some of the important flight instruments

- These instruments are the altimeter, airspeed indicator, vertical speed indicator, and manifold pressure gauge

- Air is very light, but it has mass and is affected by the attraction of gravity

- Therefore, like any other substance, it has weight, and because of its weight, it has force

- Since air is a fluid substance, this force is exerted equally in all directions

- Its effect on bodies within the air is called pressure

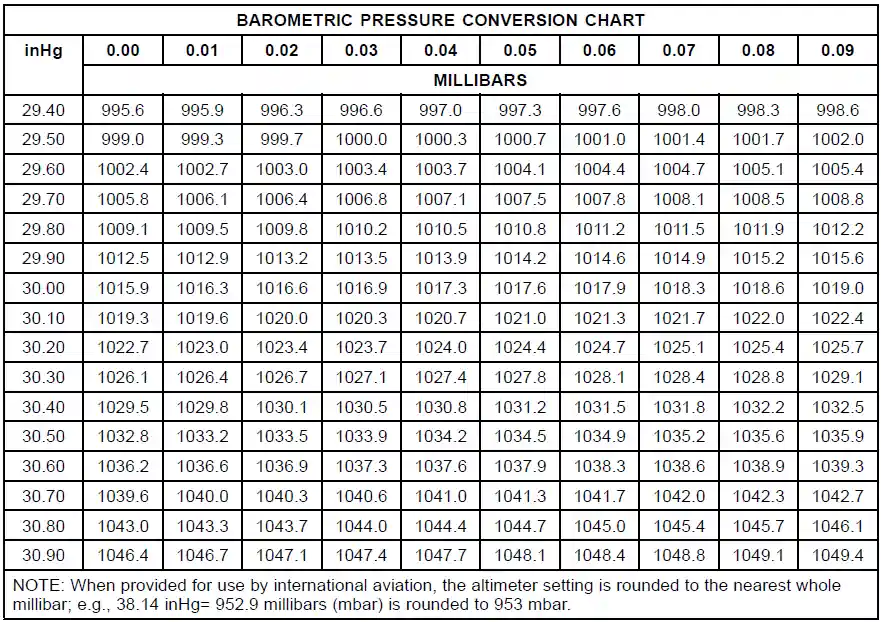

- Under standard conditions at sea level, the average pressure exerted by the weight of the atmosphere is approximately 14.70 pounds per square inch (psi) of surface, or 1,013.2 millibars (mb)

- The thickness of the atmosphere is limited; therefore, the higher the altitude, the less air there is above

- For this reason, the weight of the atmosphere at 18,000 feet is one-half what it is at sea level

- The pressure of the atmosphere varies with time and location

- Due to the changing atmospheric pressure, a standard reference was developed

- The standard atmosphere at sea level is a surface temperature of 59 °F or 15 °C and a surface pressure of 29.92 inches of mercury ("Hg) or 1,013.2 mb

-

Lapse Rates:

- A lapse rate is the rate at which air temperature or pressures change with changes in altitude

- There are generally two ways we refer to lapse rates, temperature, and pressure

-

Temperature Lapse Rate:

- A standard temperature lapse rate (in the troposphere) is when the temperature decreases, on average, at the rate of approximately 3.5 °F or 2 °C per thousand feet up to 36,000 feet, which is approximately –65 °F or –55 7deg;C

- Lapse rate is affected by moisture content of the air

- The dry lapse rate is 3°C per 1,000'

- The moist lapse rate is between 1.1 and 2.8°C per 1,000'

- Lapse rate is affected by moisture content of the air

- In the stratosphere, temperature is constant (isothermal at -70°F (-57°C)

- Any temperature that differs from the standard lapse rates is considered nonstandard temperature

-

Temperature Inversions:

- Typically, temperatures decrease with altitude

- However, a temperature inversion is a condition where temperature increases (vice the standard decrease) with altitude (A layer of cold air lies under a layer of warmer air)

- It can be visually recognized by trapped smoke or moisture layers

- May occur when ground cools faster than air aloft, aided by high pressure systems on clear nights

- Inverstions mostly occur in mornings/evenings

- Valleys are prime locations for inversions and assocaited fog as cold air sinks into warm air

- Capping inversions can occur when cold fronts push warm air ahead of it upward

- A standard temperature lapse rate (in the troposphere) is when the temperature decreases, on average, at the rate of approximately 3.5 °F or 2 °C per thousand feet up to 36,000 feet, which is approximately –65 °F or –55 7deg;C

-

Pressure Lapse Rate:

- A standard pressure lapse rate (in the troposphere) is when pressure decreases at a rate of approximately 1 "Hg per 1,000 feet of altitude gain to 10,000 feet

- Above the troposphere, pressure begins to decrease faster (less air above to "push" the other air down)

- Note that standard lapse rates are for a "standard atmosphere

- The real atmosphere will contain inversions and higher or lower lapse rates

- Additionally, seasonal effects will raise or lower the start of the isothermal stratosphere

- The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has established this as a worldwide standard, and it is often referred to as International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) or ICAO Standard Atmosphere

- Any pressure that differs from the standard lapse rates is considered nonstandard pressure

- Since aircraft performance is compared and evaluated with respect to the standard atmosphere, all aircraft instruments are calibrated for the standard atmosphere

-

Pressure and Density Altitudes:

- There are two measurements of the atmosphere that affect performance and instrument calibrations: pressure altitude and density altitude

-

Pressure Altitude:

- Pressure altitude is the height above a standard datum plane (SDP), which is a theoretical level where the weight of the atmosphere is 29.92 "Hg (1,013.2 mb) as measured by a barometer (and the weight of the air is 14.7 PSI).

- An altimeter is essentially a sensitive barometer calibrated to indicate altitude in the standard atmosphere

- If the altimeter is set for 29.92 "Hg SDP, the altitude indicated is the pressure altitude

- As atmospheric pressure changes, the SDP may be below, at, or above sea level

- Pressure altitude is important as a basis for determining airplane performance, as well as for assigning flight levels to airplanes operating at or above 18,000 feet

- The pressure altitude can be determined by:

- Setting the barometric scale of the altimeter to 29.92 and reading the indicated altitude, or;

- Applying a correction factor to the indicated altitude according to the reported altimeter setting

- Pressure altitude is the height above a standard datum plane (SDP), which is a theoretical level where the weight of the atmosphere is 29.92 "Hg (1,013.2 mb) as measured by a barometer (and the weight of the air is 14.7 PSI).

-

Density Altitude:

- SDP is a theoretical pressure altitude, but aircraft operate in a nonstandard atmosphere and the term density altitude is used for correlating aerodynamic performance in the nonstandard atmosphere. Density altitude is the vertical distance above sea level in the standard atmosphere at which a given density is to be found. The density of air has significant effects on the aircraft's performance because as air becomes less dense, it reduces:

- Power because the engine takes in less air

- Thrust because a propeller is less efficient in thin air

- Lift because the thin air exerts less force on the airfoils

- Density altitude is pressure altitude corrected for nonstandard temperatures, and is used for determining aerodynamic performance in the nonstandard atmosphere

- Density altitude increases with increases in temperature and moisture content of the air, and a decrease in pressure (altitude).

- As the density of the air increases (lower density altitude), aircraft performance increases; conversely as air density decreases (higher density altitude), aircraft performance decreases

- A decrease in air density means a high density altitude; an increase in air density means a lower density altitude

- Density altitude is used in calculating aircraft performance because under standard atmospheric conditions, air at each level in the atmosphere not only has a specific density, its pressure altitude and density altitude identify the same level

- The computation of density altitude involves consideration of pressure (pressure altitude) and temperature. Since aircraft performance data at any level is based upon air density under standard day conditions, such performance data apply to air density levels that may not be identical with altimeter indications. Under conditions higher or lower than standard, these levels cannot be determined directly from the altimeter

- Density altitude is determined by first finding pressure altitude, and then correcting this altitude for nonstandard temperature variations. Since density varies directly with pressure and inversely with temperature, a given pressure altitude may exist for a wide range of temperatures by allowing the density to vary. However, a known density occurs for any one temperature and pressure altitude. The density of the air has a pronounced effect on aircraft and engine performance. Regardless of the actual altitude of the aircraft, it will perform as though it were operating at an altitude equal to the existing density altitude

- Air density is affected by changes in altitude, temperature, and humidity. High density altitude refers to thin air, while low density altitude refers to dense air. The conditions that result in a high density altitude are high elevations, low atmospheric pressures, high temperatures, high humidity, or some combination of these factors. Lower elevations, high atmospheric pressure, low temperatures, and low humidity are more indicative of low density altitude

-

Effect of Pressure on Density:

- Since air is a gas, it can be compressed or expanded. When air is compressed, a greater amount of air can occupy a given volume. Conversely, when pressure on a given volume of air is decreased, the air expands and occupies a greater space. At a lower pressure, the original column of air contains a smaller mass of air. The density is decreased because density is directly proportional to pressure. If the pressure is doubled, the density is doubled; if the pressure is lowered, the density is lowered. This statement is true only at a constant temperature

-

Effect of Temperature on Density:

- Increasing the temperature of a substance decreases its density

- Conversely, decreasing the temperature increases the density

- Thus, the density of air varies inversely with temperature

- This statement is true only at a constant pressure

- In the atmosphere, both temperature and pressure decrease with altitude and have conflicting effects upon density

- However, a fairly rapid drop in pressure as altitude increases usually has a dominating effect

- Hence, pilots can expect the density to decrease with altitude

- Increasing the temperature of a substance decreases its density

-

Density Altitude Calculation Example:

- If a chart is not available the density altitude can be estimated by adding 120' for every degree Celsius above the ISA:

- Pressure Altitude = 600' (as calculated above)

- OAT: 10°C

- ISA Temp (using standard Lapse rate of -2 degrees C per 1000 ft) is 14° C

- 600' + [120 * (10-14)]

- 600' + (-480) = 120'

-

Effect of Humidity (Moisture) on Density:

- Since air is never completely dry, a small amount of water vapor is always present in the atmosphere

- In other conditions humidity may become an important factor in the performance of an aircraft

- Water vapor is lighter than air; consequently, moist air is lighter than dry air

- Therefore, as the water content of the air increases, the air becomes less dense, increasing density altitude and decreasing performance

- It is lightest or least dense when, in a given set of conditions, it contains the maximum amount of water vapor

- Humidity, also called relative humidity, refers to the amount of water vapor contained in the atmosphere and is expressed as a percentage of the maximum amount of water vapor the air can hold

- This amount varies with temperature (Warm air holds more water vapor, while cold air holds less

- Perfectly dry air that contains no water vapor has a relative humidity of zero percent, while saturated air, which cannot hold any more water vapor, has a relative humidity of 100 percent

- Humidity alone is usually not considered an important factor in calculating density altitude and aircraft performance, but it is a contributing factor

- As temperature increases, the air can hold greater amounts of water vapor

- When comparing two separate air masses, the first warm and moist (both qualities tending to lighten the air) and the second cold and dry (both qualities making it heavier), the first must be less dense than the second

- Pressure, temperature, and humidity have a great influence on aircraft performance because of their effect upon density

- There are no rules of thumb that can be easily applied, but the affect of humidity can be determined using several online formulas

- As an example, the pressure is needed at the altitude for which density altitude is being sought

- Using [Figure 2], select the barometric pressure closest to the associated altitude

- The standard pressure at 8,000 feet is 22.22 "Hg

- Using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) website (www.srh.noaa.gov/ epz/?n=wxcalc_densityaltitude) for density altitude, enter the 22.22 for 8,000 feet in the station pressure window

- Enter a temperature of 80° and a dew point of 75°

- The result is a density altitude of 11,564 feet

- With no humidity, the density altitude would be almost 500 feet lower

- Another website (www.wahiduddin.net/calc/density_altitude.htm) provides a more straight forward method of determining the effects of humidity on density altitude without using additional interpretive charts

- In any case, the effects of humidity on density altitude include a decrease in overall performance in high humidity conditions

- Learn more here

-

Effects of Density Altitude on True Airspeed:

- True airspeed increases (decreases) as outside air temperature increases (decreases).

-

Effects of Density Altitude on True Airspeed:

- Increased temperature also increases density altitude.

- When density altitude increases (decreases), the airplane must be flown faster (slower) to maintain the same pressure differential between pitot impact pressure and static pressure.

- Therefore, for a given CAS, TAS increases as altitude increases.

- Conversely, or for a given TAS, CAS decreases as altitude increases.

- Increased temperature also increases density altitude.

-

Effects of Temperature on True Altitude:

- True altitude increases (decreases) as outside air temperature increases (decreases).

- Think "low-to-high, clear the skies" or "high-to-low, looking below.

- Increased temperature also increases density altitude.

- SDP is a theoretical pressure altitude, but aircraft operate in a nonstandard atmosphere and the term density altitude is used for correlating aerodynamic performance in the nonstandard atmosphere. Density altitude is the vertical distance above sea level in the standard atmosphere at which a given density is to be found. The density of air has significant effects on the aircraft's performance because as air becomes less dense, it reduces:

-

Density Altitude Advisories:

- At airports with elevations of 2,000' and higher, control towers and FSSs will broadcast the advisory "Check Density Altitude" when the temperature reaches a predetermined level

- These advisories will be broadcast on appropriate tower frequencies or, where available, ATIS

- FSSs will broadcast these advisories as a part of Local Airport Advisory

- These advisories are provided by air traffic facilities, as a reminder to pilots that high temperatures and high field elevations will cause significant changes in aircraft characteristics

- The pilot retains the responsibility to compute density altitude, when appropriate, as a part of preflight duties

- All FSSs will compute the current density altitude upon request

International Standard Atmosphere (ISA)

- The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) established the ICAO Standard Atmosphere as a way of creating an international standard for reference and performance computations

- Instrument indications and aircraft performance specifications are derived using this standard as a reference

- Because the standard atmosphere is a derived set of conditions that rarely exist in reality, pilots need to understand how deviations from the standard affect both instrument indications and aircraft performance

- In the standard atmosphere, sea level pressure is 29.92" inches of mercury (Hg) and the temperature is 15° C (59° F)

- The standard lapse rate for pressure is approximately a 1" Hg decrease per 1,000' increase in altitude

- The standard lapse rate for temperature is a 2° C (3.6° F) decrease per 1,000' increase, up to the top of the stratosphere

- Since all aircraft performance is compared and evaluated in the environment of the standard atmosphere, all aircraft performance instrumentation is calibrated for the standard atmosphere

- Because the actual operating conditions rarely, if ever, fit the standard atmosphere, certain corrections must apply to the instrumentation and aircraft performance

- For instance, at 10,000 ISA predicts that the air pressure should be 19.92" Hg (29.92" - 10" Hg = 19.92") and the outside temperature at -5°C (15° C - 20° C)

- If the temperature or the pressure is different than the International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) prediction an adjustment must be made to performance predictions and various instrument indications

Temperature

- Temperature is the degree of heat present in a substance or object.

- The atmosphere (air) varies in temperature and is measured in degrees Celsius and Fahrenheit.

- Celsius is the standard aviation unit for temperature.

- The standard atmospheric temperature is 15°C or 59°F.

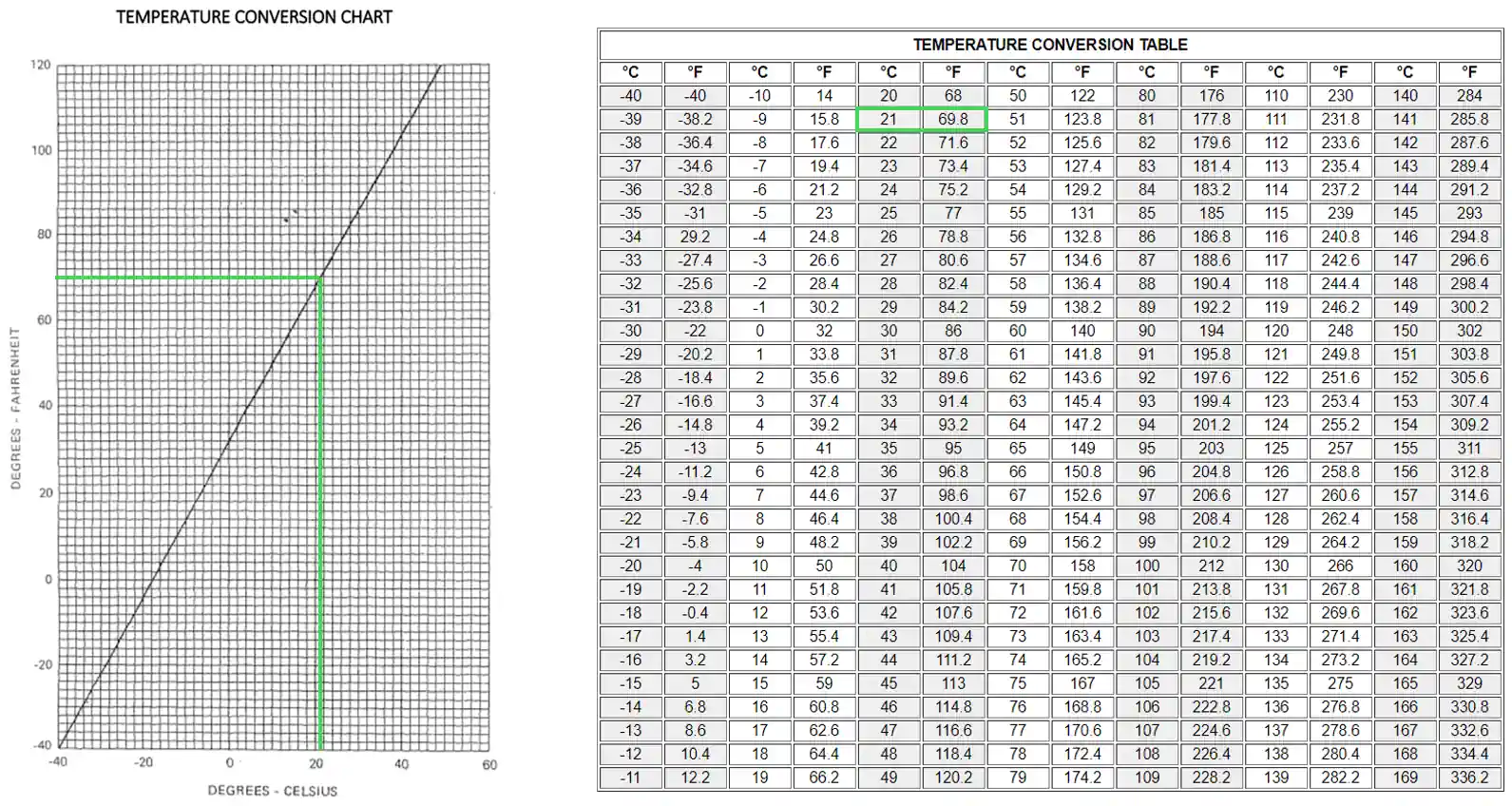

- Pilots convert between °F and °C using formulas, charts, or tables. [Figure 1]

-

Temperature Conversion Formula:

- °C = [(°F - 32) x 5/9].

- °F = [(°C x 9/5) + 32].

-

Temperature Calculation Example:

- 70°F day.

- °C = ((70°F-32) x 5/9).

- You should come out with 21.1°C.

-

Temperature Chart Example:

- Start at your initial temperature on the Fahrenheit scale.

- Move across until you hit the reference line.

- Move down and read the temperature off of the bottom.

- In this example it comes out to be roughly 22°C.

-

Temperature Conversion Table Example:

- Find the initial temperature and read across the column.

- Notice this table is more designed for Celsius to Fahrenheit but we still come out just over 21°C.

-

Pressure

- Atmospheric pressure is the force per unit area exerted against a surface by the weight of the air above that surface

- Put another way, pressure is the average force exerted over a given area by a fluid

- Standard pressure is 14.7 PSI or 29.92 in-Hg or 1013.2 mb

- The U.S. standard is in-Hg while most of the world uses mb

- To convert to in-Hg, divide mb by 33.86

- Temperature and pressure vary directly

- As altitude increases, pressure will decrease and by 18,000' the pressure has decreased by about half

- ISA: International Standard Atmosphere

- Air density is a result of the relationship between temperature and pressure

- Air density is inversely related to temperature and directly related to pressure

- For a constant pressure to be maintained as temperature increases, density must decrease, and vice versa

- For a constant temperature to be maintained as pressure increases, density must increase, and vice versa

-

High Pressure Systems:

- A mass of air that is considered more dense than the air around it

- Generally brings fair weather

- High pressure means sinking weather, so little cloud formation and turbulence

- Winds blow in a clockwise direction, therefore initially bringing weather conditions influenced by what is to its north

- This includes cooler temperatures, strong winds (turbulence) and lower humidity

- After passage, weather conditions are influenced by what is to the south

- This includes moist, warm air

- This may come in the form of a warm front and follow-on low-pressure system

- Low Pressure:

- A mass of air that is considered less dense than the air around it

- Generally brings bad whether

- Generally brings warmer temperatures and higher humidity

- Because air is less dense at higher altitudes, it causes:

- Wings to produce less lift

- Propellers to create less thrust

- Engines to create less power

Pressure Gradient Force

- Horizontal spacing of isobars affecting wind

Coriolis Effect

- Once air has been set in motion by the pressure gradient force, it undergoes an apparent deflection from its path as seen by an observer on Earth

- Accounts for the Earths rotation in the movement of air

- Acts 90° to the right of the wind in the northern hemisphere

- Coriolis force only affects direction, not speed

- Coriolis force depends on wind speed in that the faster the air is blowing, the more it is deflected

- Changes in latitude affect Coriolis force

- Coriolis force is zero at the equator and greatest at the poles

- Changes in altitude affect Coriolis force

- Below 2,000' friction disrupts the Coriolis force

- Geostrophic Balance:

- Pressure gradient force and Coriolis force general cancel each other out

- As a result, winds generally flow parallel to isobars

- Pressure always moves from high to low but in the northern hemisphere this will produce a right deflection of the air while the opposite is true in the southern hemisphere

Bay's Ballots Law

- The 4Hs have a negative effect on performance:

- Hot

- Heavy

- Humid

- High

Heat Vs. Temperature

- Heat: bouncing molecules

- Temperature: vibrating molecules

Turbulence

- Aircraft experience turbulence due to the irregular motion of an aircraft in flight as caused by various environmental conditionsis irregular motion of an aircraft in flight

- Worse the faster you go

- Most dangerous weather phenomenon to aircraft, hail being second

Convection

- The circulation process by which cool dense air replaces warm light air

- Air at the poles is cool and dense, and "sinks" toward the equator to replace warmer air

- The warmer air at the poles expands and rises, to move toward the poles

- This system created a general circulation pattern

- As the earth rotates, the general circulation pattern gives way to the three cell circulation pattern, and pressure systems

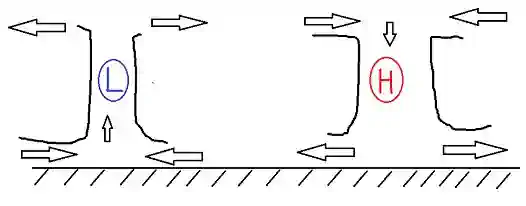

Pressure Systems

- An area of low pressure occurs when you have a convergence of air at the surface with a divergence of air aloft

- An area of high pressure occurs when you have a divergence of air at the surface with a convergence of air aloft

- In the general circulation pattern, high pressure dominates the poles, with low pressure at the equator

- Atmospheric pressure decreases more rapidly in cold air than warm air

- Temperature errors are smaller at sea level but increases with increased altitude

- High Pressure:

- Air flows clockwise, outward, and descends

- Winds therefore flow from the north/northwest, bringing with them colder temperatures, lower dew points, lower humidity, strong winds, and likely some turbulence

- Descending air warms and radiates outward

- Descending air can trap haze, smoke, and create temperature inversions

- High pressure is general associated with good weather

- Low Pressure:

- Air flows counterclockwise, inward, and rises

- Rising air cools and radiates outward

- Low pressure is generally associated with poor weather

- Points of equal pressure called isobars

- These different pressures create a pressure gradient, which is the source of wind

- Closely spaced isobars represent a strong gradient where the wind speeds will be higher than widely spread isobars

- Generally, air flows from high pressure areas to low pressure areas

- The rising air of a low leaves a void filled by the descending air of the high

Winds

- Pressure Gradient Force:

- The change in pressure measured across a given distance

- Air will travel from high to low because of PGF

- Resultant of the spacing of isobars

- Responsible for triggering the initial movement of air

- Coriolis Force:

- Described above

- Centrifugal Force:

- Its influenced upon the wind is dependent upon the linear velocity of the air particles and the radius of the curvature of the path of the air particles

- Winds produced by a combination of the pressure gradient force, Coriolis force, and centrifugal force flow parallel to the curved isobars

- Geostrophic Wind: When wind is blowing parallel to the isobars

- Gradient Wind: Wind blowing across isobars because the effects of PGF and Coriolis force cancel each other out when there is no frictional drag with the surface

- Surface Wind: Friction reduces the surface wind speed to about 40% of the velocity of the gradient wind and so it causes t he surface wind to flow across the isobars instead of parallel to them

- Jet Stream: Relatively strong wind concentrated within a narrow stream in the atmosphere, typically embedded in the mid-latitude westerlies' and is concentrated in the upper trophosphere

- Sea & Land Breezes:

- The difference in the specific heat of land and water causes land surface to warm and cool more rapidly than water surfaces through isolation and terrestrial radiation

- Therefore land is normally warmer than the ocean during the day and cooler at night

- Sea Breeze:

- During the day the pressure over the warm land becomes lower than over the cooler water

- The cool air over the water moves toward the lower pressure, replacing the warm air over the land that moved upward

- Land Breeze:

- At night, the pressure over the cooler land becomes higher than over the warmer water

- The cool air over the land moves toward the lower pressure, replacing the warm air over the water that moved upward

- Valley & Mountain Breezes:

- On warm days, winds tend to ascend the slopes during the day and descend the slopes at night

- Valley Breeze:

- In the daytime, mountain slopes are heated by the sun's radiation, and in turn, they heat the adjacent air through conduction

- This air usually becomes warmer than air farther away from the slope at the same altitude and, since warmer air is less dense, it begins to rise

- The air cools while moving away from the warm ground, increasing its density

- It then settles downward, toward the valley floor, which then forces the warmer air that is near the ground up the mountain again

- Mountain Breezes:

- At night, the air in contact with the mountain slope is cooled by outgoing terrestrial radiation and becomes more dense than the surrounding air

- The denser air flows down, from the top of the mountain, which is a circulation opposite to the daytime pattern

- Convective Currents:

- Uneven heating of the air creates a small area of local circulation called a convective current

- Caused by variations in surface heating

- Some surfaces give off heat (plowed ground, pavement)

- Some surfaces absorb heat (water, trees)

- Convective currents are most likely to be felt in areas containing a land mass directly adjacent to a large body of water, at low altitudes, and on warm days

- Obstructions:

- Structures, mountains or canyons can cause wind to rapidly change direction and speed

- Across mountains, air flows up the windward side and on the leeward side becomes turbulent

Frictional Force

- Caused by features on the Earth's surface

- Will be more pronounced over mountainous terrain than over the ocean

- Affects wind up to 2,000' above the surface

- Slows wind speed reducing Coriolis force, but not PGF

- As a result, surface winds tend to flow perpendicular to the isobars

Air Stability

- Air stability is the atmosphere's resistance to vertical motion

- Stability is the primary determinant of cloud development

- 5 primary causes of vertical lifting:

- Convergence: a net inflow of air usually associated with a low

- Divergence: a net outflow of air usually associated with a high

- Orographic: where air is forced up or down by terrain features

- Fronts: act like orographic lifting by forcing air up/down the front

- Convective: if air is warmer than its surroundings, it will rise until reaching an equilibrium temperature

- Vertical motion of air causes pressure changes within the parcel of air that is moving

- As air rises, it expands and cools

- As air sinks, it compresses and warms

- Pressure changes are accompanied by temperature changes

- Temperature changes (expansion/cooling - compression/warming) are called dry adiabatic processes

- Adiabatic cooling always accompanies upward motion

- Adiabatic heating always accompanies downward motion

- The rate at which temperature changes with respect to altitude is called lapse rate

- Temperature changes (expansion/cooling - compression/warming) are called dry adiabatic processes

-

Stable Air:

- Limits vertical motion

- Usually has smoother air, less cloud development

- Visibility is usually restricted by smoke/fog/haze

- Sinking air tends to have a stabilizing effect

-

Unstable Air:

- Encourages vertical motion

- Usually has turbulent air, with significant cloud development

- Visibility is usually good

- Rising air tends to have a destabilizing effect

Water Vapor

- 3 states of water: vapor, liquid, gas

- Each change of state requires an absorption or release of heat called latent heat

Humidity

- The amount of moisture present in the air is called humidity

- Relative humidity is the actual amount of moisture in the air compared to the total that could be present at that temperature

- Saturation is the point at which air holds the maximum amount of water it can

- Since water vapor weighs less than normal air, it can displace air and decrease density which increases density altitude

- Humidity Rule of Thumb: When ambient temperature is over 70°F, density altitude increases 100' for every 10% of humidity

Dew Point

- Defined as the temperature to which air would have to be cooled (with no change in air pressure or moisture content) for saturation to occur

- The difference between the temperature and dew point is called the temperature dew point spread

- When the spread is small, relative humidity is high and precipitation is likely

- As temperature decreases, air's ability to hold water vapor also decreases

Precipitation

- Defined as any form of water particles that fall from the atmosphere that reach the ground

- Can reduce visibility, decrease engine performance, decrease aerodynamic performance (rough airflow, increase drag) increase braking distance and cause significant shifts in wind direction and velocity (shear)

- Also, precipitation can freeze (ice), which is dangerous

- Causes:

- Water/ice particles too large for atmosphere to support

- Coalescence: when larger water droplets overtake and absorb smaller ones

- Ice-crystal process: using super-cooled water droplets to form larger heavy water partial in a relatively short time

Wake Vortex

- Anytime an airplane produces lift

- Most prevalent when aircraft is heavy, clean, and slow

- Engine blast is a realistic threat when taxiing behind/near large aircraft

- Takeoff and Landing Precautions must be exercised

Wind Shear

- A sudden drastic change in wind speed and direction that can occur vertically/horizontally at any level in the atmosphere

- Can be associated with convection, fronts, temperature inversions, etc.

Microburst

- More information can be found on the microbursts page

- A small localized downdraft less than 2.5 miles across

- Wind peaks of 170 mph possible

- Seldom last longer than 15 minutes

- Present severe landing dangers

- The Low-Level Wind Shear and Microburst Detection System (LLWAS) was developed to warn of wind shear conditions

Private Pilot (Airplane) Weather Information Airman Certification Standards

- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with weather information for a flight under VFR

- References: 14 CFR part 91; AC 91-92; AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8033-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge), FAA-H-8083-28 (Aviation Weather Handbook).

- Note: If K2 is selected, the evaluator must assess the applicant’s knowledge of at least three sub-elements.

- Note: If K3 is selected, the evaluator must assess the applicant’s knowledge of at least three sub-elements.

- Private Pilot (Airplane) Weather Information Lesson Plan

Private Pilot (Airplane) Weather Information Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

PA.I.C.K1:

Sources of weather data (e.g., National Weather Service, Flight Service) for flight planning purposes. -

PA.I.C.K2:

Acceptable weather products and resources required for preflight planning, current and forecast weather for departure, en route, and arrival phases of flight such as:.-

PA.I.C.K2a:

Airport Observations (METAR and SPECI) and Pilot Observations (PIREP). -

PA.I.C.K2b:

Surface Analysis Chart,, Ceiling and Visibility Chart (CVA). -

PA.I.C.K2c:

Terminal Aerodrome Forecasts (TAF). -

PA.I.C.K2d:

Graphical Forecasts for Aviation (GFA). -

PA.I.C.K2e:

Wind and Temperature Aloft Forecast (FB). -

PA.I.C.K2f:

Convective Outlook (AC). -

PA.I.C.K2g:

Inflight Aviation Weather Advisories including Airmen's Meteorological Information (AIRMET), Significant Meteorological Information (SIGMET), and Convective SIGMET.

-

-

PA.I.C.K3:

Meteorology applicable to the departure, en route, alternate, and destination under visual flight rules (VFR) in Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC), including expected climate and hazardous conditions such as:-

PA.I.C.K3a:

Atmospheric composition and stability. -

PA.I.C.K3b:

Wind (e.g., crosswind, tailwind, windshear, mountain wave, etc.). -

PA.I.C.K3c:

Temperature and heat exchange. -

PA.I.C.K3d:

Moisture/precipitation. -

PA.I.C.K3e:

Weather system formation, including air masses and fronts. -

PA.I.C.K3f:

Clouds. -

PA.I.C.K3g:

Turbulence. -

PA.I.C.K3h:

Thunderstorms and microbursts. -

PA.I.C.K3i:

Icing and freezing level information. -

PA.I.C.K3j:

Fog/mist. -

PA.I.C.K3k:

Frost. -

PA.I.C.K3l:

Obstructions to visibility (e.g., smoke, haze, volcanic ash, etc.).

-

-

PA.I.C.K4:

Flight deck displays of digital weather and aeronautical information.

Private Pilot (Airplane) Weather Information Risk Management:

The applicant is able to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with:-

PA.I.C.R1:

Making the go/no-go and continue/divert decisions, including:-

PA.I.C.R1a:

Circumstances that would make diversion prudent. -

PA.I.C.R1b:

Personal weather minimums. -

PA.I.C.R1c:

Hazardous weather conditions to include known or forecast icing or turbulence aloft.

-

-

PA.I.C.R2:

Use and limitations of:-

PA.I.C.R2a:

Installed onboard weather equipment. -

PA.I.C.R2b:

Aviation weather reports and forecasts. -

PA.I.C.R2c:

Inflight weather resources.

-

Private Pilot (Airplane) Weather Information Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

PA.I.C.S1 :

Use available aviation weather resources to obtain an adequate weather briefing. -

PA.I.C.S2:

Analyze the implications of at least three of the conditions listed in K3a through K3l, using actual weather or weather conditions provided by the evaluator. -

PA.I.C.S3:

Correlate weather information to make a go/no-go decision.

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Weather Information Airman Certification Standards

- Objective: To determine whether the applicant exhibits satisfactory knowledge, risk management, and skills associated with weather information for a flight under VFR

- Note: If K2 is selected, the evaluator must assess the applicant’s knowledge of at least three sub-elements.

- Note: If K3 is selected, the evaluator must assess the applicant’s knowledge of at least three sub-elements.

- References: 14 CFR part 91; AC 91-92; AIM; FAA-H-8083-2 (Risk Management Handbook), FAA-H-8083-3 (Airplane Flying Handbook), FAA-H-8033-25 (Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge), FAA-H-8083-28 (Aviation Weather Handbook).

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Weather Information Knowledge:

The applicant demonstrates an understanding of:-

CA.I.C.K1:

Sources of weather data (e.g., National Weather Service, Flight Service) for flight planning purposes. -

CA.I.C.K2:

Acceptable weather products and resources required for preflight planning, current and forecast weather for departure, en route, and arrival phases of flight such as:-

CA.I.C.K2a:

Airport Observations (METAR and SPECI) and Pilot Observations (PIREP). -

CA.I.C.K2b:

Surface Analysis Chart,, Ceiling and Visibility Chart (CVA). -

CA.I.C.K2c:

Terminal Aerodrome Forecasts (TAF). -

CA.I.C.K2d:

Graphical Forecasts for Aviation (GFA). -

CA.I.C.K2e:

Wind and Temperature Aloft Forecast (FB). -

CA.I.C.K2f:

Convective Outlook (AC). -

CA.I.C.K2g:

Inflight Aviation Weather Advisories including Airmen's Meteorological Information (AIRMET), Significant Meteorological Information (SIGMET), and Convective SIGMET.

-

-

CA.I.C.K3:

Meteorology applicable to the departure, en route, alternate, and destination under visual flight rules (VFR) in Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC), including expected climate and hazardous conditions such as:-

CA.I.C.K2a:

Atmospheric composition and stability. -

CA.I.C.K2b:

Wind (e.g., windshear, mountain wave, factors affecting wind, etc.). -

CA.I.C.K2c:

Temperature and heat exchange. -

CA.I.C.K2d:

Moisture/precipitation. -

CA.I.C.K2e:

Weather system formation, including air masses and fronts. -

CA.I.C.K2f:

Clouds. -

CA.I.C.K2g:

Turbulence. -

CA.I.C.K2h:

Thunderstorms and microbursts. -

CA.I.C.K2i:

Icing and freezing level information. -

CA.I.C.K2j:

Fog/mist. -

CA.I.C.K2k:

Frost. -

CA.I.C.K2l:

Obstructions to visibility (e.g., smoke, haze, volcanic ash, etc.).

-

-

CA.I.C.K4:

Flight deck instrument displays of digital weather and aeronautical information.

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Weather Information Risk Management:

The applicant is able to identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with:-

CA.I.C.R1:

Making the go/no-go and continue/divert decisions, including:-

CA.I.C.R1a:

Circumstances that would make diversion prudent. -

CA.I.C.R1b:

Personal weather minimums. -

CA.I.C.R1c:

Hazardous weather conditions, including known or forecast icing or turbulence aloft.

-

-

CA.I.C.R2:

Use and limitations of:-

CA.I.C.R2a:

Installed onboard weather equipment. -

CA.I.C.R2b:

Aviation weather reports and forecasts. -

CA.I.C.R2c:

Inflight weather resources.

-

Commercial Pilot (Airplane) Weather Information Skills:

The applicant exhibits the skills to:-

CA.I.C.S1:

Use available aviation weather resources to obtain an adequate weather briefing. -

CA.I.C.S2:

Analyze the implications of at least three of the conditions listed in K3a through K3l, using actual weather or weather conditions provided by the evaluator. -

CA.I.C.S3:

Correlate weather information to make a go/no-go decision.

Atmosphere Conclusion

- For more information, a paper copy of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA-H-8083-28) Aviation Weather Handbook [Amazon] is available for purchase

- A digital copy of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA-H-8083-28) Aviation Weather Handbook is available from the FAA's website

- Looking for more? Check out the AOPA's Aircraft Owners and Pilot's Association - Weather Wise: Air Masses and Fronts

- Improve your weather skills with FAA provided (and WINGS credited) resources by going to https://www.faasafety.gov/ and type "weather" into the search bar

- Still looking for something? Continue searching: